There is such a thing as a string of bad luck, but we have always believed that luck is the residue of design, either good or bad. And so it is hard not to lift a skeptical eyebrow pretty high, given the many-year delay in the rollout of 10 nanometer processes, at the news announced today that Intel is now going to stomach a six-month delay in rolling out its 7 nanometer CPUs and GPUs.

Ugh.

It is very difficult, even for the staunchest supporters of Intel, to not believe that something is truly awry with how the chip maker is managing its manufacturing process nodes.

The company, along with IBM and AMD/Globalfoundries, used to represent American prowess in chip making. In recent years, the true brilliance that Intel has shown is in squeezing every last drop out of its now ancient 14 nanometer FinFET techniques, which first made their debut in the datacenter with the “Broadwell” Xeon D chips in early 2015 followed by Xeon E5 chips in early 2016. Difficulties in ramping up the yields on the 14 nanometer processes on PC chips, which were used to gear up the fabs in those years, pushed out these server chip launches, so it is not like Intel was having an easy time initially with the 14 nanometer node. The situation got worse – a lot worse – with the 10 nanometer node, which is now six years late on the Xeon chips for servers compared to the original plan.

And yet, if aliens had come to Earth and looked at Intel’s financial results for the past three years against datacenter spending trends, when it had long since planned to have 10 nanometer processes in use on its Xeon SP processors – and without any prior knowledge of Intel – these aliens would have never guessed from these financials that the world’s largest chip maker in 2019 (after knocking Samsung Electronics, riding high on the memory and flash waves, down a peg after it surpassed Intel in 2017 and 2018) had even the merest hiccup in its manufacturing.

There would have been the ups and downs of the hyperscalers and cloud builders, to be sure, but Intel weathered these waves as well as any company could and managed to more than make up for it, plowing ahead. And continued to perform extremely well financially here in the second quarter, as we will show in a moment. But at some point – and that point might be right now – the Teflon has all but burnt off the pan and Intel’s top brass and its market share in the datacenter are going to start feeling the heat.

But certainly not in the second quarter of 2020, which was just stellar for Intel’s Data Center Group. And in some kind of twisted pretzel logic, delays with 14 nanometer, 10 nanometer, and now 7 nanometer products in the future have correlated rather strongly with very good growth for Data Center Group in the then-present. Intel might want to have a delay with 5 nanometer technologies and keep its revenue and profits growing for the next decade. . . . Yes, that was sarcasm.

This situation is unprecedented and counterintuitive, and it is a true testament to Intel’s ability to wheel and deal with the OEMs and ODMs of the world, cut prices, eat a little into profits, yield a tiny bit of market share, and still command a relatively high operating profit for its datacenter business. It is largely the difference between using a mature process with no kinks and using one with lots of kinks in it that makes this all work from a financial standpoint.

There’s a reason that Globalfoundries hung back with 14 nanometer and 12 nanometer processes and spiked its 7 nanometer efforts. It would not be surprising to see the two partner at some point in the future to take on the hegemony of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp to spread out the risks and the costs. That is a far more palatable option, both spiritually and politically, than Intel partnering with TSMC. It would also no be surprising to see Intel, Globalfoundries, and Samsung, partner and try to counterbalance TSMC and provide a hedge for the world. The IT industry has a lot of chip eggs in TSMC’s 7 nanometer and 5 nanometer baskets.

That brings us to the delay that Intel is having with its 7 nanometer process, which Bob Swan, Intel’s chief executive officer, talked about on the call with Wall Street analysts. Here is how Swan explained the situation, which we quote at length:

“We are seeing an approximate six month shift in our 7 nanometer CPU product timing relative to prior expectations. The primary driver is the yield of our 7 nanometer process, which based on recent data, is now trending approximately twelve months behind our internal target. We have identified a defect mode in our 7 nanometer process that resulted in yield degradation. We have root-caused the issue and believe there are no fundamental roadblocks, but we have also invested in contingency plans to hedge against further schedule uncertainty. We are mitigating the impact of the process delay on our product schedules by leveraging improvements in design methodology, such as die disaggregation and advanced packaging. We have learned from the challenges in our 10 nanometer transition and have a milestone-driven approach to ensure our product competitiveness is not impacted by our process technology roadmap. Our overarching priority is to deliver product leadership for our customers, and we are taking the right steps to produce a strong lineup of leadership products. We will continue to invest in our future process technology roadmap, but we will be pragmatic and objective in deploying the process technology that delivers the most predictability and performance for our customers, whether that be in our process, external foundry process, or a combination of both. Our advanced packaging technologies combined with our disaggregated architecture give us tremendous flexibility to use the process technology that best serves our customers.”

Swan gave some examples of changes in the Intel roadmap with regard to 7 nanometer production. Now, the Xe datacenter GPU code-named “Ponte Vecchio” will be released in late 2021 or early 2022. Ponte Vecchio GPUs were originally slated for early enough in 2021 for the “Aurora A21” supercomputer at Argonne National Laboratory to be on the November 2021 Top 500 supercomputer rankings, paired with 10 nanometer “Sapphire Rapids” Xeon SP CPUs. (You can bet that Argonne is none too happy about this.) The revised Ponte Vecchio GPU will, as Swan put it, use external and internal process technologies combined with Intel’s own chip packaging techniques, which presents some interesting possibilities. The “Granite Rapids” Xeon SP processors will slip to the first half of 2023 compared to the expected launch in early to middle 2022. Blazing the 7 nanometer trail for Intel will be a Core chip aimed at PC clients, now coming in late 2022 or early 2023 and again about a year later than expected to market.

You would think that this slippage would be a great boon for AMD and the Arm collective, and maybe even help IBM’s Power CPUs. Recent history would suggest that Intel’s slip is not as much of a gain for its rivals as you might expect.

Making Hay While The Sky Is Partly Cloudy

It is hard to imagine doing better than Intel is already doing, all things considered. Including increasing competition with AMD, Nvidia, the Arm collective, and Xilinx for compute and in the case of Nvidia (thanks to Mellanox) networking.

In the quarter ended in June, Intel had $19.73 billion in sales, up 19.5 percent, with gross margins up 6.4 percent to $10.51 billion, operating income up 23.4 percent to $5.7 billion, and net income up 22.2 percent to $5.11 billion. Intel is bringing slightly more than a quarter of its revenues to the bottom line, and that is about as good as it gets for most high tech manufacturers. (Apple, by comparison, brought only 19.3 percent of revenues to the bottom line in its most recent quarter, which is one reason Apple is switching to its own Arm chips and away from Intel Core processors for PCs, and we would not be surprised if Apple switched to OCP server running Arm chips for its datacenters at some point for the same reason. Why put all of that cash inside Intel?) These are scratches, not dents, in Intel’s armor. At least for now. Apple is not one of the Super 8: Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Facebook in the United States and Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent, and JD.com or China Mobile in China. As long as Intel can preserve the bulk of its business with these hyperscalers and cloud builders and for the next couple of hundred smaller players, and still hold its ground among risk-averse enterprises, then it can keep raking in the dough.

Data Center Group had a great quarter in terms of revenues and profits, but those profits are under pressure and no doubt because of increasing competition from AMD and the Arm collective. Intel is having to give more compute for the dollar at list price and we suspect cut deeper deals with the bigger players to keep AMD and now increasingly aggressive Ampere Computing and Marvell out of the datacenter with their Arm server chips.

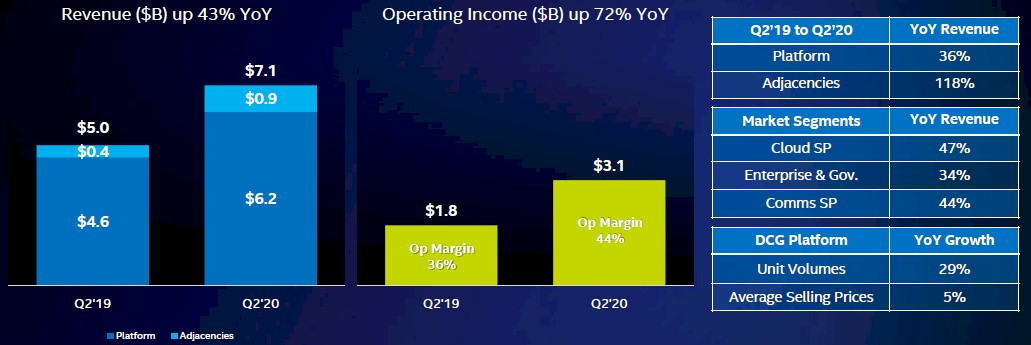

In the quarter, sales of platforms at Data Center Group – server chips, chipsets, motherboards, and sometimes whole systems – rose by 35.8 percent to $6.18 billion. Adjacency sales in Data Center Group – network interface cards, switches, and other stuff – grew by 117.7 percent to $936 billion, we think in large part due to the addition of Barefoot Networks and its programmable switches and a new wave of Ethernet adapter cards. (Intel doesn’t ever give any details within these categories, so it is hard to say.)

In a way, the coronavirus pandemic is helping Intel much more among the hyperscalers and cloud builders than it is hurting it with enterprise customers, and in fact, spending on chippery by enterprise and governments was boisterous – albeit against a very easy compare:

The cloud service provider segment – what we here at The Next Platform call hyperscalers and cloud builders – saw 47 percent growth, and communication service providers (telcos and others) drove 44 percent growth. Intel is able to drive higher average selling prices, and has been bragging about that for many quarters now, but we strongly suspect that Intel is discounting deeply and giving a lot more compute and other features to drive that ASP, and the pressure on its operating margins in the Data Center Group strongly suggests this is indeed happening. A comparison between Q4 2019 and Q2 2020 is illustrative. Two quarters ago, Intel had $7.21 billion in sales at Data Center Group, with an operating profit of $3.47 billion. In this quarter, Intel had $7.12 billion in sales, but only drove $3.1 billion in operating profit. In the prior three quarters from Q3 2019 through Q1 2020, operating profits averaged 49 percent flat, but dropped to 43.5 percent of revenues in Q2 2020. Operating profits were a relatively meager 36.1 percent of revenues in Q2 2019, and that is why the year-on-year compares look so rosy. The first half of 2019 was a relatively slow time in server buying, with the hyperscalers and cloud builders taking a breather. And Intel expects for them to take another breather starting in the third quarter of this year and into the final one.

We wonder how much Intel is eating into its future “Ice Lake” Xeon SP chip sales with the deals it is cutting today. With unit volumes up 29 percent against ASPs being up only 5 percent, we think Intel might be selling a bit of its future to cover its revenue stream needs right now. (That’s the smart thing to do, particularly with the roadmap being a bit smudged.)

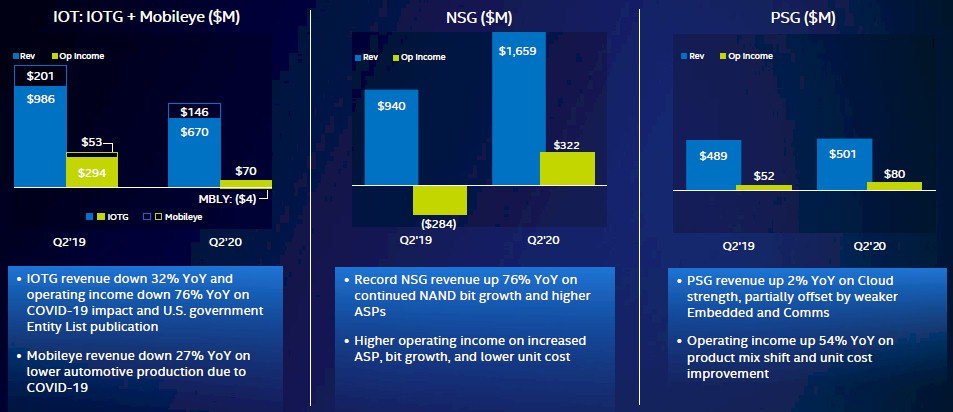

Intel talks about data-centric businesses as a kind of proxy for non-client products, and here is how they stacked up in Q2:

Intel’s IoT business was hit particularly hard by the pandemic due to reduced spending by car makers and governments, and by export controls put in place by the US government. The Programmable Solutions Group unit, which sells FPGAs formerly under the Altera brand, had 2.5 percent revenue growth to $501 million in Q2 2020, with operating profits up 53.8 percent to $80 million. And lo and behold, Intel’s flash and Optane memory group not only had 76.5 percent growth to $1.66 billion, but it turned $322 million in operating profits after many, many quarters of losses on the same scale each quarter.

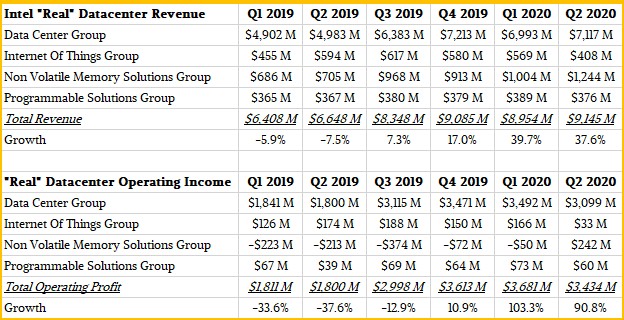

The way Intel talks about itself does not really perfectly reflect its true datacenter business, and we take a stab at trying to reckon how much “real” datacenter business Intel does each quarter by peeling apart parts of all of its businesses and separating them into datacenter and client – as Intel itself should do. Here is what the table for recent quarters looks like for this “real” datacenter business at Intel:

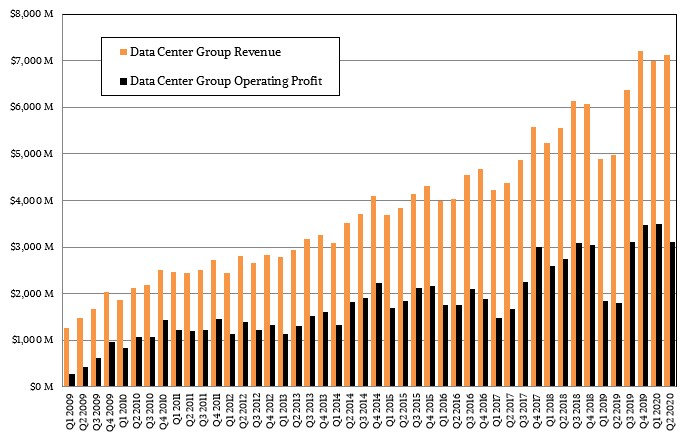

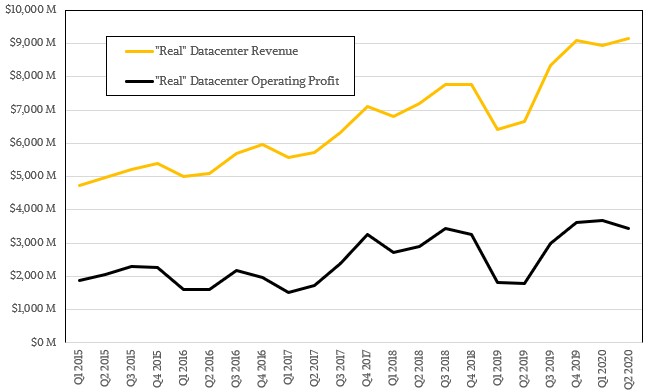

And here is the trend line for a longer term view of the revenues and operating profits for the “real” datacenter business over the past several years:

It is hard to say what the new normal really is looking at this data, but what is perfectly clear from the trend is that the ups and downs of the revenue line are getting more dramatic but the overall trend line is up and to the right at a reasonable slope. The operating profits are not trending up in quiet the same way across all of these datacenter lines, and we think the profit swings are also quite large. The operating profits are a bit lower than the reported Data Center Group figures, but the revenues are considerably larger and have averaged just north of $9 billion in the past three quarters.

A lot depends on how hard Intel can squeeze the 10 nanometer fruit while it waits for 7 nanometer to ripen quite a bit later than it expected.

What has happened to INTC’s manufacturing performance over the last 4 years is SHOCKING! Are management incentives and controls part of the problem?

The DOD had better start thinking about how to invest in an independent chip-maker on US shores. If there’s anything that warrants government investment, it’s this.

Intel is sandbagging 10 / 7nm, cost optimizing as a 10 nm follower letting process leaders take the 7 / 5 nm factor cost increase why Intel studies their moves.

Wasn’t Intel’s 10 nm supposed to be comparable with TSMC 7 nm?

Moving in at TSMC enables Intel to learn even more from their TSMC process leading competitor which places a drag effect on AMD, ARM World, Nvidia wafer starts at TSMC.

Nvidia is the first casualty.

For Nvidia I have high hopes at Samsung foundry if 8 nm can produce frequency. We know Samsung produces for low power.

Intel reverses the obvious and knows how to put on an act. Mother bird dragging what appears to be her broken wing on the ground, too lure the fox away from her nest.

At inflection point between process saturation and advanced packaging Intel plans to leap frog the question is when? Every move is coordinated and there is no transparency unless one strategically thinks like Intel, in reverse.

Intel stock price dip, BFD, stock dip conceals sandbagging a small cost to observe and study on Intel’s terms; misrepresented.

It’s all part of the Intel plan.

Monolithic dice remain cost : price competitive when you own your mask shop producing area optimized multi core dice; Core or Xeon. We’ll see more of this from Intel where AMD is limited financially, limited on wafer starts, and restrained in product volume.

At Intel cost : price and margin, process trailing one node is margin advantageous for profit. Intel 14 nm plug & play kibble continues to rule commerce running the business of compute. The ultimate consequence of monopoly choice from a supply side producer in excess of real time demand, albeit, conscious of the necessity for change to reserving for demand.

Two nodes behind, however does raise a question. So Intel cozies up to TSMC for a closer look inside.

Intel and associate network the ultimate insiders.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing