There is an equally virtuous and vicious cycle that propels all computing: Innovation requires competition to propel it, and competition requires innovation to meet it; repeat or fade.

Nothing illustrates this better than the rise of Intel in the datacenter against proprietary and RISC/Unix server makers over the past three decades, and the rise and fall and resurrection of archrival AMD in those same datacenters. But resurrection is not enough for AMD. The company wants an even bigger slice of the datacenter pie than it was getting back in the roaring days of the Opteron processors – and the top brass at AMD laid out a plan to do just that at its Financial Analysts Day meeting in San Francisco.

Rather than get into all the nitty gritty details of what AMD said about its technology, we are going to start by counting the money AMD expects to be counting from its datacenter business between now and 2023. And then we will talk about what the company’s techies said about its CPU and GPU roadmaps – and the competitive positioning they will have – that make chief executive officer Lisa Su and her team believe they can get there. And with enough confidence to lay it all out to Wall Street in AMD black (well, a sort of dark gray) and white.

People First, Products And Profits Will Follow

It goes without saying, although we have said it before, that Lisa Su is the best thing that has happened to AMD since Jerry Sanders, its chief executive officer from 1969 through 2002, founded the chip maker with a bunch of engineers from Fairchild Semiconductor, which also spawned Intel among many other of the so-called Fairchildern of Silicon Valley. Su, who took the helm of AMD in 2014 at perhaps its lowest point after it had all but abandoned the datacenter, has put together a very good team of people who have turned the company around.

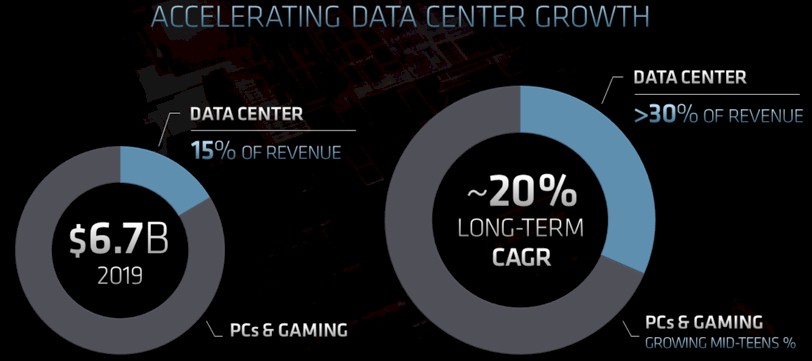

Of all of the charts that AMD presented during its presentations to Wall Street, this was the most important one, which was presented by Devinder Kumar, the company’s chief financial officer. Take a look:

This chart is the important one because it shows the effect of all that engineering and sales effort that has happened since 2015, when AMD had $3.99 billion in sales, mostly from low-end PC chips, up through 2019, after a three year surge into the desktops, laptops, and datacenters of the world as well as into game consoles with both its CPUs and GPUs. AMD exited 2019 with $6.73 billion in sales, and just a little over $1 billion of that was for CPUs and GPUs sold into the datacenter. The rest of the company’s sales came from CPUs and GPUs sold to PC and game console manufacturers. But the second reason this chart is important is because it not only shows the long-term growth for the overall company out to 2023, but it also shows that AMD expects to more than double the share of its revenue pie from the datacenter against that rapidly growing overall sales.

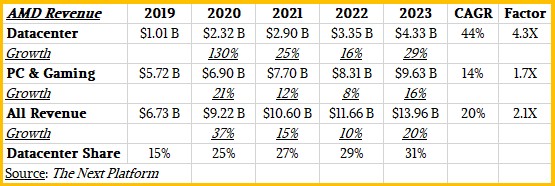

There are a lot of ways to get from the actual 2019 sales to the anticipated 2023 sales for AMD, and neither Devinder nor Su were about to be very precise about how they intend to work with the team to get AMD to that end state. But we have some ideas about what might happen.

When we analyzed AMD’s fourth quarter and full year 2019 revenues back in January, we figured that based on momentum and Intel’s difficulty in getting beyond its 14 nanometer Xeon SP processors and its lack of discrete GPUs for the datacenter that AMD should be able to more than double its datacenter revenues in 2020. The game consoles from Microsoft and Sony are going to push up PC and gaming sales at AMD, and so it eating into market share, as the company has done for eight quarters. If you add our 2020 model to what happened in 2019 and then pay around with the numbers to end up with around a 20 percent compound annual growth rate for the whole business and more than a 30 percent market share in 2023 for the datacenter CPU and GPU business. Here is what our model looks like, then:

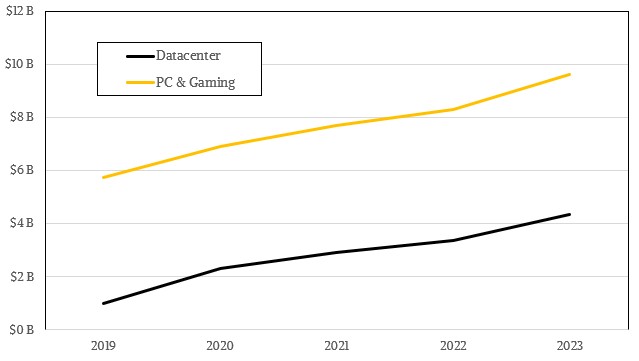

And for those of you who think visually, like we do, here is the same data in a chart:

When AMD says greater than 30 percent share for the datacenter CPU and GPU sales, we went pessimistic and said it would be 31 percent. But it could be a higher percentage of overall sales, of course. But based on what AMD knows, its overall revenues as it exits 2023 are going to be pretty close to $14 billion, based on the overall “around 20 percent” CAGR that was given for company revenues between 2019 and 2023, inclusive. As we have said, we expect growth rates to be higher than this for 2020 and then to taper off as the years go by, which is natural enough given an eventually revitalized Intel.

Now, let’s consider Intel and Nvidia, who are not standing still here but who have dominant share of datacenter CPU and datacenter GPU sales, respectively, here at the beginning of 2020 and clearly for the past decade. We have said this before, and it bears repeating. Intel accounts for something on the order of 99 percent of server chip shipments and probably on the order of 90 percent of server revenue share; its share of server CPU revenue share is lower because there are more expensive processors out there (for how long, we shall see) but this high price that IBM can command for its z and Power motors is actually offset in the CPU revenue pie somewhat by the rise of less expensive AMD X86 server chips and the relative handful of Arm server chips sold by Marvell, Ampere Computing, Huawei Technology, and a few others.

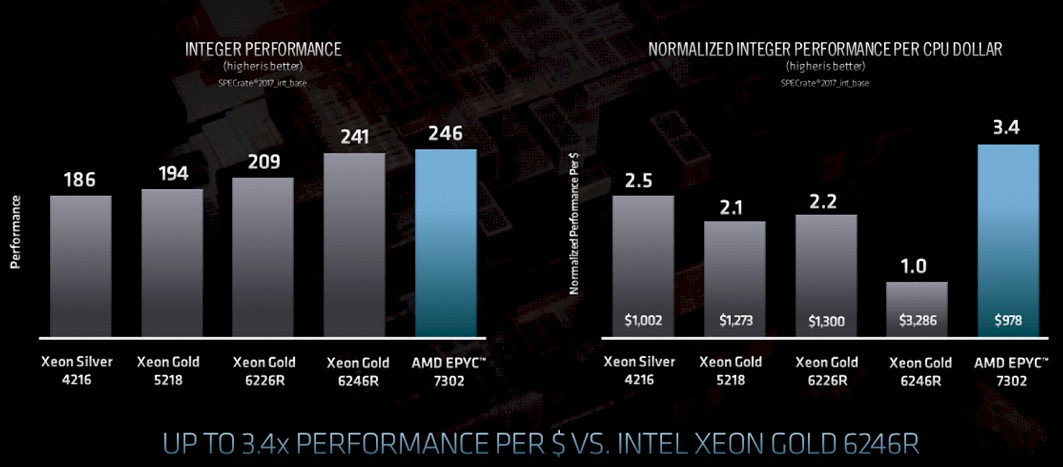

In a flat market, based on the current TCO difference that AMD is showing with its “Rome” Epyc 7002 series compared to even the just-updated “Cascade Lake R” Xeon SPs from Intel, every $1.00 in Rome chip sales removes somewhere between $1.40 to $3.40 in Intel Xeon SP sales, based on the price/performance advantages that Forrest Norrod, general manager of the Datacenter and Embedded Systems Group at AMD, cited in his presentation below:

This chart above compares the 16-core chips that Norrod characterized as being “in the heart of the market,” and if you average it, call it something around $2.25 lost for Intel for every $1.00 that AMD gains.

In many cases, that savings will be redeployed as additional capacity, which would further depress Intel’s revenues and in other cases – particularly if the economy cools thanks to the coronavirus outbreak – it will just simply not be spent at all. Either way, Intel takes the revenue hit. What has saved Intel thus far is that the market for servers has been expanding, with some blips here and there, but as we pointed out a few weeks ago, for the full 2019 year, Intel’s revenues in the Data Center Group revenues were only up 2.1 percent to $23.48 billion, but its operating profits actually fell by 10.9 percent to $10.23 billion. There is more than server CPU sales in those figures, which include motherboards, systems, switching, and other products. AMD is most definitely having an impact on Intel’s bottom line and if server spending is curtailed, it will start hurting its top line, too, which will amplify through its increased costs for bringing its 10 nanometer and 7 nanometer CPUs and GPUs to market. As long as the market is expanding, everybody can do some business. But it will get very ugly if the market tightens and Intel can only lose both revenues and profits in a price war. There is no way to maintain at all. Period.

To a certain extent, the same holds true for Nvidia’s position in GPU compute, where both AMD and Intel are going to be trying to take away business and Nvidia can only cut price and lose revenues and profits or keep prices high and lose revenues and profits. The only thing that has saved Nvidia from this impact is the vast software ecosystem it has built over a dozen years. Hundreds of applications and untold numbers of homegrown code has been ported to Nvidia Tesla GPU accelerators and it is the easy, safe platform choice for GPU acceleration. But you notice how those who can control their own software stack — the Oak Ridge and Lawrence Livermore labs of the US Department of Energy come to mind — don’t care about that as much because they have their own agnostic programming stacks and their own applications. And if they work together to make the Radeon Compute Environment, or ROCm, good enough, and the hyperscalers and cloud builders that want GPU acceleration help out, AMD can build an ecosystem in a much less shorter time than it has taken Nvidia. Intel and AMD can, with Nvidia’s help as it makes accelerated computing more prevalent for its own enlightened self interest, turn Nvidia’s goat path that turned into a dirt road and then turned into a two-lane highway going through the mountains into a four lane that has bridges and tunnels that is a wider and smoother ride for everyone.

AMD expects for its Radeon Instinct GPU compute business to obviously grow a lot faster than its Epyc CPU business, and that is just because it is so much smaller. Right now, we reckon that AMD is getting two thirds of its datacenter revenues from Epycs and one third from Radeon Instincts. But in the fullness of time, the revenues should reflect the ratio of CPU to GPU compute normalized to prices, and that should mean a lot more revenue coming from GPUs than CPUs. So by the time we get to 2023, the revenues from GPUs could be a lot larger portion of the AMD datacenter pie. Given the 1:4 ratio of the exascale-class supercomputers, “Frontier” and “El Capitan,” being built by Cray for the DOE using AMD Epyc and Radeon Instinct motors, and assuming that GPUs will cost more than CPUs in these machines, the fact that AMD is winning the GPU portions of these hybrid machines is truly significant for its top and bottom line in its datacenter business. If AMD can offer a TCO advantage on its GPUs versus Nvidia GPUs – and the performance and price of the Frontier and El Capitan systems suggests it will be able to at least for these big deals because AMD did, after all, win the GPU parts of these contracts – then Nvidia will be feeling a similar kind of pressure.

A lot depends on the prevalence of GPU acceleration. Right now, we estimate that only somewhere around 1 percent to maybe 2 percent of servers worldwide have GPU acceleration. While many have eight or even sixteen GPUs for every two processors – ratios of 1:4 or 1:8 – it takes a lot of big hybrid machines to try to push GPU sales up to anything even close to that of CPU sales inside of servers. Based on some guesses with some very wide error bars, GPU sales for servers in 2023 could be equal to CPU sales for servers if accelerated computing takes off for HPC and AI workloads and both are more widely deployed in the cloud and in enterprises. That’s optimistic, obviously. But CPUs are a lot less expensive than GPUs, and are worth it given the massive amount of compute they pack.

What we are saying – and what AMD certainly did not say – is that the chip maker could have a $2 billion or so Radeon Instinct business by 2023, somewhere around 6X bigger than it is currently and probably driving pretty decent margins. For this to happen, AMD has to be very aggressive on Radeon Instinct prices and it has to make it up in volume.

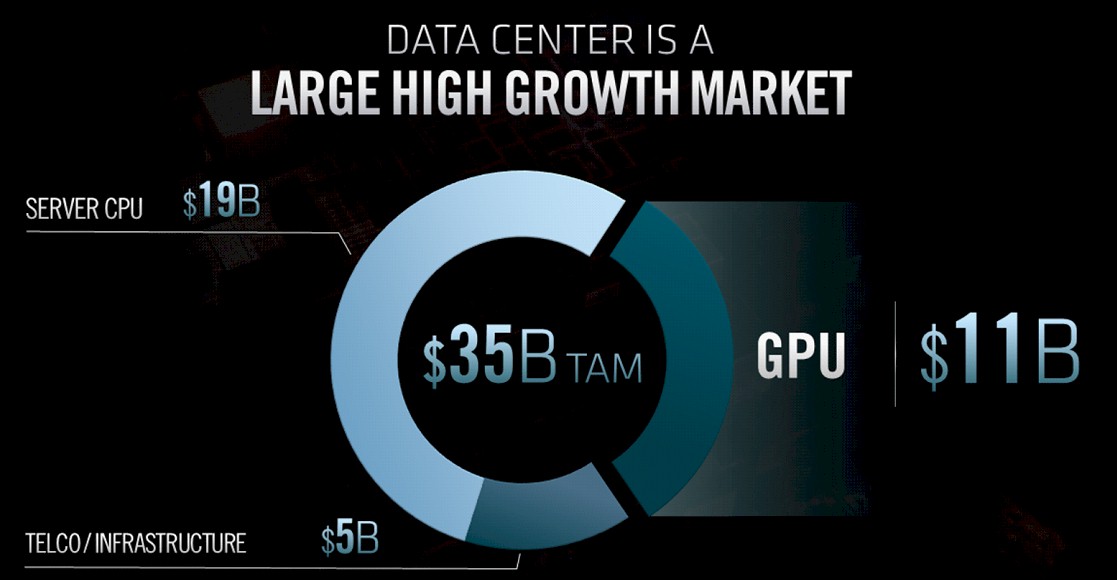

This is not crazy, given the total addressable market that AMD sees in front of it out there in 2023:

Getting to somewhere around $2 billion in Radeon Instinct sales does not sound like an overreach in a market that AMD pegs at $11 billion in 2023, which would be an 18 percent revenue share. The server CPU addressable market will weigh in at $19 billion, and the telco/infrastructure space will be another $5 billion and having both CPU and GPU components. Ignore that last bit for the moment. AMD’s revenue share of server CPUs, in this scenario with only $2.3 billion in sales leftover after subtracting out $2 billion for the GPU accelerators, would be only 2.3 percent. That sounds absolutely attainable – particularly if AMD keeps the prices low and the performance high. (By the way, we think that server CPU TAM will shrink, or at least be smaller than it would otherwise be, because AMD has entered the market and is aggressive and its revenue share will be proportionally higher than this math shows.)

It’s Money That Matters

One last piece of money math. If you look ahead to 2023, and you think the datacenter TAM is exactly as AMD expresses it, then AMD’s share of that TAM, with at least $4.33 billion in expected sales based on the math in the table above, that is 12.4 percent. We all know that when the Opteron was humming along, AMD was able to get 20 percent share of server CPU shipments and in some cases peaked at 25 percent share. If the datacenter compute TAM grows at a meager 5 percent per year and if AMD can average 25 percent growth in its datacenter business, which is much less than the 44 percent average it expects between 2019 and 2023, then by 2026 or so AMD will have around 20 percent of a $40 billion market and by 2027 it will have around 25 percent of a $42.5 billion market. So basically, the company is a tenth of the way there, but Lisa Su & Company see a path to being a real, sustainable, and impactful high performance compute — in the broad, not narrow, sense of the term — engine supplier.

2019 was a hell of a good start. And if there is a recession right now, as there was in late 2007 but really hitting really hard in 2009 just as Intel got its Xeon act together with a 64-bit “Nehalem” redesign, we suspect that AMD might be the beneficiary and not Intel this time around. AMD will have a bigger share of a somewhat diminished server CPU and GPU market.

Now that we have counted the money that isn’t here yet, stay tuned for our analysis of the AMD Epyc CPU and Radeon Instinct GPU accelerator roadmaps that will try to make that cash materialize from whiteboards and chip fabs.

Conspicuously absent from AMD’s presentation was talk of its “WX”(Formally FirePro branded) line of GPU offerings for the Professional Graphics Workstation market where Nvidia gets loads of business. And one should go over to Techgage and look at those RTX Quadro benchmarks and those SKUs come with Tensor Cores and Ray Tracing cores and AI image effects has been big with Adobe/Others for a few years now. So Pro Graphics Workstation GPUs need tensor cores in addition to ray tracing cores as that Pro Graphics Workstation market has wholeheartedly embraced Ray Tracing and AI based image/animation effects.

Adobe has a feature for using an AI(Tensor Cores) based trained algorithm to pull out a part of an Image from its background and doing that on a image/video and no need for any chroma screen setup to key over parts of an image/images over another background and having to use a complicated compositor setup. So greatly improved workflows in some video and single image tasks that make use of AI trained algorithms to get the work done.

So AMD’s WX branded Professional Graphics Workstation cards better be CDNA based with more of the RDNA graphics capability included for the WX branded Pro Graphics Workstation branded GPU parts. Nvidia’s RTX Quadros doing 2D and 3D Animation rendering workloads and making use of Tensor Cores and Ray Tracing cores to speed up the rendering process via dedicated GPU hardware blocks will have AMD fruther behind unless AMD starts to focus more on Professional Graphics oriented GPU hardware features that require RDNA and CDNA branded GPU feature sets.

But I’d imagine that even CRNA based GPUs will still have those tessellators, TMUs(Texture Minipulation Units), and ROPs(Raster Operation Pipelines) in addition to the compute additions that the Professional Graphics Workstation end user will make use of and AMD can not pass up the better markups in the Professional Graphics Workstation market where currently Nvidia is king, GPU accelerator market as well.

Nvidia has its NVLink interfacing its GPUs with OpenPower Power9/10 CPUs and that level of CPU to GPU coherency and AMD will have that fully implemented by the Time of Epyc/Genoa using that full Infinity Architecture(Rebranding/Suprabranding of the Infinity Fabric branding) to include both Epyc CPUs and Radeon Instinct/Other GPUs interfaced more coherently via the infinity Fabric that will be AMD’s fully in-house answer to Nvidia’s/OpenPower’s CPU to GPU NVLink interfacing.

AMD’s CEO and CFO where big on stressing gross margins and gross margin growth so AMD needs to give more deference to the Professional Graphics Workstation market segment where like the HPC/AI market the GPU markups are well above any consumer gaming GPU margins/markups. So AMD’s still not fully focused across all the potential TAM without mentioning that Professional Graphics Workstation part that’s the Pro Graphics Workstation GPU market segment.

There also needs to be Some Epyc Branded CPU workstation capable parts that are above an beyond Threadripper’s limited ECC memory support(Does Not support RDIMMs) and limited to 256GB max memory size. And animation rendering needs can vastly outstrip 256GB and need 1TB larger memory sizes. So that’s requiring Epyc and 8 full memory channels instead of only 4 for any Threadripper branded parts. AMD really needs to brig that Infinity Architecture to the Professional Graphics Workstation market with Epyc/Genoa and some Workstation Genoa parts that’s directly interfaced via the Infinity Fabric/Infinity Architecture and bring a more coherent HSA to fruition where Nvidia will have no ability to directly compete unless Nvidia take up an OpenPower license of its own and brings up some CPU competition as well as GPU.

Excellent take thank you Count_de_Money,

I am especially afraid that AMD is going to drop the ball and fluff workstations: but I would rather have better support for Epyc than plump up Threadripper, because the unmet demand that’s for grabs in graphics has been satisfied most unsatisfactorily so far by adapting 4C platforms and as you say, RAM appetite is unlimited for moving picture graphics and professional users are already juggling multiple maxed out Xeon workstations. This market wants v4 lanes and single root topology and maximum L3 and SP Epyc is a bargain and we simply need a push for memory compatibility and ISV certification to be the dominant part in 2021.

“much less shorter” So, longer then?

Intel roadmap shows 7nm Ponte Vecchio GPUs with PCIE5 and CXL and HBM2E in 2021. They are also already releasing beta versions of their oneAPI processing libraries for HPC. Looks to me like AMD HPC GPUs will have another significant competitor exiting 2021.

Yup. I was being a little too quick with my mouth, and obviously I have written about these very things.

We expect that strong demand for data center space, combined with limitations on supply capacity and pre-existing skills shortages in the sector, will result in upward price pressures

AMD processors was good for gaming with good GPU speed