All of the commercial platform creators in the world, since the dawn of time, which arguably started in the enterprise in April 1964 with the advent of the System/360 mainframe, wants the same things. They want to create a flexible, integrated, and useful system where data can be stored and applications run against it or create the starting data, and one that provides the maximum value to customers while at the same time allowing them to extract the maximum value out of customers.

In its long history, IBM has been among the best at creating complete systems and while also being a company that enterprises around the world could depend upon. Not that Big Blue always created the best platforms, mind you, or was always first with innovations. But IBM has been first enough times and running with the pack enough times and only a true laggard a few times that it still has a $60 billion systems business, based on System z mainframes running legendary and legacy operating systems as well as Linux and based on Power Systems running the legendary, legacy, and truly innovative IBM i operating system as well as the AIX variant of Unix and Linux.

We reviewed these IBM platform businesses as part of our coverage of Big Blue’s fourth quarter financial results, which were unveiled two months after IBM had spun out its $30 billion Kyndryl managed services business, representing more than half of the Global Services behemoth that had defined the company since the early 1990s. IBM kept the juicy bits of Global Services – consulting, tech support, application operation, and financing – but only the parts that are relevant to and supportive of those System z and Power Systems platforms. The Red Hat acquisition is one way to make those platforms – as well as the X86 hardware commonly deployed in enterprise datacenters – more relevant. We think IBM would gladly focus on selling its existing customers the OpenShift container platform and not worry so much about deploying Red Hat Enterprise Linux on competitive hardware, but it needs to keep supporting Linux on OPP – Other People’s Processors – if it doesn’t want to starve the goose with the red eggs that turn into black ink when they fall to the bottom line.

We did a little more analysis in the wake of that story last week, and here is the annualized model we now have for IBM’s revenues by product divisions:

Items in red bold italics are estimates made by The Next Platform based on pie charts IBM supplied in December to Wall Street for its 2020 results absent Kyndryl to help analysts start thinking about the new Big Blue and on a similar set of pie charts IBM supplied for all of 2021 as part of its Q4 2021 financial report. We had to do some guesstimating based on old financial presentations and hunches to fill in the gaps for 2019. All we have to say about this is that IBM could stop screwing around and just publish this table each quarter and actually tell Wall Street what its groups and divisions are doing. But, this makes us feel useful, so we do what we can to understand.

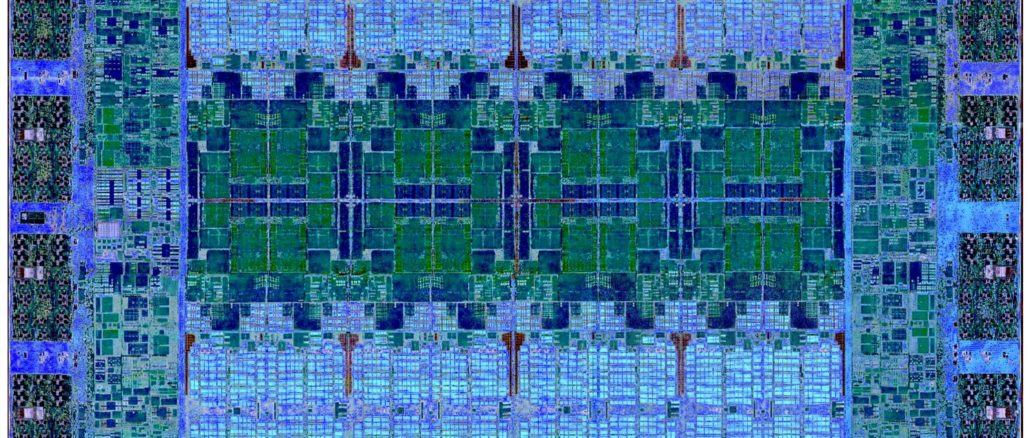

Both the Power Systems and the System z lines are getting ready for new processors this year, and are thus IBM is looking ahead to a pretty good 2022 on both fronts. The Power entry and midrange machines will be upgraded with the 16-core “Cirrus” Power10 processor, which has already made its way into the high-end, 256-core “Denali” Power E1080 machine that launched last September and that ramped up to its full 16-socket NUMA configurations as 2021 came to an end. (Only 240 of those cores on the Cirrus chip are activated at the moment for the purposes of boosting the yields out of Samsung’s foundry with its 7 nanometer process.) The System z mainframes will be getting the eight-core “Telum” z16 processor to create the 32-socket, 256 core System z16 machine. The Telum chip is also implemented in 7 nanometers at Samsung, and there is a good chance some of the cores will be dudded to improve yields as happened with the Power10. Importantly, both have on chip AI accelerators tuned for inference.

We point these product transitions out because they explain why IBM’s systems sales shown in the table above, which includes the hardware and operating systems together, were not back to their 2019 levels. The System z line actually did pretty good for all of 2021, up 8.2 percent to $3.05 billion. Distributed infrastructure, which is IBM’s term for the combination of Power Systems and storage revenues across disk, flash, and tape arrays, was down 7.9 percent in 2021, but held more or less steady from 2019’s levels despite the pandemic. If you put a gun to our head, we would say Power Systems alone represented $2.34 billion in sales in 2019, $2 billion flat in 2020, and $2.01 billion in 2021. IBM probably has 5,000 to 6,000 System z customers in the world, but it has 140,000 or so Power Systems customers – most of them running IBM i on small machines but a lot of them running AIX (and sometimes IBM i and Linux) on very big machines.

What we do know for sure is that IBM will not be getting a big supercomputing bump for Power Systems this year and next, as it did in 2018 with the 200 petaflops “Summit” supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the 125 petaflops “Sierra” supercomputer at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory because HPE/Cray has won the follow-on 1.5 exaflops “Frontier” supercomputer deal at Oak Ridge and 2.3 exaflops “El Capitan” supercomputer deal at Lawrence Livermore – both of which use AMD CPUs and GPUs. Still, we think IBM will have a better 2022 in systems than it had in 2021 – and very likely a more profitable one because it won’t be spending most of its effort on those exascale systems, which bring juicy revenues but little profit.

To get a handle on what IBM is thinking about the future of the Power Systems business, we had a chat with Ken King, who was named general manager of Power Systems last July as the prior general manager, Stephen Leonard, moved over to Kyndryl to be head of its global alliances and partnerships. Leonard told us last May that technical computing – HPC simulation and modeling – represented something on the order of 10 percent, maybe 15 percent at times, of Power Systems revenues, and that AI had been folded into enterprise computing. While IBM has had some big wins in 2017 and 2018 with AI/HPC hybrid supercomputers, most of its HPC business was on X86 iron in the past, and that HPC business has been part of Lenovo for eight years now. (Hard to believe, isn’t it?)

King joined IBM after graduating with a bachelor’s in computer science from Rutgers University in 1984 and went on to get a master’s in business administration at the University of Denver. King has had many roles in his long career at Big Blue, including being in charge of technical strategy for its Software Group and getting the techies at IBM Research to actually work on commercial issues with customers. King has managed acquisitions and integration (for the Rational and Telelogic deals IBM did) and was the business line manager for IBM’s grid computing efforts in the early 2000s. In 2009, King was put in charge of IBM’s patents and IP licensing and eventually became general manager of all of its intellectual property. In 2014, in the wake of the partnership with Google, Mellanox, Nvidia, and Tyan to create the OpenPower Foundation, King was put in charge of this effort. (OpenPower is still doing stuff, and last year announced a Power-based, fully open source baseboard management controller for servers, called LibreBMC, which is backed by Google.

It is unclear just how many Power-based servers Google has in production these days, but it is safe to say that OpenPower did not get the momentum it needed to create a volume alternative to X86 and Arm in the datacenter, even with the opening of the Power instruction set back in August 2019. That said, IBM’s commitment to Power is unwavering, and it is working on Power11 and thinking about Power12 even as Power10 is not yet fully delivered to the market. And now, we want to know what IBM plans to do to boost sales of the Power line.

Timothy Prickett Morgan: Let’s start with the obvious. I’m expecting the other Power10 machines in May or June, and I know you can’t talk about that, so how it is the Power E1080 doing?

Ken King: We just we just put the high end out and the low end is coming out in 2022. I can’t go into specifics and details, but you have a reasonable guess. The high end is starting out very strong.

You know, it’s sort of a tale of two cities. We’re at the front end of our Power10 high end and we’re at the very back end of the Power9 scale out. We did the launches in reverse with Power9, first with scale out and specifically in the CORAL supercomputers at the Department of Energy, which was the key element driving that the CORAL schedule, and then we did more scale out machines, and then the high end. So the scale out cycle is much longer than normal.

All I can say at this point is that we are driving a lot of good return on Power10, and we are seeing growth in the first phase of it. We are doing well with SAP HANA workloads, and have had a number of big wins with SAP HANA, as you can imagine, because we had record-breaking benchmarks with SAP. Our eight-socket server was better than anybody else’s 16-socket X86 server, and when we delivered our three and four node machines at the end of 2021, we had even more compelling benchmark results that drove more client wins.

We’re still cranking away on the Power10 scale out systems and the plans for those remain on schedule.

Moreover, we are going to continue to drive more capability to enable clients to buy with different types of consumption models. And I think that will help in getting many Power Systems customers to see value in upgrading. You talked to Stephen about this last year, we’re also continuing to build out more capabilities and what we call our frictionless hybrid cloud. And that’s for AIX and IBM i and Linux, and it is to have architectural consistency between our on premises and public cloud capabilities, allowing customers to move the capacity they buy back and forth between their public and private cloud setups. We’ve done it in a way where on the IBM Cloud as well as with hyperscalers such as Google and Microsoft there’s no refactoring of applications required.

TPM: And can you make the pricing absolutely consistent as well, between the IBM Cloud and on premises gear? I know they’re getting closer and closer, but can you get to the point where you just say it is X dollars per hour for a certain amount of compute and Y dollars per hour for memory, and it doesn’t matter where the machine is physically located? I realize that the IBM Cloud has to pay for power, cooling, and space so that has to be reckoned with in some way. . . .

Ken King: There are different cost elements that may create some challenges. But generally, that’s the goal, so it is easier for clients run their applications on a Power-based private cloud on premises and then decide to take some of that capacity and burst it to the IBM, Microsoft, or Google public cloud and be able to pay the same amount for that. That frictionless model is what we’re moving towards, and it means you don’t have to refactor the applications, but also that all elements of how you your user experience with the platform are consistent in the hybrid cloud environment.

We’re also looking to extend that by partnering with more managed services providers and with other major cloud providers, the objective over time is not just to have a consistent hybrid cloud, but a consistent multi-hybrid cloud strategy for the Power platform. And I think the more we’re able to do that, as we go through time, the more the clients who are sitting on Power6, Power7, and Power8 will see different upgrade paths and value props associated with them.

The other thing we’re doing is we’re creating a low latency environment between AIX on premises and AIX in the IBM Cloud and Linux. We have Linux with OpenShift, with Ansible, on Power. So that it’s easy for clients that are running on premises and in the public cloud to be able to use Ansible, to have the same user experience of administering AIX like they are administering Linux, no matter where it is.

Now, if you want to take those systems of record on IBM i or AIX and do some modernization and extension work, or add some new user experience on top of it, I can do that very easily in a low latency environment linking AIX and IBM i partitions to Linux partitions.

TPM: What we really want to know is what is IBM’s aspiration for Power among traditional HPC simulation and modeling customers. What’s the opportunity? My take on IBM in HPC is that together with Nvidia and Mellanox, you built some good pre-exascale supercomputers, and for whatever reason, you didn’t get the second dip with the exascale machines. But maybe that is a blessing in disguise because we strongly suspect that IBM did make any money – meaning profit – from those big deals. You get public relations and revenue to pay for research and development out of those CORAL deals, but it might be far more grief than it is worth.

I understand that Power10 has excellent vector and matrix math capabilities, which will make it a good platform for AI inference workloads that are embedded in enterprise applications.

Ken King: We do separate our enterprise AI from technical computing. And as you say, we didn’t do CORAL2, and without getting into specifics, the HPC segment is a challenging space from a gross profit and profitability perspective. HPC drives a lot of volume drives, and a lot of revenue. But it is it is a very challenging value proposition when you want to get profit and use that profit to drive investment in the platform.

But that said, when we see HPC opportunities that make sense, from a profitability perspective, we aggressively going after them.

For Power10, we don’t have HPC as one of our top targeted segments. We engage here, and will continue to engage when see the merging of traditional HPC and AI. But we are enabling clients to be able to do their AI inferencing where the data is versus having to move the data to the compute on an accelerator. I think that can play very well in HPC, and it plays really well in the enterprise.

But our real focus with our AI strategy is in the enterprise, where we see a significant amount of opportunity as our clients are looking for ways to gain better insights in their data. And they want to be able to use inferencing not just at the edge, but in the datacenter to drive more return. We feel strongly that is where our sweet spot is.

My view is that you can train AI models anywhere, but it’s about where you deploy them, where you do the inferencing and where you are actually processing that data. So our strategy is to work aggressively to get the inferencing capabilities built into the ISV and homegrown applications. That’s going to be a significant part of our strategy going forward. There’s much more opportunity for us, with AI inferencing being a bigger market going forward than AI training.

TPM: I don’t know if there is more money in inferencing than in training, but there are going to be more clock cycles once companies embed AI everywhere, and you should sell more Power10 and Power11 because of it. You get to sustain your Power Systems revenue stream and increase it possibly based on that. And Intel’s going to do the same thing with its Xeon SPs and their matrix engines.

The other thing I would observe with HPC, and we see it with Nvidia’s own research, is that the GPUs for HPC simulation and modeling and the GPUs for AI training are starting to fork. So the harmonic convergence between HPC and AI, which IBM certainly benefitted from, might be getting dissonant. And soon, we might be back to buying two different machines, or sets of accelerators, for two different workloads, and that will create a workflow and efficiency problems.

Ken King: And then you are going to have latency issues, too. . . .

TPM: Let me refine the question a little. Just for the core HPC simulation and modeling workloads and Power10 – is there still enough CPU-only compute engine opportunity for Power10 to chase? Or will IBM still peddle GPU accelerated machines for those who want to use Power for AI training or simulation and modeling?

Ken King: We’ve got things in motion that may or may not effectively answer the question. [Laughter] I can’t really answer right now, based on the roadmap and what we haven’t announced yet. But I would just say: Watch this space.

TPM: I just love when people tell me that. And then I do it anyway.

End of paragraph 6: “Importantly, both have” ….. err, what?

At the very least, there’s a full stop missing, but I suspect there’s more text missing also.

All fixed. I dunno.

I think Ken King has it backwards when he says that you can do machine learning on anything but that inferencing really took something special.

Well, it is not so much that it is special, but the models run near the application, and it should be inside the memory footprint and security perimeter of the CPU. This seems like a valid argument for a lot of enterprises. Thus far, the CPU is doing a lot of the inferring. Admittedly, there is not as much inferring outside of the hyperscalers. But it is coming.