It has been more than a decade since AMD was a force in computing in the datacenter. For that reason, we have not wasted a lot of time going over the ins and outs of its quarterly financials. But now that the Epyc CPUs and Radeon Instinct GPU accelerators are getting traction among hyperscalers, cloud builders, and selected enterprises, it is time to start keeping an eye on how AMD is doing financially.

With most of the financial analysis that we do here at The Next Platform, we use the middle of the Great Recession, in the first quarter of 2009, as the starting point. So many things were changing in the datacenter at that time – some of it driven by technology, some of it driven by economics – that this seems to be a natural starting point for the current era in computing. By that time, the Opteron server chips at AMD had peaked and the company had run out of roadmap to the future, basically ceding the server space to Intel’s Xeon line.

As we considered how far we needed to look back as a baseline for AMD’s numbers, we could argue that AMD’s turnaround in the datacenter started when Rory Read was brought in from Lenovo to run the company in August 2011, but the real changes that culminated in the current Epyc and Radeon Instinct products in the datacenter and the Ryzen and Radeon CPUs and graphics cards for client devices really started being refined when Lisa Su took the helm of the company in October 2014. To be blunt, AMD declined through the Great Recession and then, as far as the datacenter is concerned, lived through another self-made Great Recession between until a few quarters ago.

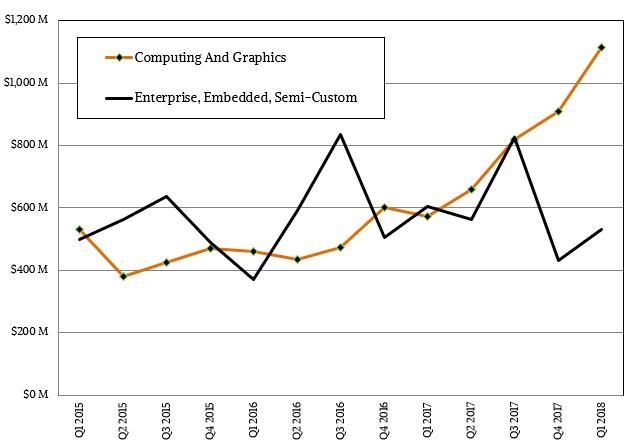

This is perfectly obvious when looking at the high-level numbers of revenue and net income, which are not very pretty from early 2015 through and the middle of 2017. Take a look:

To AMD’s great credit, it displaced IBM as the processor provider for the Sony PlayStation 4 and the Microsoft Xbox One X game consoles, providing custom CPUs and GPUs to both. Nintendo, which like Sony and Microsoft had used custom PowerPC designs from IBM for prior generations of game consoles, opted for a Tegra platform from Nvidia, which combines an Arm processor and Nvidia GPU, for its Switch console. AMD captured two out of three deals, and that was what has provided it with the fuel to create the “Naples” Epyc and “Summit Ridge” and “Raven Ridge” Ryzen CPUs and current “Vega” Radeon GPUs, which have varying degrees of applicability in the datacenter.

AMD was losing money throughout this period as it renegotiated its wafer supplies from GlobalFoundries, a chunk of which was its former foundry and it was investing heavily in the future desktop and server processors, including the “K12” Arm-based chip that has yet to see the light of day and that probably won’t unless someone pays AMD to build machines with it. While AMD was losing money through this period of engineering exertion, it managed to keep around $1 billion in the bank, give or take, which provided it with a cushion in case things got tight. And it cranked up the marketing machine, with gradual reveals about the “Zen” architecture for CPUs, building mindshare for the future X86 server chips, just like it needed to build mindshare with the original “Hammer” Opteron family in the early 2000s. AMD needed to repeat all the good things about its Opteron attack without making any mistakes, and against an Intel at the absolute peak of its game and market might and an Arm collective intent on trying to take share from any X86 chip supplier.

It is a good thing that Applied Micro, Cavium, and Qualcomm took so long to get their Arm chips out the door, that IBM was late with its Power9 processors, and that Intel charged premium pricing with its “Skylake” Xeons last year. This has given the market a chance to see if staying with an X86 architecture would be less grief for the same or better economics as moving to Arm or Power. AMD has done a very good job ramping up its PC processor and graphics card business, more than doubling it between early 2015 and early 2017 and almost tripling it as last year came to an end:

In a conference call with Wall Street analysts this week, Su said that the Ryzen products now accounted for 60 percent of client processor revenue, up from around 40 percent in the fourth quarter of last year, and average selling prices of the chips are on the rise. Part of this is due to the launch of the Accelerated Processing Unit, or APU, variants of Ryzen, which put Zen CPUs and Vega GPUs on the same package.

Gaming and cryptocurrency mining both helped pump up the Radeon products, too, which had better than seasonal growth. Su said that customers are testing the Radeon Instinct cards for machine learning workloads, and that it has the “Navi” kickers to the Vega GPU accelerators running on Instinct cards in the labs and will have them shipping in samples later this year. The Navi GPUs use the 7 nanometer processes from GlobalFoundries, a big shrink from the 14 nanometer processes used with the Vega GPUs, and not only will pack more punch but will have optimizations aimed specifically at machine learning. (We discussed the future Epyc and Radeon roadmaps back in June last year.)

Add it all up, and the Computing and Graphics division had 94.6 percent growth in the first quarter, hitting $1.12 billion in sales. Importantly, vitally, and thankfully, this business posted an operating income of $138 million, which works out to 12 percent of revenue and which is a pretty good profit for anyone peddling hardware, not just AMD. The shortages in the graphics card business are helping AMD, even if they seem to be helping Nvidia more.

The mish-mash Enterprise, Embedded, and Semi-Custom division, which makes the game console CPUs as well as other custom gear and the Epyc processors, has its ups and downs, following the cycles of these various product lines which tend to have boom and bust cycles. In the first quarter, this part of the business had $532 million in sales, down 12.1 percent year on year but up 23.1 percent sequentially from the fourth quarter; it had an operating income of $14 million, which is a mere 2.6 percent of revenue.

Like other HPC and hyperscale businesses, you have to look at this business on an annual basis rather than on a quarterly basis. The third quarter of 2017, when the Epyc chips were first shipping, seemed to be a pretty good one for AMD’s Enterprise, Embedded, and Semi-Custom division. Revenues hit $824 million and operating income hit $47 million; this was lower than in the third quarter of 2016 for both revenue and profits, mind you, but we think that Epyc server chips were helping in the third quarter of 2017 more than many people think. And we also think servers are helping in the quarter just ended. In the trailing twelve months, the Enterprise, Embedded, and Semi-Custom division had $2.53 billion in sales, down 7.4 percent, and operating income was $90 million, down 72 percent compared to the prior twelve month period. Clearly there is some revenue and pricing pressure here, but we think this is mostly due to the console business, not the server business.

“Server revenue increased in double digit percentage sequentially, across mega datacenter, OEM, and channel customers,” Su said on the call. “Epyc processor unit shipments nearly doubled from the previous quarter. We continued to grow our datacenter momentum with dozens of new design wins across key workloads, including HPC, storage, virtualization, and cloud applications.”

We have reported on many of these design wins, including those from Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Dell EMC, and Cray. There are more than 40 server designs based on Epyc, and Su added that AMD is on track to have middle single digit server market share across units by the end of 2018. That was the number we were projecting back in March 2017, when we said that Epyc would give AMD a second chance in servers, and we also said that this would just be share and profits taken directly from Intel. Part of the reason that we think Intel has charged a pretty hefty premium for beefier versions of the “Skylake” Xeon SP processors is that it knew market share losses were inevitable in 2018 and it needed to make up that lost revenue and profit somehow. So far, that gambit seems to have worked.

Across the whole company, AMD had $1.65 billion in sales and brought $81 million of that to the bottom line in the first quarter of the year. That might only be 5 percent of revenue dropping to the bottom line, but it sure beats losing money, and we think that AMD will grow profits as demand for Epyc expands. Looking ahead, AMD is forecasting 50 percent growth in the second quarter, to $1.73 billion. Later this year, the 7 nanometer “Rome” kicker to Naples in the Epyc line will also sample and will go into production in 2019, and Su says that adoption of Epyc chips in the datacenter could accelerate.

“including the “K12” Arm-based chip that has yet to see the light of day and that probably won’t unless someone pays AMD to build machines with it”

Well that’s what semi-custom is for and AMD’s semi-custom folks should be jobbing that K12 IP around to some clients in addition to making sure that any custom ARM ISA Running IP can be paired with Vega Graphics and maybe some Mobile Gaming console sorts of semi-custom business. Maybe even a client that wants a semi-custom K12/ARM based server for some specific tasks that do not require x86 cores for some high density space constrained usage where x86 would be too thermally constrained.

I would have liked for AMD to have at least discussed K12’s core design at Hot Chips or some other technical event and maybe AMD should do so in order to attract potential semi-custom clients. Funds where expended designing K12 and if the blueprints are there then some of that expense could be offset via any semi-custom sales/licensing.

AMD is starting to remain in the positive category with respect to earnings per share and doing so at the low low gross margin rate of around 36%, but AMD does need to grow its gross margins a little more. And a higher percentage of high markup Epyc server sales paired with those higher markup Radeon Pro WX and Radeon Instinct compute/AI SKUs will be reflected in higher average gross margins than sales of any of AMD’s consumer based SKUs could produce, what with consumer markups/margins being so low in relation to the professional server and compute/AI market SKUs.

Intel, if it had to lower its margins into the middle 50% range, would have to resort to fat trimming due to Intel’s higher overheads in owning its own chip fabs and that upkeep that cost billions along with the 10nm process node R&D and development costs. And Intel has had to push its 10nm production more into the 2019 time frame as Intel appears to be having more issues with its 10nm than it had with its 14nm when Intel was first moving to that node.

AMD’s Zen/Zeppelin Die/Wafer yields are running above the 80% level so that scalable/modular Zen/Zeppelin die that AMD has made use of from its consumer Ryzen to its consumer Threadripper HEDT SKUs all the way up to its Epyc/server lines is really allowing AMD some pricing latitude with which to get back to its high Opteron levels of server market share and maybe higher. AMD’s Epyc CPU/SP3 Motherboard platform performance and MB feature sets are much more performant with the better memory channel options(8 channels per socket) and 128 PCIe lanes offered on both the 1P and 2P Epyc/SP3 MBs/Chipsets that AMD’s MB/Partners can offer up for AMD’s clients in the workstation/server market. So Epyc is much closer to Intel’s Xeon than Opteron could ever hope to be. And those Epyc SKUs priced closer to what AMD charged in relation to its Opteron SKUs will see Epyc’s price/performance metrics surpass Opteron’s price/performance metrics by a wide margin, and that’s getting plenty of attention now that Epyc is finally fully certified/vetted by those clients for production server workloads.

So for AMD that Epyc price/performance metric will see AMD really able to adjust its markups in a manner that Intel can not fully match without Intel having to give up its much needed higher margins. With the current high levels of overhead that Intel is carrying, those overhead cost will simply not allow Intel drastically cut markups/margins to compete without massive corporate restructuring and painful fat trimming. Even Intel in its latest quarterly guidance has mentioned increased competition pressures will make its 2H 2018 projections somewhat uncertain.

Intel has to compete more against Epyc’s Price/Performance metrics in the server market than directly against the Zen micro-architecture that used in all Epyc SKUs, as Intel still retains a smaller IPC lead against Zen. AMD has really created a great Epyc/MB ecosystem in which to become a factor again in the server market there is no question about that now. Intel also has to stave off IBM/Nvidia via OpenPower and Power9/Nvidia Volta in the HPC market coming down from the top and AMD’s Epyc coming up from the lower margin but better prices/performance metrics bottom.

So the next several business quarters are really going to be the most interesting to watch in decades for the server/HPC markets from a client perspective and an investor perspective.