We have a long-standing joke that dates from the early 2000s, when the hyperscalers – there were not yet cloud builders as we now know them – started having hundreds of millions of users and millions of servers and storage arrays to run applications for them at the same time there was the beginnings of consolidation among the OEMs who created the servers and storage used by nearly all enterprises, including dot-com startups.

Here it is: “We used to worry about a world where there might only be five sellers of servers and storage. Now, we worry that there might only be five buyers of servers and storage.”

Just as the coronavirus pandemic kicked in during the first quarter of 2020, according to data from IDC that we have been tracking like a hawk since it was first released in 2021 in its Worldwide Quarterly Enterprise Infrastructure Tracker, service providers – meaning hyperscalers, cloud builders, and other service providers who build datacenter infrastructure and sell capacity on it – as a group surpassed 50 percent share of combined server and storage revenues on Earth. They had accounted for more than half of unit shipments several years earlier, by our estimates.

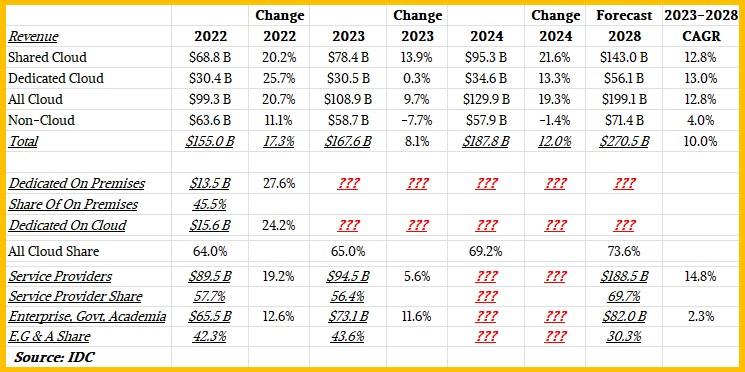

If the prognosticators at IDC are correct, four years from now as 2028 is coming to a close, the service providers as a group will comprise more than two thirds of server and storage revenues for that year. The latest forecast for 2028, in fact, shows the service providers, who bought $94.5 billion in server and storage equipment in 2023 – up 5.6 percent and giving the SPs a 56.4 percent share – will see their spending rise to $188.5 billion by 2028, giving this prestigious group 69.7 percent share of money spent on this gear. Enterprises, governments, and academic institutions accounted for $73.1 billion in server and storage acquisitions last year, up a much healthier 11.6 percent year on year and giving them a 43.6 percent share of spending. But by 2028, with a compound annual growth rate that is 6.4X as small at 2.3 percent, this EG&A share will fall to 30.3 percent of spending and will only hit $82 billion by 2028.

That is more like dozens of server buyers in that majority slice, but it is a lot closer to five server buyers than we would like. And we wonder how the remaining server OEMs who serve the EG&A class of customers are going to grow and stay financially healthy. Or in some cases, get financially healthy in the first place.

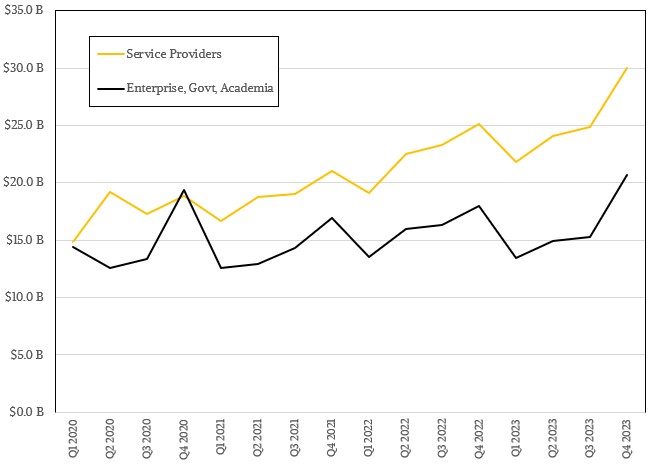

Here is what sales of servers and storage to the SPs versus the EG&As looks like over the past four years, which is the only data we have available from IDC for these two distinctions:

The gap between the two classes of server and storage buyers does not look all that big, does it? But it has been inching up, on average, over the past two and a half decades, and it looks to us like AI servers running large language models is going to tip the balance starting in 2024. IDC did not explain the massive difference in growth rates in its public report, but we think this is the differentiator. And it might just turn out that LLMs are the killer apps for clouds, compel enterprises, governments, and academic institutions to do it on the cloud rather than fight for budget and accelerators for their own datacenters.

Growth for SPs and EG&As is choppy. Neither is particularly linear on a quarterly basis. But there will be a bigger gap opening up if IDC is right.

This data is presented by IDC as a way of explaining sales of machinery for cloudy infrastructure, as distinct from bare metal machines that run relational databases and suites of ERP, SCM, CRM, and other back office applications. (Those are abbreviations for enterprise resource planning, supply chain management, and customer relationship management, and they are the major things that most enterprises do, which includes boring stuff like accounts payable and receivable and payroll. We think payroll is very exciting, personally. . . .)

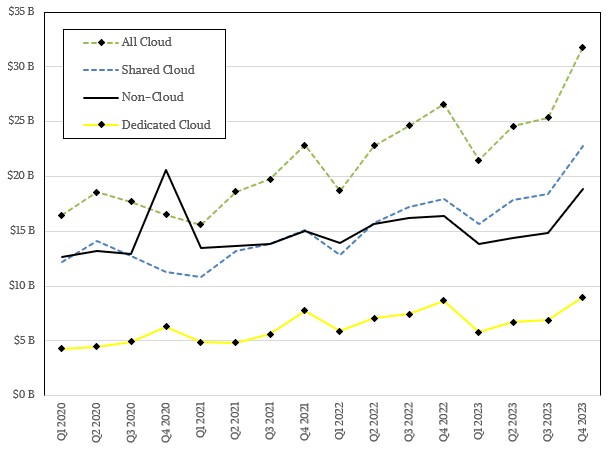

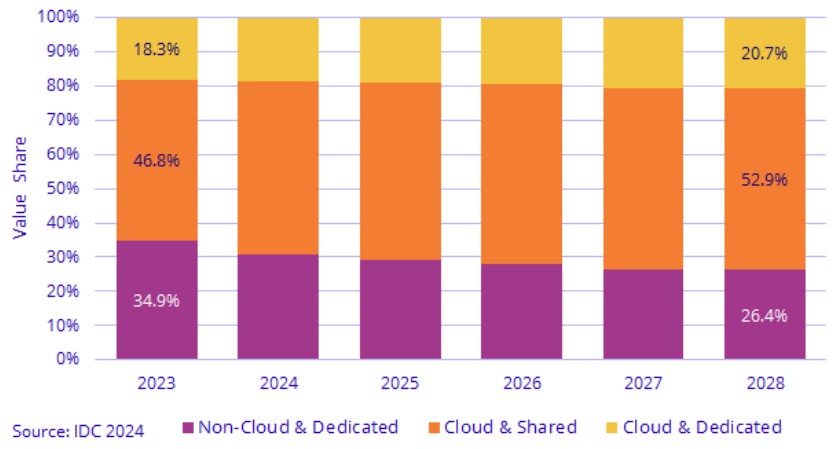

Here is how that spending looked for the past several years for shared cloud, dedicated cloud, and non-cloud uses:

Shared cloud infrastructure is just what it sounds like: Machines sold so they can be virtualized and sold with multiple companies concurrently renting time on them. Dedicated cloud means machines are sold to be used as host machines in the more traditional outsourcing sense – one box, one customer – as well as outpost infrastructure sold under a cloud pricing model for companies to run in their datacenter or in a co-location facility of their choosing. Non-cloud is that boring back office stuff that keeps the global economy actually spinning.

In the past, IDC broke the apart the dedicated cloud market into dedicated on the cloud and dedicated on premises, and we are pretty sure it still does this but it is no longer doing this in the data it releases to the public.

Here is a monster table that brings all we know of the IDC covering 2022 and 2023, also includes the forecast for 2024 and the one way out into 2028:

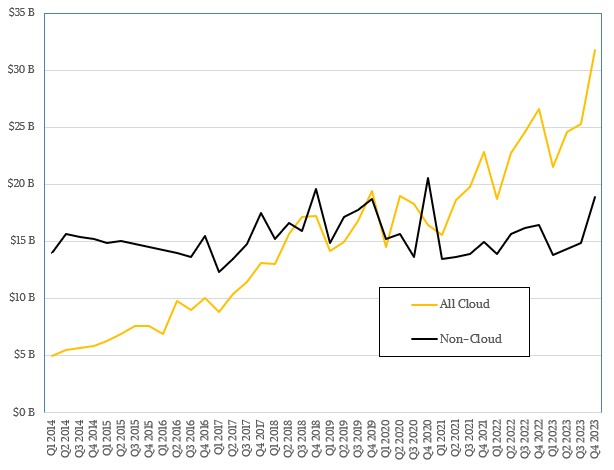

For those of you who think visually, here is a chart of cloud versus non-cloud server and storage buying since 2014, which is part of an older and larger dataset we have been watching, before it broke out the different types of cloud spending and before it started giving the SP and EG&A breakout. Take a gander:

And here is the breakdown of the different kinds of cloud versus non-cloud spending:

And, to complete the set, here is a stacked bar chart that shows the breakdown in spending across the three types of customer use cases – non-cloud, shared cloud, and dedicated cloud – between 2023 and 2028:

Nearly two decades ago, when the second wave of utility computing started – remember the rise of application service providers and grid computing in the wake of the commercialization of Internet technologies in the late 1990s? – it was important to monitor the rise of the cloud computing consumption model. But in the end, cloud is just a consumption model. What we talked about at the top of this story is a change in the consumers themselves, and this is perhaps more profound in the long run.

In that longest of runs, enterprises may lose the skillsets required to run their own infrastructure as they become more dependent on service providers. In that longest of runs, there may not be independent chip makers and system makers and storage makers, and IT may get a hell of a lot more expensive because of that. There may not be any server buyers at all, and no server makers. Just hyperscale clouds (that is an intentional hybrid) that sell application access with expensive AI built in that no one can easily replicate in a datacenter of their own, all based on hardware of their own design and making.

What if the plan for the hyperscalers and cloud builders is not just to build their own stuff, but to keep you and your OEM partners from building an alternative? That is what happens when the EG&A sector gets too small, and don’t think for a second these ever-hungry behemoths don’t know it.

Resist. Control your fate. Pay for it. Your future is yours, not theirs. Own it. Doing your own IT might cost you more, it might cost you less. But you are in charge of what you do — and what you don’t do — that way.

It’d sure be sad to see on-prem operations stepchild-ed, Hansel and Gretel-style, to some deep-moated gingerbread outfit in the woods that turns out to be a dungeon-kitchen run by a cannibalistic witch IMHO. In these wicked times of GPU famine, there can’t be rest for the weary and hungry (I think)! 8^b

Do you think this is how small farmers feel about Driscol and other “hyper-farmers?”

Absolutely.

Resistance is futile! Cloud services provide a utility service – like electricity. Unless you are doing something on very specialized hardware, the cloud services provide better services cheaper than the Enterprise can do themselves – any more than they would generate their own electricity at scale. The hardware and systems chosen at an infrastructure level do not differentiate how well an enterprise performs – there is no “value add” there. An Enterprise’s bottom line isn’t improved because of them running their own hardware and building their own underutilized datacenters. The Enterprises’ differentiation is in their applications and business model. As time goes on, the remaining “generic” stuff will be migrated to the cloud.