The hardest job at any chip designer that doesn’t actually own its own foundry – and maybe even those that do – is figuring out what wafer start commitment level to make for a new compute engine in the datacenter. Guess too low, and you are supply constrained. Guess too high, and you end up with far too many chips and that results in lower profits and inventory on the books.

We have been pondering the competitive situation between Intel and its “Cascade Lake” Xeon SP generation of server processors and AMD and its “Rome” Epyc alternatives, and it is not so much that we were ever surprised that AMD could reach double-digit shipment market share, as was the stake that AMD president and chief executive officer Lisa Su drove into the ground as it returned to the datacenter three years ago. Rather, it is that given all of the difficulties that Intel has had with its 10 nanometer manufacturing processes, which are now six years late on the server, and now the slip with its 7 nanometer processes (which affects Intel’s Xe GPU accelerator lineup next year more than it does the server lineup, which would not be on 10 nanometer processes until the shrink to 7 nanometer in 2022 according to the N-1 iteration of “the current plan”), how AMD’s share is not already at 15 percent – or even higher.

The first 10 percent or so of market share took three years, coming off basically zero before the launch of the “Naples” Epyc chips. And we keep wondering if it will take half as long to get the next 10 percent, which is normal for a lot of markets with an aggressive competitor, or about the same time, which sometimes happens, or a very long time or maybe it never happens because Intel can keep making arguments to server makers and server buyers that convinces them to stay within the Xeon SP fold.

We think there is a combination of factors at work that make it both easy and tough for AMD to grow its share of the $79 billion total addressable market that it is chasing with its consumer and corporate compute engines. But here, we are focused on the datacenter and to a certain extent of the edge, but we never lose sight of the fact that the initial re-entry into the server market with Epyc was very much predicated on what was happening with Ryzen desktop chips based on the same Zen 1 and Zen 2 cores.

Based on statements that AMD’s top brass made when discussing the company’s second quarter 2020 financial results, we strongly suspect that demand for AMD’s Epyc server chips is outstripping supply, and furthermore we believe that the supply constraint is really a function of how much demand there is for the 7 nanometer manufacturing processes at foundry partner Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. You know, TSMC, the only chip maker that is shipping 7 nanometer processes for datacenter compute engines; TSMC, the company that at this point defines what is possible in the datacenter until Intel and Samsung get their 7 nanometer technologies to market possibly around the same time late next year. (Samsung is making IBM’s Power10 processors, as we talked about in December 2018, after GlobalFoundries spiked its own 7 nanometer extreme ultraviolet wafer etching efforts back in August 2018.) We got a whole lot of compute eggs in one basket in Taiwan, and that is a risk that is getting unpalatable to a lot of companies and countries dependent on compute technology evolving at a steady clip.

AMD launched the “Naples” Epyc 7001 family of server chips back in June 2017, and these were based on a chiplet architecture that put four eight-core chiplets, etched in 14 nanometer processes from GlobalFoundries, in a socket and glued them together into a virtual die using PCI-Express links and the Infinity Fabric protocol. A year later, AMD was telling the world that it was coiled to spring over Intel, jumping from 14 nanometer chips straight to 7 nanometer devices with the Rome Epyc chips. It turned out to be a bit more complicated than that. With the Rome Epyc 7002 processors launched in August 2019, the I/O and memory controllers were extracted and conglomerated onto a 14 nanometer chiplet from GlobalFoundries, and then eight blocks of two four-core CPU complexes were etched using TSMC’s 7 nanometer processes – we drilled down into the details here in what we thought was a pretty good analysis of the extreme co-design we expect in future compute engines of all styles.

Given that TSMC is basically the advanced foundry for the world, and AMD needs to sell chips for laptops, consoles, and servers, and that its margins appear to be better on desktop chips, it has to be hard to do the juggling act across the Ryzen and Epyc CPUs, the “Navi” and “Big Navi” GPUs, and the custom Microsoft and Sony game console chips. That’s six chips to push through a tight set of 7 nanometer foundries that are in high demand among the chipmakers of the world who are etching network switch, router, and interface ASICs, CPUs, GPUs, and custom AI compute engines.

Su spoke generally about the interplay of supply and demand, not specifically singling out either desktop or server CPUs or desktop, laptop, or server GPUs.

“We have a strong supply chain,” Su explained on the call, talking about the supply/demand balance and the fact that AMD has raised its revenue guidance for the third quarter and the full 2020 year. “There is no question that it has been a very dynamic year if you just think about all the puts and takes over the last four or five months. I have said it before and I will say it again, 7 nanometer is tight and we continue to partner closely with TSMC to ensure that we can satisfy our customer demand. When you ask about the full year raise, it is because demand has gone up from our initial expectations, but some of that is due to the market and some of that is due to the strength of our product traction. We are increasing capacity to meet those needs, but it is tight and I would say that as we continue to increase capacity, we see opportunity there. So from that standpoint, demand is strong.”

It is important to recall that AMD got burned badly during the Opteron era and beyond in the Great Recession as demand dropped off just as a resurgent Intel launched an Opteron-alike “Nehalem” Xeon E5500 processor and AMD had to renegotiate its wafer supply agreements with GlobalFoundries – its own spun-off foundry, mind you – to its short-term financial detriment. So AMD is probably a little gun shy about overcommitting in its production schedule. But any nervousness has to be balanced against the fact that hyperscalers and cloud builders need to buy products in lots of 50,000 or 100,000 and they want a steady supply. Intel can guarantee that with its very, very mature 14 nanometer process, which arguably should be called 14+++++++++ at this point because it has been refined so many times. And there are lessons to be learned here. If TSMC’s 7 nanometer processes are supply constrained, what would have happened if AMD had a plan to do hybrid chiplets in GlobalFoundries 14 nanometer processes for both the core chiplets and the I/O and memory hub, with maybe only 8 or 12 cores in the socket but maybe the same number of memory and I/O controllers, creating a bandwidth beast? Could it have put an even cheaper chip in the field to go after the belly of the Xeon SP market? Or create a new class of chips for new use cases?

Many of us on the call walked away with the impression that AMD was supply constrained to a certain extent for Epyc CPUs, but also that AMD was working with TSMC to inch capacity up to meet growing demand as more platforms from more OEMs and ODMs and more instances from cloud builders deploy Epyc. There is steady and rising demand for Epyc in the HPC sector as well, but that business will take years to build. Ditto for the datacenter GPU business, which was down in the quarter but which Su said would grow in the second half of the year just like the Epyc CPU business is expected to grow. (But not at the same rates, of course.) The mindshare of the Radeon Instinct GPU accelerators is rising, no doubt thanks to promised about the future iterations of the ROCm hybrid CPU-GPU development environment and to AMD capturing the future “Frontier” and “El Capitan” exascale systems for both CPUs and GPUs at the US Department of Energy – specifically at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

If we were Intel facing intense competition from AMD in the X86 server arena, we would have probably promised very good deals on future 10 nanometer “Ice Lake” and “Sapphire Rapids” Xeon SP processors to high volume customers who would buy current 14 nanometer “Cascade Lake” processors today – probably also at steeper discounts but also at higher ASPs with more clocks and more cores for any given slot in the SKU stack. We also suspect that Intel us being generous with the MDF marketing cash to those OEM customers who are emphasizing Xeon SP processors. These are other reasons why AMD’s shipment market share in server CPUs is not higher given all of the dynamics. The 7 nanometer shift doesn’t hurt the near-term Ice Lake and Sapphire Rapids chips, but it does hurt the “Granite Rapids” chips that were expected at the end of 2022 and now are pushed into early 2023.

It is hard to say how annoyed hyperscalers and cloud builders will be about that delay. And it is also hard to say if TSMC will be able to keep stepping down through the process nodes as flawlessly – and as impressively – as it has been able to do.

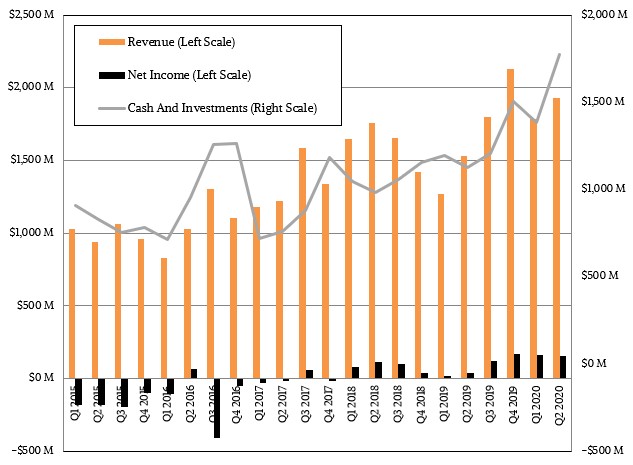

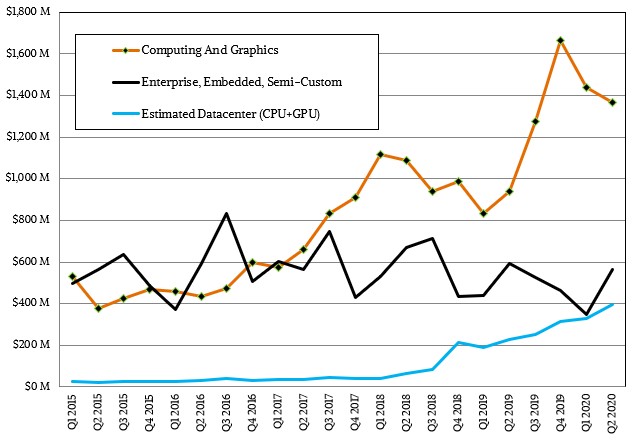

In the second quarter ended in June, AMD posted sales of $1.93 billion, up 26.2 percent. Net income was essentially flat sequentially but was up by a factor of 4.5X against a very weak Q2 2019. The company exited the quarter with $1.78 billion in cash and equivalents in the bank.

Sales in the Computing and Graphics group rose by 45.4 percent to $1.37 billion, and operating income rose by a factor of 9.1X to $200 million. And Su said that AMD had been anticipating that the PC business would be down in the second half of this year and now expects it to be up. The third generation “Milan” Epyc processor “is looking good,” according to Su, and will be shipping towards the end of the year, as will be the “Big Navi” kicker in the Radeon GPU and Radeon Instinct GPU accelerator lines, and AMD is anticipating that the datacenter business will be up in 2H 2020 versus 2H 2019. But, in the second quarter, the datacenter GPU business was down, but the drop was more than offset by the increase in Epyc CPU sales.

AMD said that the datacenter chips accounted for more than 20 percent of revenue – our model puts it at 20.5 percent – and if you do that math, that works out to $396 million in datacenter business for AMD, up 19.9 percent sequentially from Q1 2020 and up 72.5 percent from the year ago period. Epyc CPU sales rose by 32.3 percent to $334 million in our model, and Radeon Instinct GPU accelerator sales fell by 20.5 percent to $62 million in the quarter.

In the trailing twelve months, Epyc CPU sales were just over $1 billion and the annualized run rate in Q2 came to $1.34 billion. The datacenter GPU business had trailing twelve month sales of $265 million, and the goal that AMD has stated in the past is that this business would consistently have $500 million in revenues per year – and that this would happen in the next few years. Given Nvidia’s dominance in GPU compute and Intel coming into the picture next year, this might be a practical goal, but we think there is potential for AMD to do better in both CPUs and GPUs. A lot depends on what the other players in datacenter compute do – and fail to do.

Be the first to comment