After two and a half quarters of tightening the purse strings, the world’s largest consumers of infrastructure – the eight major hyperscalers and cloud builders – plus their peers in the adjacent communications service provider space all started spending money on servers and storage again, and Intel can breathe a sigh of relief as it works to get its 10 nanometer manufacturing on track for the delivery of “Ice Lake” Xeon SP processors sometime in the second half of next year.

That five year delay in ramping 10 nanometer manufacturing on servers, you might think, would be a boon for AMD’s second generation “Rome” Epyc 7002 processors. While AMD’s market share is certainly growing in server processors, it has not gone from 0 percent to 10 percent share as Intel has struggled, which is what happened to AMD in reverse 2009 when Intel put the very well-regarded “Nehalem” Xeon E5500 processors into the field at exactly the same time its upstart server chip rival was struggling with Opteron designs and the Great Recession. Intel capitalized brilliantly and AMD was vanquished from the datacenter.

This time around, Intel is not being vanquished because of its delays and AMD is not seeing explosive growth so much as steadily building momentum, perhaps all that it is due given its utter abandonment of servers between say 2010 and 2017, when the first generation “Naples” Epyc chips were launched. In that short period of time, the entire market changed, with the hyperscalers, cloud builders, and comm service providers going from less than a fifth of Intel’s server CPU sales (as gauged by revenues, not shipments) to over two thirds of revenues in the current (and what is considered a normal) quarter.

With that much demand from the hyperscalers, cloud builders, and service providers, a secondary supplier like AMD cannot meet all of the demand– at least not yet – and as long as Intel can keep list prices high, discount like crazy for the hyperscalers and cloud builders, discount aggressively for the other service providers and the upper echelon HPC centers, and discount only modestly for the rest of the market – dominated by enterprises that are extremely risk averse and individually buying at orders of magnitude lower volumes – then the aggregate can still throw off a huge amount of cash.

Even with AMD competing intensely, there is enough share and growth to go around, particularly when AMD is just as supply constrained as Intel is, and CPUs from the Arm collective and Power9 from IBM are not nearly as easy to consume as an X86 server processor for most companies. If this were 2009, AMD would be cleaning Intel’s clocks. But it isn’t 2009. The world is different. AMD will get its share, and it may even get 10 percent or 20 percent shipment share for CPUs in servers. But it ain’t gonna happen overnight.

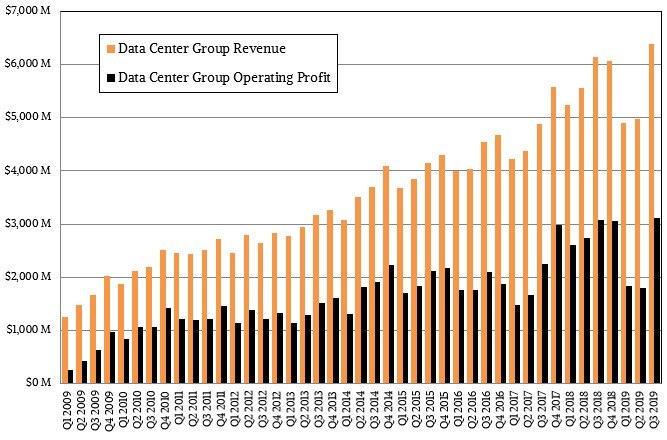

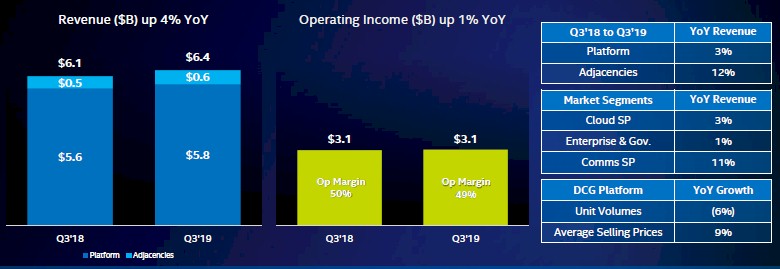

In the quarter ended in September, Intel’s Data Center Group had $5.82 billion in platform sales – meaning CPUs, chipsets, and motherboards. That was an increase of 3.2 percent compared to the prior’ year’s stellar third quarter, when the 2018 datacenter buildout was in full swing and the “Skylake” Xeon SP processors were ramping quickly. Data Center Group booked another $564 million in adjacent revenues – including things like Omni-Path networking, server adapter cards, and full systems – an increase of 12.4 percent. Add it up, Data Center Group posted $6.38 billion in sales, up 4 percent. Unit volumes for Data Center Group products fell by 6 percent in the quarter, but average selling prices, driven by customers moving up the SKU stack, rose by 9 percent, which is how Data Center Group grew.

Operating income for the group rose by only 1.1 percent, though, to $3.12 billion, which we think means the favorable mix of more expensive Xeon SP cores with more cores and features activated was mitigated in part by the competition with AMD from its Rome Epycs. There is no question that Intel is cutting prices to win business across all of its markets, and we think the price cuts are a bit steeper on average than the SKU upsell. The operating income is still hanging around 50 percent, which is as good as we think it can get for Intel and as much as anyone can expect.

Bob Swan, Intel’s chief executive officer, provided a little bit of color on Data Center Group in the call with Wall Street analysts to go over the figures for the third quarter of 2019. Swan said that in the nine quarters since the Skylake processors had launched, which were followed up by the “Cascade Lake” Xeon SPs in April, and that across both lines Intel had sold a cumulative 23 million units through the third quarter. Major cloud players Amazon Web Services, Alibaba, and Google got Cascade Lake instances on their clouds during this period, and the OEMs and ODMs are starting to move customers over to the newer chips as well, which offer a modest bump in bang for the buck.

The sales of server, storage, and networking chippery and boards to hyperscaler and cloud builder customers – what Intel calls Cloud SPs – rose by 3 percent year on year in the September quarter, and sales to communications service providers – what Intel calls Comms SPs – was up 11 percent, according to George Davis, Intel’s chief financial officer. Together, then, given what Swan said about the contribution that these two sectors make to Data Center Group sales, they accounted for about $4.3 billion in sales. Just for comparison’s sake, in the year ago quarter, Cloud SP sales were up a stunning 50 percent and Comms SP sales were up 30 percent. Enterprise and government sales were up a meager 1 percent, and that was great news a year ago. This time around, thanks in large part to sales pulled in from future quarters by the trade war with China, enterprise and government sector sales for Intel were again up 1 percent in Q3 2019. They probably would have been flat to down were it not for this bump, is our guess, and this was better than Intel had been expecting, in fact.

Intel doesn’t bundle all of its datacenter sales together into one line item in its books, even though it does distinguish its “data centric” business as distinct from the rest, like this:

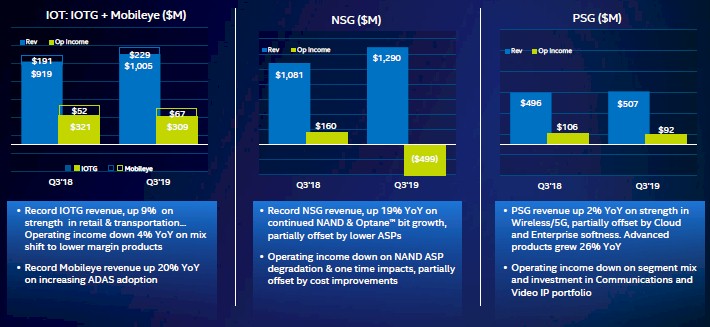

All of these businesses above have datacenter, client, and embedded customers. The Programmable Systems Group, which includes the Altera family of FPGAs, posted sales of $507 million, up 2.2 percent, and operating income was $92 million, down 13.2 percent. Part of the profit hit here was the ramping of the Agilex FPGA to 10 nanometer processes in the quarter.

Intel’s NAND flash and Optane PCM memory businesses together posted record sales of $1.29 billion, up 19.3 percent, but continue to bleed red ink as they have for the past four years. In the current quarter, Intel lost a staggering $499 million in this memory business, and if you add it up since the first quarter of 2016 through the third quarter of 2019, the Non-Volatile Storage Group has brought in $13.55 billion in revenues and $1.89 billion in losses. By comparison, Data Center Group has had $75.56 billion in sales and $34.15 billion in operating profits over the same time period. The latter is an epically good business and the former is a work in progress, in a cut-throat environment, that Intel is committed to for very good reasons. But it still hurts.

Another interesting tidbit that Swan shared, which was not qualified further, was that Intel expects to generate $3.5 billion in revenues from AI in 2019, which will be 20 percent higher than in 2018. This includes all kinds of AI chippery, from embedded devices to those running in the datacenter, from CPUs to FPGAs to specialized ASICs.

Looking ahead, Intel is raising its revenue guidance by $1.5 billion since it talked about Q2 2019 numbers in July, and now thinks it can grow modestly for the year to around $71 billion in sales, with data-centric sales flat to slightly up and PC-centric sales flat to slightly down. Intel expects that gross margins for the year will be down about 2 percent thanks to flash price cuts and the 10 nanometer manufacturing ramp. Intel is cutting $900 million in costs out of the rest of the business so it can plow another $500 million into investments in research, development, and capacity for the 10 nanometer and 7 nanometer manufacturing nodes. (This is akin to the 7 nanometer and 5 nanometer nodes at rival Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp.) Intel has added 25 percent wafer start capacity so far in 2019, some of it for 14 nanometer processes so it can meet PC and server CPU demand for existing products and some of it for the 10 nanometer ramp.

Speaking of that vital 10 nanometer ramp, Swan said that Intel had the process up and running in its fabs in Oregon and Israel and that it will soon fire it up in the Arizona fab. “Yields are improving ahead of expectations for both client and datacenter products,” Swan added, and rattled off the cadence of products that are based on its very much revised and delayed 10 nanometer process. The “Ice Lake” Core processors are out the door and ramping for holiday season PC sales, and of course the Agilex FPGA is now shipping based on 10 nanometers as well. Next year, 10 nanometer manufacturing will be applied to “Ice Lake” Xeon SP processors aimed at server, storage and networking jobs as well as to an AI inference accelerator – that would be the “Spring Hill” Nervana NNP-I, the companion to the “Spring Crest” Nervana NNP-T chip for machine learning training. The 10 nanometer manufacturing will also be used on the a special SoC for 5G base stations and on the first discrete Xe family GPU coming out of Intel, called DG1, which was powered up during the quarter in Intel’s labs. This is not a server, but a PC part, so don’t get too excited. Swan did say that the first product to use its 7 nanometer processes will be the server-class Xe discrete GPU in 2021, and we suspect that this device is the one that will be used in the future “Aurora” supercomputer at Argonne National Laboratory – the first exascale system in the United States.

The important thing for Swan is that the gap between the first 10 nanometer Agilex part here in 2019 and the 7 nanometer Xe discrete server GPU accelerator in 2021 is two years – the traditional Moore’s Law cadence. And the gap between 7 nanometer and 5 nanometer should be, as Intel has been telling Wall Street since May, somewhere between two years and two and a half years.

Intel believes so much in its roadmaps and its ability to execute on them that its board has authorized a $20 billion share buyback program. While this may make financial and opportunistic sense on the face of it, we generally don’t approve of such things. Intel’s shares are not under huge pressure and at $231 billion in market capitalization is close to double what it had three years ago. We think that $20 billion could be spent a lot more intelligently in bolstering Intel’s tarnished manufacturing operations, not in making Wall Street feel better about its stock picks. To put it bluntly, that is the cost of two new fabs.

The DCG YoY numbers did the talking:

1) Unit Volumes, -6%.

2) ASP, +9%.

3) Revenue, +4%.

Volume down + ASP & Revenue up = MILKing customers?

The only easiest zero-risk way to make up the performance loss caused by the security patches is buy more Xeon chips!