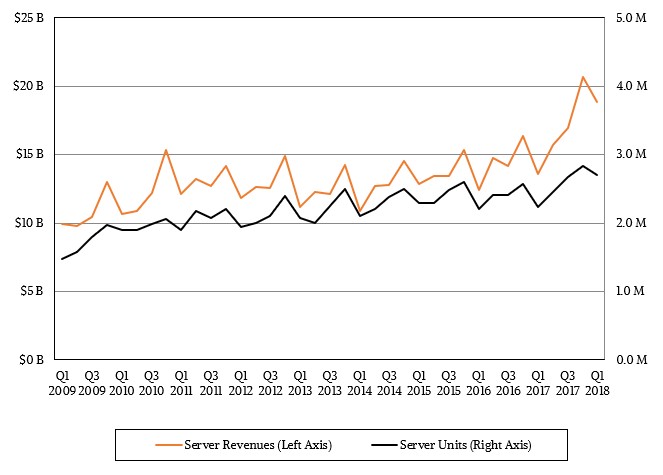

On the face of it, if you just look at the top level numbers, the server market is booming like we have not seen since the recovery in the wake of the Great Recession for a few quarters here and there between late 2009 and early 2011. That recovery was a bit spikey, but this one appears to be roaring steadily and increasingly louder. But don’t get too excited.

Some of this explosion in demand is indeed driven by the expansion of infrastructure, particularly among hyperscalers and cloud builders, which is exciting to be sure. But the big revenue bump is also being driven by more expensive Xeon processors, substantially higher main and flash memory prices, and richer configurations that have GPU and sometimes FPGA accelerators in them. And in all of these cases, the revenue bump does not necessarily mean server makers, whether they are traditional OEMs or upstart ODMs, are making any money from all of this revenue.

In fact, as memory and flash prices started to climb in late 2016 and then rocketed up in 2017, vendors tried to eat most of that price increase so they would not crimp demand. This was extremely painful for them, and in recent quarters we have seen how vendors have gradually pushed up the throttle on their memory prices, passing more of the cost onto buyers even as prices are starting to level out a bit. GPU accelerator prices have rocketed up 75 percent or so in the past year, as we have discussed, mainly because of cryptocurrency mining but also because of the demand for GPU compute for machine learning and, to a much lesser extent, HPC simulation and modeling jobs. With data growing and more and more of it being housed on server-based, software-defined storage, organizations can only hold back the spending for so long, and it looks like starting in the third quarter of 2017, the damn started to break. Add up the underlying current of increasing server demand (which is actually itself accelerating) to the increases in prices for components, and it is no surprise that the server market is going through the roof. Which it certainly is now doing.

But again, it may be only the semiconductor makers who manufacture the CPUs, main and flash memory, and GPUs and FPGAs as well as Microsoft and Red Hat, who supply the bulk of commercial operating systems for those who pay for support, that are actually bringing very much money to the bottom line. As far as we can tell from the numbers of Hewlett Packard Enterprise, servers are not a particularly profitable business once you take out the operating systems and support contracts, maybe 1 percent or two percent of revenues come in as operating margin. Dell, which has become both the dominant shipper and revenue generator from servers in the world, bypassing HPE, might be doing slightly better in terms of profitability, but that doesn’t mean that the ODMs, who work for a few pennies on the dollar and who basically have control of servers at the hyperscalers and cloud builders, have not put tremendous pressure on revenues and profits at all of the OEMs.

If there is a tougher market than bending tin to make servers, we don’t know about it. It’s still fun, and vital to the global economy. We ain’t bored, even if we do sometimes get nervous about the economic viability of it all.

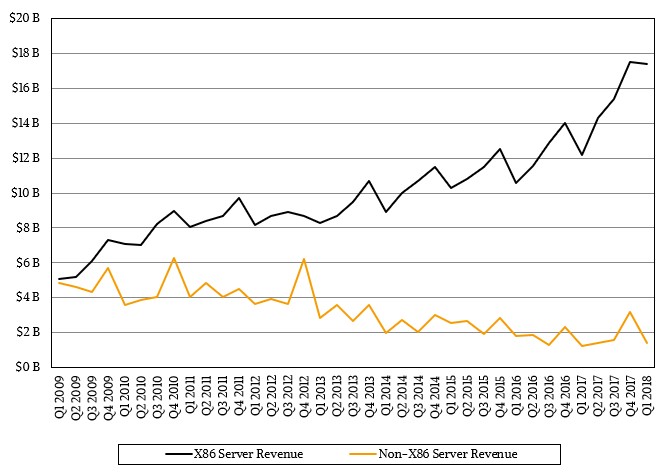

In the first quarter, the box counters at IDC, the world consumed just a hair under 2.7 million servers, an increase of 20.7 percent over the prior year’s quarter, and when the money was added up across the OEMs and ODMs, the revenue generated for all of those machines was $18.82 billion, up a stunning 38.6 percent year on year. This is the seventh quarter in a row for double digit revenue growth and the third quarter in a row for double digit shipment growth in the server racket, which is definitely a sign of the expansion. The X86 portion of the server market is the main driver for revenues (but certainly not for profits, which are still driven in large part by IBM mainframe and Power systems and a handful of other RISC/Unix boxes that are still sold), and in the quarter sales of X86 iron accounted for 99.4 percent of shipments and, at $17.4 billion in total across all manufacturers, had an amazing 41 percent revenue growth.

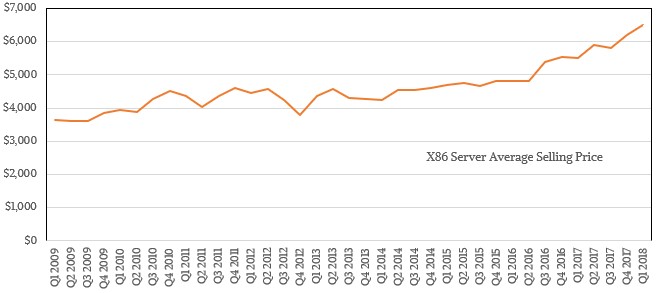

We reckon about half of that growth is just from the increase in component prices and the richer configurations of compute (either central or accelerator) that are being acquired. If you look at X86 average selling prices over time, you can see the spike:

If you go back to the first quarter of 2009, which was pretty much the bottom of the Great Recession and also when the transformative (and Opteron-like) “Nehalem” Xeon processors were launched, the average X86 server cost $3,643. That price kissed $4,000 in 2010 and then finally broke through as the rebound came. Average server prices have wiggled between $4,000 and $4,500 for many years, depending on how many servers and what kinds of configurations the hyperscalers and cloud builders installed, and for the longest time, the ASPs for these organizations were a lot lower than for the rest of the market. Since the advent of heavy configurations using lots of memory, flash, and sometimes FPGAs and GPUs, average selling prices of the ODM manufacturers that IDC tracks have been higher than the X86 market at large, and the rest of the market is now catching up. This is a classic scenario as far as The Next Platform is concerned. This is how it works. Back in the first quarter of 2016, the average ODM server cost $2,805, but the average X86 server (including the ODMs dragging down the price) cost $4,818. Fast forward two years, and the average ODM machine costs $6,648 and the average X86 machine costs $6,490. The hyperscalers and cloud builders, given their volumes, get a lot more machine for the money, to be sure.

As for the market outside of X86 machines, sales rose by 15.5 percent to $1.42 billion. The volume server segment, which is comprised of machines that cost less than $25,000 the way that IDC counts the boxes, rose by 40.9 percent to $15.9 billion. Midrange machines, which cost between $25,000 and $250,000, accounted for $1.7 billion, up 34 percent and was driven by high-end Xeon, IBM Power, and some IBM mainframe sales. The high end of the market, which is characterized as machines that cost more than $250,000, had $1.2 billion in revenues, up 20.1 percent.

We think the majority of this high end server revenue increase was due to the higher cost of memory and flash, and with some increase in compute costs added in. People are getting more compute with each generation, but the aggregate price of the system is still rising even if the cost per unit of compute is falling.

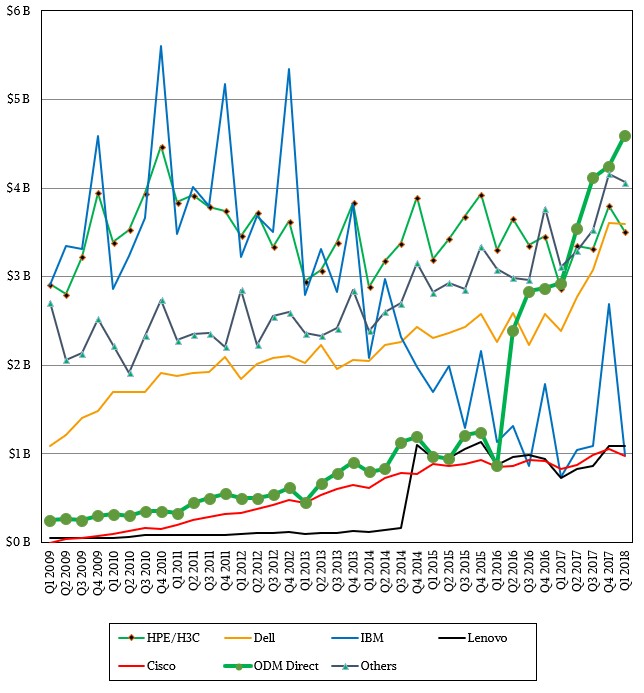

Dell has wanted to be the biggest maker of servers in the world since the late 1980s, when it first got into the PowerEdge business, and for the longest time, after buying Compaq, Hewlett Packard was able to hold the crown it had wrested from Big Blue. But unless something drastic changes, we think that Dell will probably remain the largest server maker until someone else comes along and topples it.

In the first quarter, Dell’s server revenues grew by 50.6 percent to $3.59 billion, and shipments rose by 18.9 percent to 555,800 units. If you add up HPE and its partnership with H3C in China, then this combo pushed 430,900 machines, down 6.4 percent, although with the increasing component costs that were passed through and the richer configurations, revenues still rose for HPE/H3C by 22.6 percent to $3.51 billion. Lenovo, which bought IBM’s System x business a few years back, had 50 percent revenue growth, helped in no small part to some big HPC deals, and posted $1.09 billion in sales against shipments of 160,700 machines, up 9.9 percent year on year. IBM had $989 million in total server revenues in the quarter, up 32.9 percent; shipment numbers were not available because IBM is no longer a top five shipper or an ODM. Cisco Systems had 18.8 percent revenue growth to $980.1 million and it was not a top five shipper, either. Supermicro and Inspur were, however, even though neither was a top five revenue generator. Inspur’s shipments in Q1 2018 rocketed up a stunning 77.5 percent to 175,000 units, blowing past Lenovo, and Supermicro increased shipments by 32.9 percent to 156,200.

The ODMs are tracked collectively as a group by IDC in recent years, and over the past few quarters the box counter has been revising its revenue numbers for this group. As best as we can tell from the quarterly updates that IDC puts out, the shipments it reckoned for the ODMs were right, but the revenue derived from these sales were too low. Hyperscalers and cloud builders were spending more on machines than IDC thought, and now this trendline is fixed. All told, the ODMs shipped 691,100 machines in the first quarter of 2018, up 55.8 percent, and that drove $4.59 billion in revenues, up 57.1 percent. Remember: Some hyperscalers and cloud builders buy from Supermicro, Lenovo, Inspur, Dell, and HPE, so it is not precisely correct to say that the ODMs own the whole upper echelon market. It would be great if IDC broke out server sales by customer set – the biggest hyperscalers and cloud builders, then other large service providers, then enterprises, and then HPC centers. We think we could learn a lot by seeing that trend data for the past decade.

Be the first to comment