The server market has been spoiling for a fight for so long that it is hard to remember a time when there was intense competition across multiple processor vendors and architectures. But we have long memories, as many of you do, as well as long time horizons looking out into the future. Finally, there is a real fight for the heart of compute in the datacenter, and there has never been a better time to be able to consider something other than a Xeon for a server.

The first round of that fight between AMD and Intel got underway at the hyperscaler datacenters this time last year, when AMD, after an nine year hiatus, launched its “Naples” Epyc 7000 processors ahead of Intel’s “Skylake” Xeon SPs. Now, we are well into round two, as the next tier of upstart web tech companies and HPC centers are starting to adopt Epyc systems, and round three will feature some fancy footwork, weaving, and bobbing as AMD squares off against Intel to take on the traditional, on-premises datacenters of the tens of millions of enterprises in the world. AMD is getting its products, roadmaps, and ecosystems together as Intel is faltering a bit, and the expectation is that the company will take a significant amount of market share in 2018 and even more in 2019.

The competition is stiff enough that Brian Krzanich, chief executive officer at Intel, reportedly told Wall Street analyst Romit Shah of Nomura Instinet that Intel was going to lose market share to AMD and added that it was Intel’s job to not let its long-time X86 rival capture 15 percent to 20 percent of the server pie. We presume that this is share based on shipments, not revenues, as is traditionally how share is gauged.

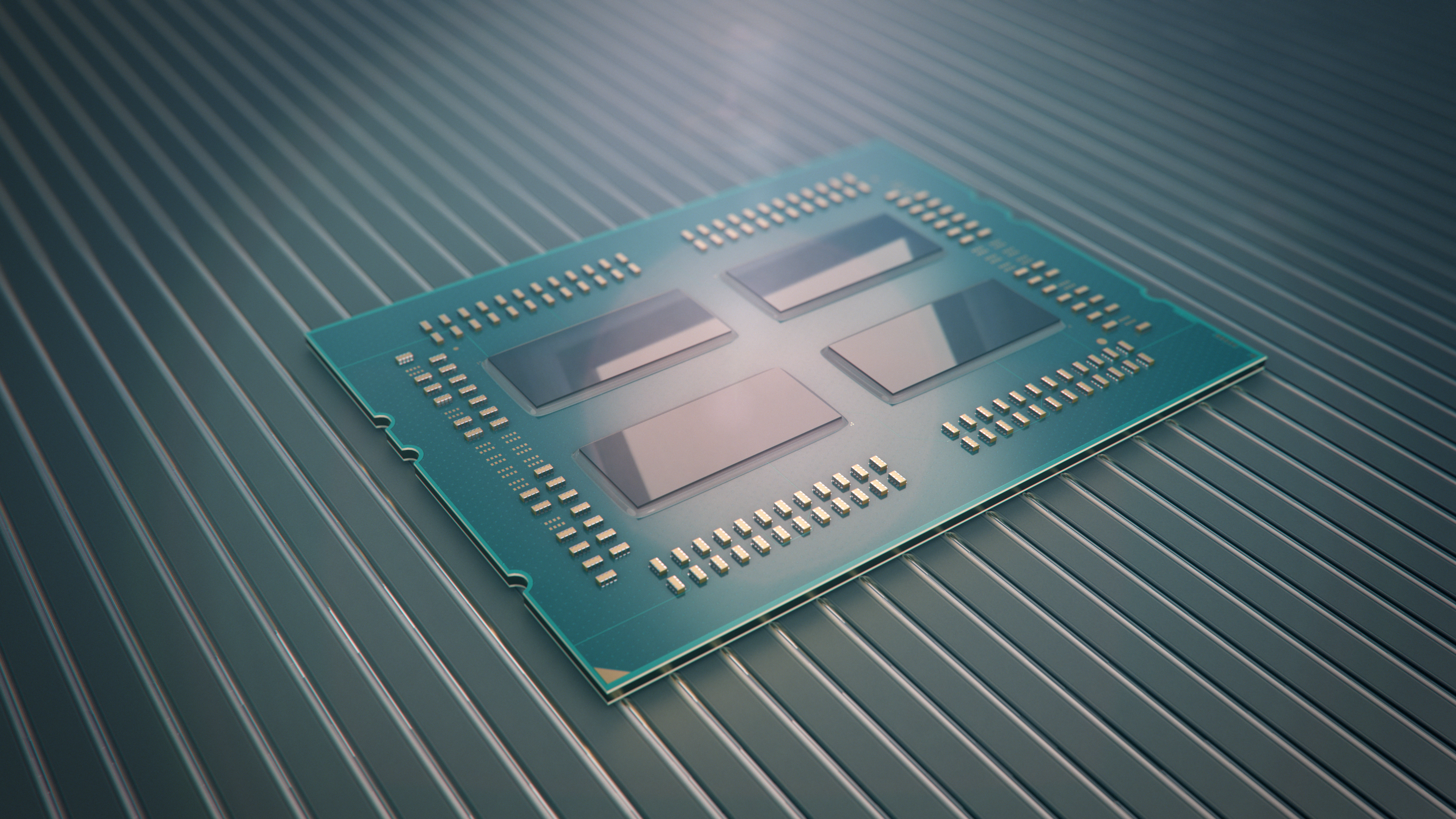

Given the history of the server racket, we think that maybe as little as 20 percent to perhaps as high as 30 percent of the annual shipments of machines are in play as companies – particularly the biggest buyers with the most leverage – are looking for ways to get a performance edge or price advantage. There are a lot of different platforms that are chasing the expanding server market, and that expansion has hidden some of the intense competition and has, frankly, taken some of the heat off of Intel. But that expansion is in part based on high component prices, as we have already explained, and the competitive pressure on Intel is only going to get more intense now that the company has delayed its rollout of future Xeons based on 10 nanometer processes. AMD, on the other hand, will be making the jump from the 14 nanometer processes used with its Naples Epyc chips straight to 7 nanometer processes with the future “Rome” Epyc processors, which are in the labs now, which will be sampling at the end of the year, and which will ship early next year.

Intel is going to have to do some pretty fancy footwork to keep up, and that will very likely mean mostly pulling down hard on the price lever. There is plenty of headroom in the Skylake Xeon list prices to do that, of course, but street prices will have to come down to compete against not only the AMD Epyc chips, but also credible Arm processors, mainly the ThunderX2 from Cavium and the “Amberwing” Centriq 2400s from Qualcomm, which are both chasing the much-desired high volume hyperscalers and cloud builders. IBM will be picking off Xeons at the high end of HPC, machine learning, data analytics workloads with its current “Nimbus” and future “Cumulus” Power9 chips, too. But AMD, by virtue of having an X86 architecture, has the best chance of winning the business away from Intel in the core two-socket server business and what could finally be a viable single-socket server designed for real enterprises.

Getting Back Into The Ring

It has taken some time for AMD to find its way back to the datacenter. Taking on the hegemony of Intel and its vast ecosystem of ODMs and OEMs as well as shifting the established buying patterns of customers is no easy task. AMD knows this better than any other company, having successfully taken on and beaten Intel in the past with its “Hammer” line of Opteron chips, launched in April 2003 with much fanfare and excitement. The market was overripe for competition then, as it is now, and AMD brought many innovations to bear – 64-bit processing and addressing with an X86 instruction set, integrated memory controllers, HyperTransport links for NUMA shared memory, and an architecture designed to cookie cutter multiple cores onto a single die as manufacturing processes shrunk – to take on a stubborn Intel that was trying to keep Xeons at 32-bits (and therefore very small memories) and push customers to the Itanium architecture to get 64-bit processing and addressing.

Back then, the gap between the Xeon and the Itanium was big enough to drive a semi through, and this is precisely what AMD did. And not with just its first foray into servers, but its second attempt. Prior to the Opteron, AMD launched the Athlon MP, a beefed up desktop processor that was aimed at servers, a strategy that Intel had taken years earlier with its Pentium MPs until it broke the Xeons free and started designing specifically for servers, as its RISC and CISC processor makers did for their systems for decades.

“The Athlon MP did okay because people were using modified desktop processors in servers, but it was not the homerun product that Opteron was,” Dean McCarron, president of chip watcher Mercury Research, tells The Next Platform. “Opteron took a couple of years before it really saw traction. AMD’s share of servers was at about 5 percent in 2004, a year after launch, and it peaked in the middle of 2006 at around 25 percent.”

The reason Opteron did so well is that this was the beginning of the age of hyperscalers and cloud builders, and they have to do better than Moore’s Law improvements in price/performance to remain profitable as they expand their global footprints of immense infrastructure.

A decade and a half after the Opteron launch, the server market is very different. But it is reacting to the Epyc launch in a very similar fashion, and once again because of a thirst in the datacenter for an alternative CPU supplier with a different, rather than a clone, product and its own price curves to sweeten the deal.

McCarron says that AMD’s share of the server space hit rock bottom at the beginning of 2017, with a mere 0.3 percent of shipments based on the prior Opterons. McCarron says that in the wake of the Epyc launch, AMD was able to garner around 1 percent share in the first quarter of 2018, and even though the second quarter still not done, he is forecasting that Epyc volumes are on a power of 2 ramp and will double every quarter for a while. AMD has been very clear that it hopes to exit 2018 with 5 percent shipment share and then build to a respectable double-digit share – that can be anywhere from 10 percent to 99 percent, of course – in the years after that. McCarron says that 5 percent by the end of 2018 is absolutely doable.

“When we think about the ramp of Epyc, a few things stand out,” explains Scott Aylor, corporate vice president and general manager of the Enterprise Business Unit at AMD. “The first is that a really strong catalyst for adoption is that people now realize what life is like without us. There is the notion that when there is truly a single dominant player in the market, that’s really bad. And so there is a tremendous level of sponsorship and people are really pulling for us. There is also an element of credibility and trust. People really want us back, but some people will wait until the second generation is revealed. So there are some tail winds and some headwinds. In the Opteron timeframe, there were some similarities. We were a PC company, and there were some questions about what we knew about the server business. But the performance of Opteron was fantastic, and we had 64-bit processing and memory addressing and it totally changed the equation of what they could do.”

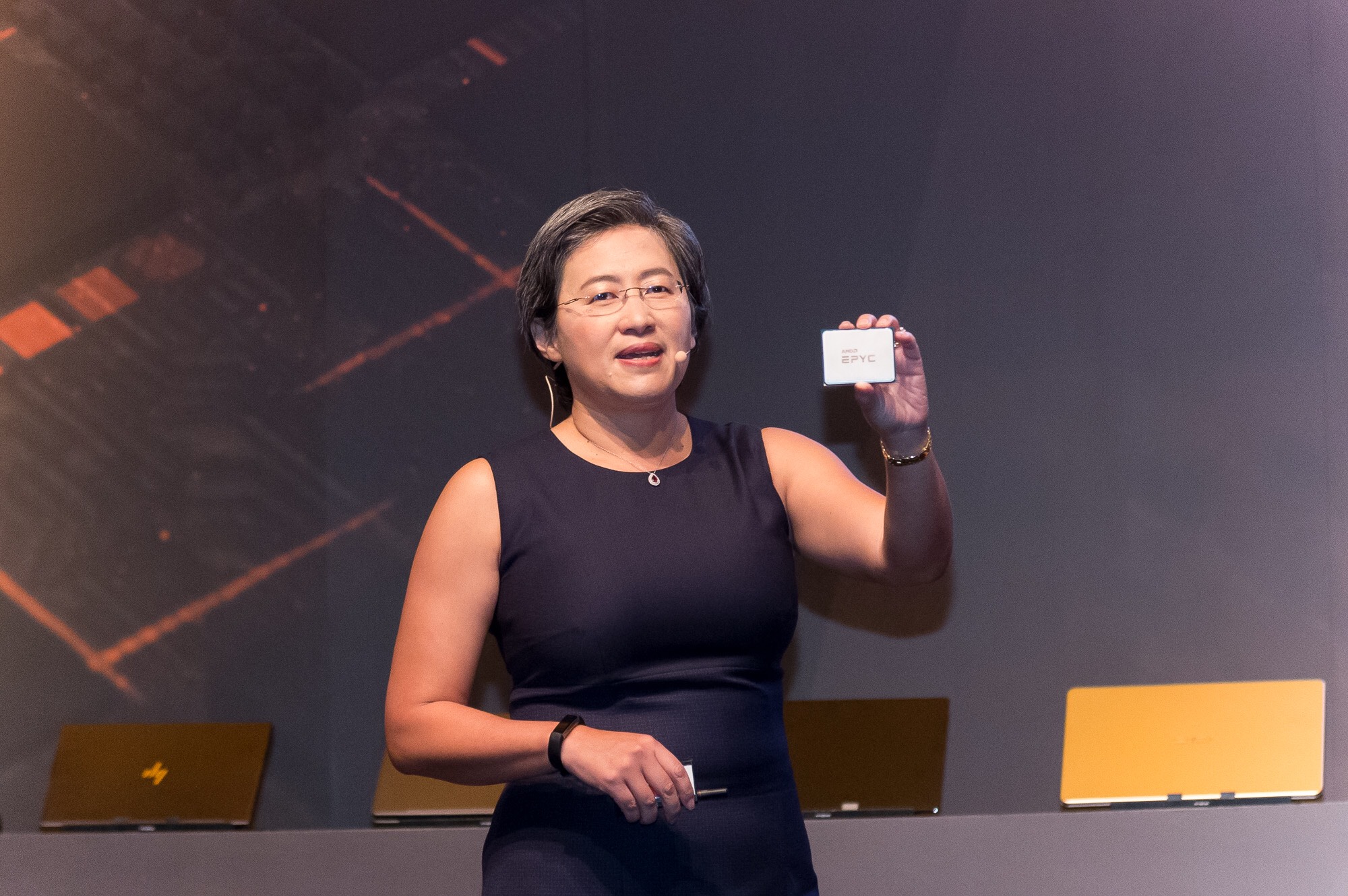

So a big part of the success of both Opteron and Epyc is simply creating a good chip and executing on a roadmap for future chips – something that AMD, quite frankly, struggled with at the tail end of the Opteron line with the “Dozer” family of chips that followed the Hammers. That is history now, the new management and design teams put together by AMD president and chief executive officer Lisa Su, are committed to the long term in the datacenter and are building the necessary credibility one chip and one customer at a time.

It all starts with a good foundation, and the Naples multi-chip module design allowed AMD to scale up its CPU while scaling down the cost, important differentiators in coming up against an Intel at the absolute peak of its game with the last three generations of the Xeon processors.

“If there is a clarion call to what happened last June, it is that we exceeded the expectations of the market,” says Dan Bounds, senior director of enterprise products at AMD. People should expect us to come back with a high performance CPU. We then came in with a CPU that exceeded the core count, radically exceeded the memory bandwidth, exceeded the I/O. That’s the first miracle. The second one is that we did that in the context of a one-socket platform, and customers can choose a one socket or a two socket – the latter being for the reason that they need it. Single socket is a place where Intel just doesn’t want to chase us.”

(We will be getting into the single-socket server value proposition in a separate follow-on story.)

It’s funny how these two rivals operate. Intel is a chip manufacturer first and a chip designer second, and AMD has traditionally been more focused on pushing chip design and then hoping that the chip manufacturing capabilities – either in its own fabs before it sold them off to GlobalFoundries or through its partners, GlobalFoundries and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp, after the spinout – can keep up. Intel is now the one struggling with manufacturing, and it looks like AMD has hedged its bets well with its 7 nanometer jump. Time will tell on that one, but AMD can get Epyc chips from either foundry if need be, , whichever one is yielding best as 2018 comes to a close and 2019 gets rolling.

The Terrific Ten Set The Pace

The server market has bifurcated quite a bit since AMD first came into the market with the Hammer Opterons a decade and a half ago, and perhaps no one knows this better than Forrest Norrod. Back in the early days of the Opteron, Norrod was an executive at Dell who started its Data Center Solutions custom server business, and a few years back, as AMD was getting serious about re-entering the datacenter, Norrod took the job as senior vice president and general manager of the Enterprise, Embedded, and Semi-Custom group at AMD that is spearheading that re-entry. Norrod has seen the server space as an OEM, an ODM, and a chip supplier now, and as such, he has wide and deep knowledge of the key groups of customers.

The most important ones when it comes to the adoption of new technologies in the datacenter are not the supercomputer set, as it has been in decades past, but the core hyperscalers and cloud builders – one of the central and founding themes of The Next Platform, in fact. The ten key hyperscalers and cloud builders now account for nearly 50 percent of server shipments, and the top three – that would be Google, Amazon Web Services, and Microsoft – together account for around 30 percent all by themselves and who buy millions – that’s million with an s – of machines each year. The biggest couple of the seven smaller hyperscalers and cloud builders – Facebook, Apple, Baidu, Tencent, Alibaba, and depending on who you ask Yahoo and China Mobile – acquire north of 500,000 machines a year, and the remaining companies are on the scale of 250,000 units a year.

“There are three distinct groups there in terms of volumes, but they all want to act the same way,” says Norrod. “And that cohort of ten, you have got to approach them with one model and then there is everybody else. With the Terrific Ten, I think the Epyc ramp has gone very well, and those guys are a little bit ahead. Our share would be slightly disproportionately skewed toward them. The HPC centers and next wave of web technology companies – think Dropbox and Yahoo Japan – are the next group, and it is ramping well. And finally there is the enterprise. In the enterprise, you are traversing not only a very complete OEM qualification cycle, but customers want to make sure you can run everything from the latest web services tool chain to Oracle RAC to that old Fortran compiler. We have been focusing more recently on the enterprise, and that is going nicely as well. We have recent Fortune 500 wins that we cannot discuss publicly, but this is ramping up nicely as well. They are sorted into those buckets based on their qualification cycles and the route to market you use to reach them.”

In some ways, the Epyc ramp has been easier than the Opteron ramp, and in other ways, it has been harder, Norrod concedes. Selling Epyc to the hyperscalers and cloud builders has been easier this time around than it was with the Opterons, he says, but getting Epycs into enterprises is taking a bit of effort. But the design wins at HPE and its partner H3C, Dell, Cisco Systems, Lenovo, Cray, Sugon, and Supermicro are going to be greasing the skids here, and the upstarts that play in the niches or build systems in volume for other companies, such as Quanta Computer, Tyan, Wistron, Inventec, ASUS, Gigabyte, AMAX, Penguin Computing, and Ciara, are going to reduce friction for Epyc adoption, too. And whether they know it or not or care or not, some customers will be using Epyc chips on the infrastructure clouds of Microsoft, Tencent, and Baidu and very likely on other hyperscaler and cloud provider services, even if those clouds or services don’t talk explicitly about the Epycs underpinning those services.

“When I get a substantive pushback, what I hear is one or two things,” Norrod explains. “First, they say Epyc is great, but not for their particular workload because an application can’t deal with NUMA affinity or they have lightly threaded workloads so ultimate single-threaded performance and high frequency is the most important thing. Or, they say that we blew it last time, and ask why they should have any confidence that we are not going to blow it this time. Having a demonstration of the roadmap is going to be critically important.”

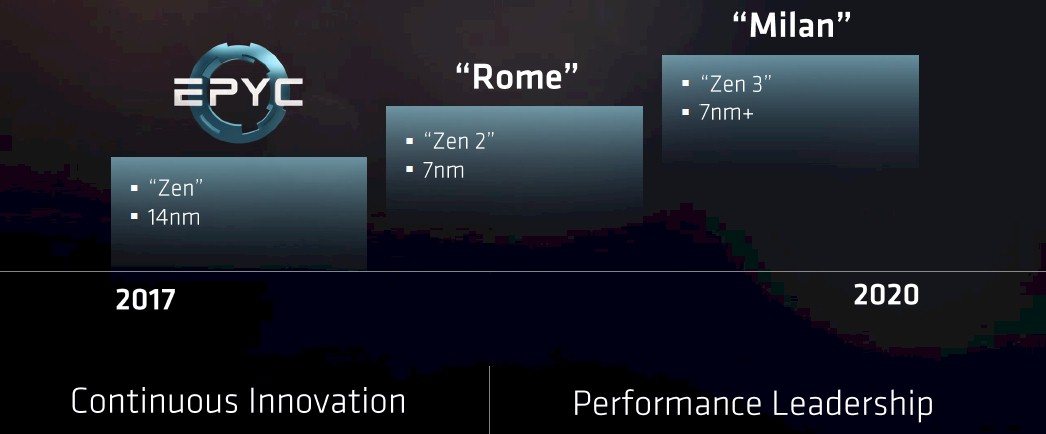

The AMD plan all along was for the Rome Epyc chip to come to market somewhere between 20 months and 24 months after the Naples Epyc chip, and then to get on a cadence of new chip launches every 12 months to 15 months under the assumption that Intel would crank out new chips like crazy and try to leverage its manufacturing prowess. This was Intel’s competitive response to the initial Opterons, and it wasn’t until nearly three years after the Opterons peaked in the middle of 2006 when the “Nehalem” Xeons finally came to market, and by then the Great Recession was roaring and AMD had botched the Dozer Opterons and it effectively left the ring.

The thing to remember, says Norrod, is that the first generation of Opteron chips got AMD that 5 percent market share, and it was not until it got a second chip into the fight that the share really started to take off. “Opteron really took off because it was more competitive, but even more important it came in when the water was fine and it demonstrated that AMD could serve the market. AMD is not just spoiling for a fight, but thinks it can land some more big blows.

“Our plan for the Naples-Rome-Milan roadmap was based on assumptions around Intel’s roadmap and our estimation of what would we do if we were Intel,” Norrod continues. “We thought deeply about what they are like, what they are not like, what their culture is and what their likely reactions are, and we planned against a very aggressive Intel roadmap, and I really Rome and Milan and what is after them against what we thought Intel could do. And then, we come to find out that they can’t do what we thought they might be able to. And so, we have an incredible opportunity. Rome was designed to compete favorably with “Ice Lake” Xeons, but it is not going to be competing against that chip. We are incredibly excited, and it is all coming together at one point. We have reintroduced ourselves to the market, gotten the initial traction and wins, we got the initial customer support, and we validated that AMD is a safe choice with an effective processor. With the Rome processor and process, we are going to be in an incredible position going forward.”

Your move, Intel. Just like we didn’t want to write Epyc Fail as a title for Naples chips, we don’t want to write Cascading Failures as a title for the future “Cascade Lake” Xeons being etched with an enhanced 14 nanometer process and delivered in the second half this year. It is the competition that keeps this server racket interesting and healthy, and Intel will have to weave and bob a little harder to land some punches on AMD.

Great article – congratulations!

One question re: “(Rome)..which are in the labs now, which will be sampling at the end of the year, and which will ship early next year.”

I don’t recall hearing that it will ship early next year and given that it will sample late this year, H2/19 feels more likely – even Q4/2019. What are you basing your statement on?

Thanks, again for a great article.

Epyc channel market share 4 this wk.

All volume shares r n relation unless said mkt share.

10% of Xeon Gold and adding Platinum 7%.

Epyc 32C in relation to Platinum 28C is 74% in relation that is 27% channel volume mkt share

Epyc in relation 2 all XSP 4 the wk is 5% as I have reported for several wks.

Adding all E5 v4 in the week, Epyc is 0.003% in relation.

All Epyc in relation XSP 28/26/24C is 32%.

Free u’r self from industry group think. See Bruzzone Seeking Alpha Blog posts; Views of Monopolization, Intel quarterly inventiry and Bruzzone tNP posts 4 real time data that does not tow the line 4 industry hand outs.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing

An excellent article.

Intel CEO resignation may have indeed a link with the Epyc story that is perfectly underlined in this excellent article 🙂