In the longest of runs, say within the next five to ten years, in the large datacenters of the world, the server chassis as we know it will no longer exist. We aren’t talking about the bent metal here. We are talking about ending the tyranny of the motherboard, which limits the scale and scope of the unit of compute in the datacenter.

We have been on the disaggregation and composability crusade for over two decades, and have been heartened to see so much progress in recent years. New fabrics have been laid atop various bus and network interconnects to lay the foundational work for creating true disaggregation and composability as we have dreamed of it for so long. We encapsulated our thoughts about why this all matters, and in the current context, back in March in an essay called The Future Of Infrastructure Is Fluid, and we are not going to repeat all of those strategic thoughts now. This is about tactics and getting a report from the field for one of the innovators in disaggregation and composability. Namely, GigaIO.

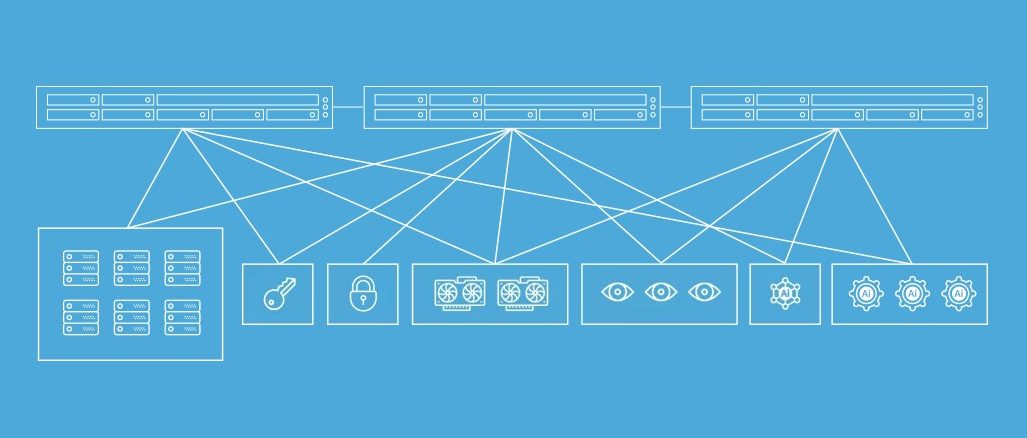

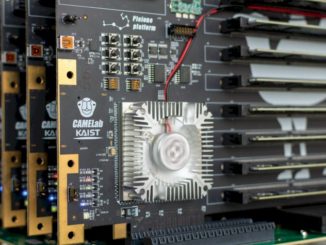

Fundamentally, PCI-Express fabrics take Ethernet and InfiniBand out of the picture, literally chopping the network interface card and all of its protocol and transport out and replacing it with a PCI-Express adapter card to extend the server bus out to any one of a number of PCI-Express switch topologies. To this fabric is added Non-Transparent Bridging (NTB), which allows two devices connected in a point-to-point fashion over PCI-Express to see into each other’s memory and I/O. We discussed this when GigaIO dropped out of stealth in October 2019 and was still working with relatively unimpressive PCI-Express 3.0 switching, which was fairly limited in the aggregate bandwidth of the devices and the port counts possible (what is called radix in the industry). InfiniBand and Ethernet ASICs have much higher bandwidth and much longer links between devices, but they also have much higher latencies.

In early 2020, after the first PCI-Express 4.0 servers were in the field and PCI-Express 4.0 bus adapters were available from Broadcom’s PLX Technologies unit and PCI-Express 4.0 switch ASICs were available from Microchip, GigaIO rolled out a set of PCI-Express 4.0 switches and adapters and updated FabreX disaggregation and composability systems software that doubled up the bandwidth on 24-port PCI-Express switches or allowed for the ports to be split yielding a higher radix of 48 ports. And late last year we went through some total cost of ownership analysis for GPU-accelerated systems with GigaIO to count the cost of underutilizing these very expensive GPU engines. By driving up utilization, you can buy fewer GPUs and get the same work done — and at a much lower cost.

This is one of the key drivers of disaggregation and composability, but so is flexibility in configuration and the desire to have low latency between devices. Memory pooling is also starting to come into play, and will be a big deal when PCI-Express 5.0 is out, doubling up the bandwidth or radix (depending on how you want to cut it) of switches and also supporting the Compute Express Link (CXL) asymmetric coherence protocol developed by Intel and gaining support for just about the entire IT ecosystem at this point. (We talked about Microchip’s future Switchtec PCI-Express 5.0 switch ASIC and retimer chips back in February, and the port counts could be driven as high as 104 at PCI-Express 4.0 speeds or even 208 at PCI-Express 3.0 speeds if people want to stay that low. The top-end future PFX 100xG5 Switchtec ASIC has 100 lanes and an aggregate of 5.8Tbit/sec of bandwidth, which works out to 52 ports running and an aggregate of 725GB/sec of bandwidth.

The coronavirus pandemic dampened the prospects for GigaIO as 2020 was getting started, Alan Benjamin, co-founder and chief executive officer at GigaIO, tells The Next Platform, mostly because people could not get into offices and datacenters to set up new equipment and put it through the proof of concept paces. But as PCI-Express 4.0 servers, adapters, and switches got out there, the disaggregation and composability message started to resonate with customers who were not driving high utilization on their expensive GPU-goosed systems. They started to look at the pooling of memory and other kinds of accelerators, too, so GigaIO experienced “tremendous interest” in PCI-Express 4.0 fabrics — including a bunch of HPC centers, a slew of academic and commercial institutions, and two of the eight hyperscalers in the world (who were not named). The COVID-19 vaccines allowed people to get back into the datacenter and test gear, too.

Startups have to capitalize on such waves of interest, and that takes capital. And so the GigaIO board of directors gave Benjamin the go ahead to raise $10 million in a Series B funding round. The company got started with an undisclosed amount of seed finding from EvoNexus in June 2017, which was followed up in September 2018 with a $4.5 million Series A round from Mark IV Capital.

As it turns out, the appetite for investment for the Series B round was larger than expected, and GigaIO was able to take down $14.7 million in funding, with this round led by Impact Venture Capital and including participation from Mark IV Capital, Lagomaj Capital, SK Hynix, and Four Palms Ventures. Benjamin says that with FabreX orders and shipments at an all-time high, it could have taken a lot more money than this, but the board was not willing to sell more shares at the current valuation and would get enough money to take GigaIO to the next level, raising its valuation and allowing it to raise a much bigger chunk of cash down the road to push the business even harder.

The main drivers for GigaIO at the moment are that companies want to have variety and composability for the interconnects that link accelerators to servers, and they also want to drive up utilization while at the same time being able to precisely tailor the ratios of compute engines for specific work.

“In almost all of the conversations we are in, customers are telling us they want variety when it comes to accelerators,” says Benjamin. “They want A100 GPU accelerators from Nvidia, but they also want A6000s and they want FPGAs and they want custom ASICs. They want to run different jobs — or different parts of a workflow — on different accelerators. And that includes the hyperscalers, too, who are telling us that they are not getting anywhere close to the utilization levels they want to see on their GPUs.”

In the future, particularly with PCI-Express 5.0 switching and the CXL protocol, the conversation is going to shift hard to memory pooling, says Benjamin, who has been waiting a long time for this moment like the rest of the system architects in the world.

“Everything we already do in PCI-Express we will be able to do with CXL, which is a much leaner and meaner protocol that uses the PCI-Express hardware for a transport but which replaces the PCI-Express protocol,” explains Benjamin. We have seen the same thing coming, calling it a memory area network in reference to the memory sharing that IBM is offering with its Power10 processors. But in the case of CXL it is probably even more accurate given that the memory pools will be like the storage pools that were aggregated and partitioned to drive up utilization on what were called Storage Area Networks, or SANs, which were linked to servers in a shared fashion using Fibre Channel interconnects.

“CXL is going to be really helpful in this regard,” Benjamin continues. “Accelerators are really interesting to a certain set of the population, and we can argue if HPC and AI are 25 percent or 50 percent of the datacenters. Artificial intelligence is certainly helping the case for disaggregation and composability. But at the end of the day, the real prize, the ultimate in terms of composing, is memory. That opens up every single workload in the datacenter.”

This is certainly part of Intel’s thinking with CXL, as the company showed in a recent presentation at Hot Interconnects. CXL could become the memory controller on processors as well as a CPU-to-CPU interconnect in the long run, and many of you commented to us about that after reading the story. Moving from asymmetrical to symmetrical caching is not that hard, and it could be a special superset of the current CXL.

Which brings us back to a point we have made several times now. If PCI-Express is going to be a fabric interconnect to lash together pools of CPUs, DPUs, GPUs, FPGAs, custom ASICs, storage, and memory, then someone is going to have to provide hypervisors to manage the virtualization layers here. We already have the means to manage virtual CPUs, GPUs, and storage, but no one as yet has created a memory hypervisor that will span local, near, and far memory banks across several racks — or maybe even a row — of machinery. But the need will be there for this.

MemVerge has created the closest thing to a memory hypervisor that we have found, and it would be very interesting to see GigaIO and MemVerge get together in some fashion to create a more complete hardware/software stack. The companies could just merge instead of trying to eat each other and waste a lot of money and time, and then get to work building this memory pooling stack.

It also strikes us that if Nvidia doesn’t support CXL on the PCI-Express variants of its GPU accelerators, and Intel and AMD do, then companies might find that NVSwitch is a bit overkill and limited in scale (only eight GPUs in a pool) and that for certain workloads using CXL over PCI-Express 5.0 will be tight enough memory coupling between GPUs and between CPUs and GPUs for AI and HPC workloads.

Full coherence might be overrated, as Ralph Wittig — the chief technology officer at Xilinx and one of the proponents of the CCIX interconnect — once aptly reminded us over lunch two years ago. Everything has its place, but having slightly looser coupling to provide greater sharing and greater scale might be more important in the datacenter of the future.

Be the first to comment