Watching Amazon Web Services explode on the scene and grow to ginormous size has been a thing to behold. While we believe that a return to utility computing was inevitable because of the economics of large scale computing – and we believed that a long time before AWS was launched in March 2006 – we would be the first to admit that AWS was the first to really have a vision for what we now call, somewhat stupidly, cloud computing. There’s nothing cloudy about it at all, if you think about it.

As we have pointed out before, what Jeff Bezos & Company have built, initially just to offload some of the cost of its own IT expenses for its Amazon online retail business to customers who could rent its spare capacity, is nothing short of the world’s largest multiuser system. It is in reality everything that a modern mainframe could ever dream of being, with an ever-embiggening array of new features, functions, and services being added to the stack at a rate that no one has been even close to match. Well, Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud are giving it a run. But we all know who is winning the race.

But the IT sector doesn’t really like monopolies, and there was never any way, ever, that AWS would enjoy the kind of near-monopoly control that IBM had in the datacenter in the 1960s and 1970s or Microsoft had on the desktop in the 1990s. Markets like at least two or three options, and therefore AWS was always going to be limited by that sheer fact. Microsoft was always going to have a big Azure business as long as it converted its vast Windows Server base and Windows client base to use Azure services. Which it has certainly and successfully done. Google, just by virtue of having built some of the best IT infrastructure hardware and software ever designed by humans and running it at scale for its own businesses, was always going to get its share. And in China, Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu were always going to get their share, too.

But there are limits. There is only somewhere on the order of $210 billion spend on datacenter systems and $510 billion spent on enterprise software, plus another $1.09 trillion spent on IT services worldwide in 2020, according estimates made by Gartner. So the total addressable market AWS and other cloud builders was always set at somewhere around $1.4 trillion. The piece that AWS is targeting is really only about half of that, we reckon. A lot of that spending in those Gartner figures goes into building the hyperscalers and big public clouds themselves – call it half – so that’s on the order of $360 billion right there, with somewhere around $100 billion of that being for datacenter systems. And the fact that AWS closed out 2020 by pushing $45.73 billion in services – and somewhere around $27.5 billion of that for core compute, storage, and networking services – shows just how much spending that would have been done by customers has been displaced. Clouds create demand for infrastructure through their ODMs and destroy business that OEMs might have done with enterprises, but then enterprises turn around and rent the capacity. To really figure out the effect that clouds like AWS have had on the market, you need to see all the IT budgets in the world and what percent is spent on premises and what is spent in the cloud, not look at IT vendor factory revenues. The market researchers count things in a way that sounds precise, but we can’t really tell what is actually going on.

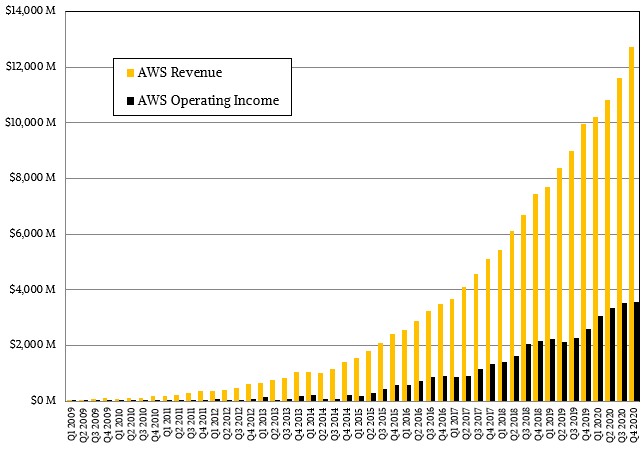

The revenue and operating income at AWS tells part of the story, of course:

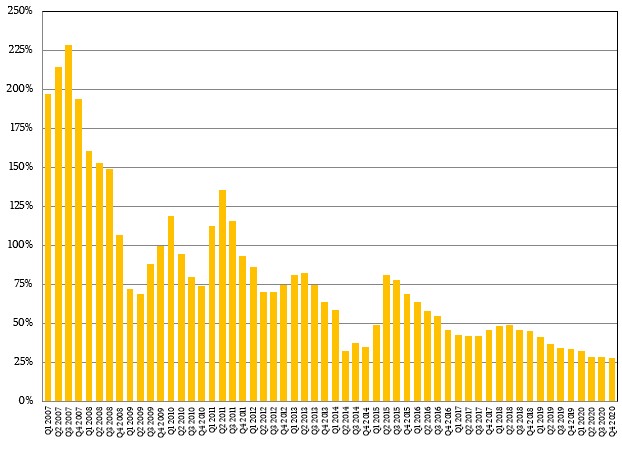

But only part of it. Let’s take a look at quarterly revenue growth since AWS started.

We can see the interplay of the attractiveness of the utility computing model – you rent only the capacity you need, and pay a premium per clock cycle or bit moved or byte stored over buying it yourself, but you don’t have to shell out the capital to buy the gear or build the datacenter yourself – and actual recessions in the economy. Look at 2009 in the revenue growth chart above. But also, you can see the general effect of the self-imposed recessions that AWS sustains hits from as it proactively and automatically cuts prices on its infrastructure services over time to help keep competition at bay and customers happy. This is very smart, but doesn’t generate as much cash in the short term as, say, traditional IT vendors who tend to gouge captive customers, nit cut them a break.

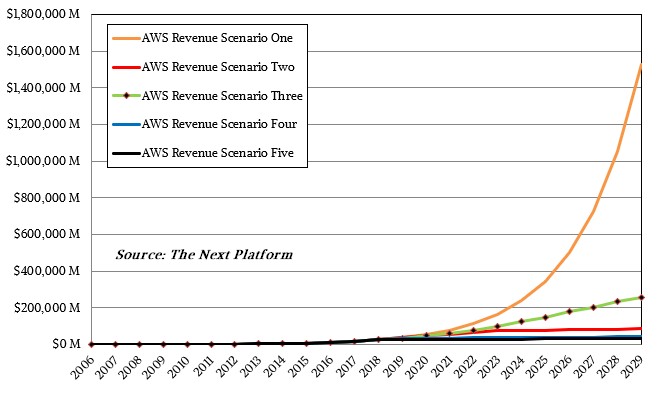

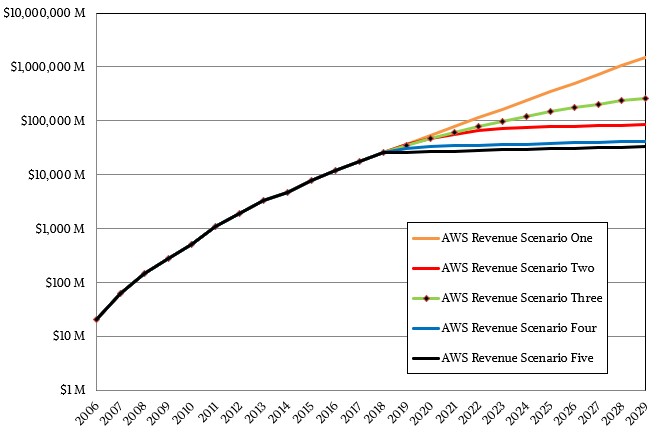

What we can also see, and what we talked about in detail back in February 2019 when we built a revenue model for when AWS would break through the $100 billion barrier, is that growth is slowing for AWS, and at a rate that is consistent with all upstarts in the IT sector. At the time two years ago, we reminded everyone of the limits of large numbers effect and that there were limits to the size any cloud could be, and showed scenarios where AWS just kept growing at the pace it was setting two years ago, or dropped down to a meager 2.5 percent growth rate to match global gross domestic product, and a few scenarios in between. Here is the chart from two years ago showing the possible scenarios:

And here is the same chart on a log scale to make it easier to see the differences in the scenarios:

We said then that the most likely path that AWS financials would take was somewhere between Scenario One and Scenario Two, which have growth rates that decrease over time and then stabilize at somewhere around double that of GDP growth for a while before just humming along at GDP growth rates well into the future and much further out than this forecast. As it turns out, with $35.03 billion in sales in 2019 and $45.37 billion in sales in 2020, the top line at AWS is tracking just a little behind Scenario Two. And that means AWS should be larger than the IBM that is left after it spins off its managed services business into NewCo this year (leaving Big Blue at around $59 billion in sales) by the middle of 2022 and depending on how it grows from there AWS could break through $100 billion before the end of the decade.

There is a reason that Amazon co-founder and chief executive officer Jeff Bezos is handing the reins to AWS CEO Andy Jassy, who is to become CEO of all of Amazon in the third quarter of this year as Bezos becomes executive chairman of the company, focused on special projects, while at the same time pursing his ideas about the press through his ownership of The Washington Post and about the commercialization of space through his ownership of Blue Origin. Creating Amazon and AWS has made Bezos the richest man in the world. Not bad for a guy who wanted to create an online bookstore to give Barnes & Noble hell. Bezos is shaking up four different industry segments with the wealth he created – often defying gravity of the financial type because, let’s be honest, the e-tailing business, while large, is a tremendous pain in the ass. AWS was the smartest thing Bezos ever let happen, and that is because IT vendors were even more sluggish than retailers, and had higher operating profit margins – like an order of magnitude higher. All of them saw the utility computing wave coming, someday, and Bezos jumped into the pool and created a huge wave that has swamped them all.

But, as we say, there are limits to growth here, as there are in all ecosystems. Take a look at the revenue growth chart above again, which shows AWS quarterly growth rates since Q1 2007, a year after the S3 storage and EC2 compute services first debuted.

In its first year of sales, we reckon AWS did something on the order of $21 million in sales, so to crest above $45 billion – a factor of 2,184X growth over those 14 financial years – is astounding and demands our respect. AWS is a tremendously diverse timesharing system that spans the globe and that has millions of customers and probably many billions of users hitting applications on it.

In the fourth quarter, AWS posted sales of $12.74 billion, up 28 percent year on year, with operating income of $3.56 billion, up 37.3 percent. For all of 2020, sales were, as we said, up 29.5 percent to $45.37 billion, and operating income was up 47.1 percent to $13.53 billion. Operating income is averaging somewhere around 30 percent of revenue, which is decent. AWS averaged about 11.8 percent of total Amazon revenues in 2020, but accounted for 59.1 percent of Amazon’s operating income. It is safe to say that without the AWS launch, Bezos would not be the richest man in the world and Amazon itself might not be anywhere near as big as it currently is. And we think it will be a cold day in hell when AWS spins out as a separate company from Amazon. The retail business needs the profits from the IT business to allow it to grow, to build the substantial warehousing, trucking, and air freight divisions that will drive Amazon’s future growth in retail.

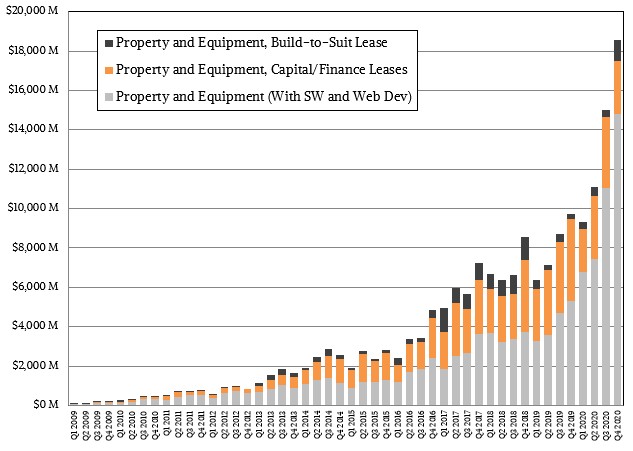

If there is no way in hell that Amazon will ever separate from AWS – which explains in part why Jassy is moving on up to take over all of Amazon and will one way or the other keep a tight rein on AWS, which he helped create – then there is no way in hell anyone can start today and build a business that can ever hope to compete with AWS. Just take a look at the capital expenditures Amazon has shelled out over time:

That chart just blows our minds. Amazon spent nearly $54 billion last year on property and equipment, and has spent $186.8 billion since 2006. The spending is going way up, and if about half of that is AWS infrastructure, this is a tremendous IT budget – and one that few companies can match. Google with its advertising business and search monopoly and Microsoft with its vast Windows monopoly and Windows Server business are two that can play the game. Few others on Earth, short of national governments, can play at this level.

Amazing.

Be the first to comment