Compute drives supercomputing, and networking is the chassis and storage just comes along for the ride. Processor upgrade cycles are the boon and the bane of the existence of all system suppliers, and supercomputer maker Cray is no exception. The timing of the launches of its own processors in the early days and of AMD Opteron and Intel Xeon processors in more recent years has had a dramatic affect on its prospects for any given year.

Just as the supercomputer market has contracted – Cray thinks by as much as 60 percent compared to the peak levels that it saw between 2015 and 2017 – there is a proliferation of compute architectures available on the market at the same time that Intel, the dominant supplier of compute engines for Cray’s CS and XC lines of systems, is having difficulty with its 10 nanometer manufacturing processes and therefore is rewriting all of its server roadmaps. HPC centers want to be on the leading edge of technology, and so when there is a stall in deliveries that dulls the edge and they get cranky. Understandably so.

This happened with AMD’s “Barcelona” Opterons with Cray back in the summer of 2007 with its XT4 systems and the “Gemini” interconnect. This delay caused Cray to abandon its architectural marriage to AMD’s HyperTransport bus, which was extended from CPUs and memory to the Gemini interconnect, and opt for a more generic PCI-Express link and, as a bonus, adopt Intel’s Xeons as the compute in its top-end XC systems and their “Aries” interconnect. (Which Intel has owned since 2012, by the way.) Now, with the future “Shasta” systems coming down the pike next year, we think Cray will open up its compute options, especially since Intel cannot get the 10 nanometer “Ice Lake-AP” Xeon processors aimed at the HPC crowd out the door until the middle of 2020, and the 14 nanometer and multichip “Cascade Lake-AP” is not expected until the middle of next year for first shipments to vendors and probably months later to customers in systems like Shasta.

Cray is keeping its cards pretty close to its chest about what its future processor plans are for Shasta, but it has adopted Cavium ThunderX2 processors in XC systems with Aries interconnects and AMD Epyc 7000s in CS-Storm clusters that have Omni-Path, InfiniBand, or Ethernet interconnects. It stands to reason that Shasta will have a more open attitude about interconnects and compute. The company has to balance adding more complexity to its product line – and therefore having a much broader matrix of components to test and support – against the risk of having products come to market late. To be blunt, Cray is already hurting this year from the cancelation of the “Aurora” pre-exascale system at Argonne National Laboratory, which was slated to be installed earlier this year. Intel was the prime contractor on the Aurora deal, with Cray providing the system that was to use Intel “Knights Hill” Xeon Phi parallel processors, etched with 10 nanometer process, and “Apple River” 200 Gb/sec Omni-Path 200 Series switches, presumably not dependent on that process or we would not see it until late 2019 or early 2020 at the earliest. (We know that Omni-Path 200 is coming next year.)

This Aurora machine was supposed to be the first Shasta system, and Cray’s numbers for the quarter just ended would look a lot different if Aurora had been delivered as planned.

Argonne is working with Intel to deliver the “A21” exascale system to Argonne in 2021, which it has divulged some details of. But on a conference call with Wall Street analysts going over the second quarter numbers, Pete Ungaro, Cray’s chief executive officer, said that Intel and Cray are working with Argonne on this A21 machine, but the contract had not been signed as yet and added that he could comment beyond what the US Department of Energy, which is paying for them machine, has already divulged. (We would have thought that Argonne would have signed the deal with Intel before talking about the system.)

Cray Wants Its Cake And Icing, Too

Cray is in a funny place in that it wants to get revenues back to where they were a few years back, but it can’t count on exascale systems to get there because of the political and capricious nature of those deals. It is not possible for Cray to win exascale deals in China or Japan because those countries want to pick indigenous suppliers, and Europe really wants to do the same thing as it is trying to cultivate homegrown processors, interconnects, and system suppliers. (Cray’s embracing of Arm processors this year in its XC line is a hedge and a wedge to try to win some big European deals down the road.)

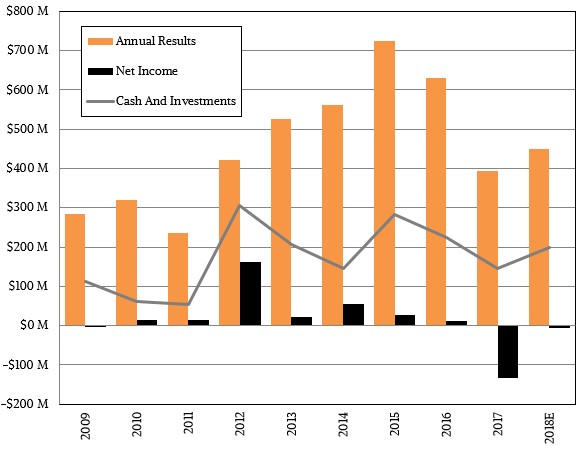

“We are seeing the market rebound,” Ungaro said on the call. “And we feel very confident that the market rebound is going to continue and get back not just to where the market was, but even beyond where the market was – and that is not including exascale. I like to think about exascale as kind of icing on the cake versus the cake. And with the market, the general market being the cake and so, we really just need to see that market continue to grow and get back to the size than it was.” This is where Ungaro repeated that the market had contracted by 60 percent from the peak a few years back, and Cray is down 46 percent from its peak of $724.7 million in 2015 to its low of $392.5 million in 2017. If the year plays out as expected, with around $450 million in sales, then Cray will only be down 38 percent – significantly less than the contraction in its key supercomputing market.

That is a kind of winning, if you think about it.

But we want a real win. Cray clearly needs to make more inroads into commercial entities, and a revival in the energy sector, which is finally underway as the price of a barrel of oil ascends, is only part of it. Cray’s plan is for commercial companies – aerospace, energy, financial services, manufacturing, and so on, not the big government and academic supercomputing centers – would comprise 15 percent of its business in 2018. It is a little bit under that level in the first half of this year, but the pipeline for commercial business is building. The key, we think, will be to provide truly scalable machine learning systems that will appeal to enterprises that want to mine their vast stores of data. The upshot is that the same machines that can be used to do machine learning can also be used to do traditional HPC – and that will have to be the same pitch.

The good news for Cray is that its pipeline of bids is about 3X larger than it was a year ago, and Ungaro explained that pipeline was not an issue even during the downturn. The potential deal pipe was always pretty full, but it just wasn’t moving. Now, the pipe is bigger and it is moving, albeit not fast enough for the company to break through $1 billion in sales as it clearly wants to do.

The quickest way for Cray to do that might be to engineer a merger with Mellanox Technologies and own its own interconnect future once again. (Mellanox could buy Cray and take the Cray name, much as Tera Computer did back in 2000.) For all we know, Cray is working on a new generation of interconnect, or a collection of them, for the Shasta systems. We hope so. We like a Cray that does its own interconnects. We would like one even better that could do its own CPUs, but that is a lot to ask for. But, we are asking, it looks like.

Mellanox is going to break $1 billion in sales this year, has a market capitalization of $4.25 billion, and has $282.6 million in the bank. Cray has a market capitalization of $965.7 million and we guess it might have $200 million in the bank as the year ends if all goes as expected. Mellanox paid $811 million for EZchip, the basis of its BlueField parallel Arm processors, and it might have to pay $1.2 billion to $1.5 billion for Cray. A merger between Mellanox and Cray would make about half of the combined $1.5 billion in sales commercial and the remaining half coming from traditional HPC centers in academia and government, we estimate. That is one sure way to blow through that 30 percent goal Cray has for its supercomputer business. This would, of course, make Mellanox a competitor to some of its HPC customers, but with the BlueField processors, Mellanox is already starting to compete with some of its storage customers and by definition the offload model Mellanox has championed takes away cycles from the CPUs in the systems so it has always been at odds with Intel, AMD, IBM, and others. This is the way of the world.

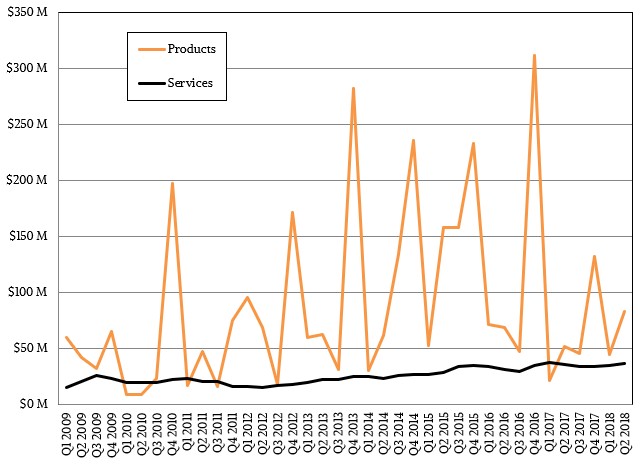

Here is another way to look at the situation. Nvidia has been selling DGX-1 and now DGX-2 systems for the past two years, and these HPC and AI servers now drive about 15 percent of the $2.8 billion datacenter business at Nvidia. That is $420 million a year at the current rate in DGX sales; Cray will probably do maybe $300 million in product sales in 2018. Nvidia has a larger system business than Cray, and Cray has systems that scale a hell of a lot further than the DGX line – unless you network them with InfiniBand. And by the way, the gross margins on that DGX-2 are a lot higher than on a CS-Storm, we think. Our point is, it is time for Cray to get creative. Nvidia did and it is without question eating into its supercomputing space, and it will do so even more in the coming years.

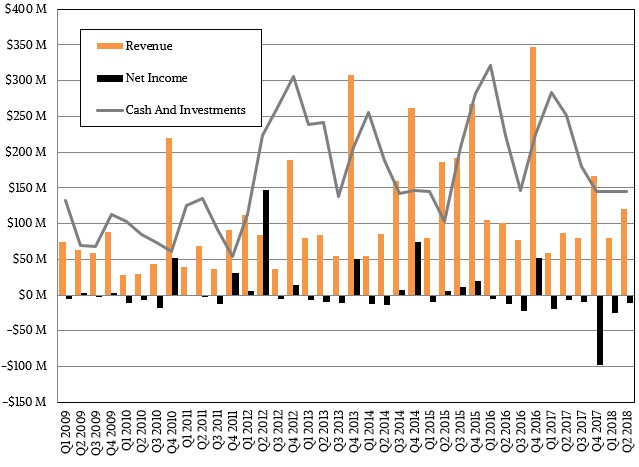

In the quarter ended in June, Cray posted sales of $120.2 million, up 38 percent, and it booked a loss of $11 million, higher than the $6 million it lost in the year ago period. The company exited the quarter with $144.3 million in cash. Brian Henry, the company’s chief financial officer, said that Cray expected for the company to have around $90 million in sales in the third quarter, which would be 13 percent higher than in Q3 2017, and with full year sales estimated to be coming in at $450 million, that implies sales of $160 million in the fourth quarter, down 4 percent. Henry added that Cray did expect to report a loss for the quarter. We have taken our stab at the numbers below, which are for full years.

As we have said before, Cray really needs to be evaluated on an annual and generational basis, not quarterly, because of the lumpiness of the HPC sector. Hyperscalers and cloud builders are no less bumpy in their spending. The trick is to have all three so the curves smooth out a bit while growing steadily.

This brings us to our last point. AMD has been in the dog house with Cray since the Barcelona Opteron delays wrecked its financials in 2007 and 2008. But maybe, with the Epyc chips offering very competitive band for the buck, it is high time that Cray adopt AMD chips once again in the XC series – particularly with AMD looking to get the upper hand on Xeons with the “Rome” chips due next year. It wouldn’t hurt for AMD to have a Radeon Instinct GPU accelerator that had some double precision and half precision and dot product math to compete well against Nvidia’s “Volta” GPUs, too.

So many possibilities, so much fun to have. . . .

Just between you and I, if they went Epyc, the Chinese could add their own unembargoed Epycs.