IBM may not be the biggest provider of systems in terms of the size of its customer base, but of the top 5,000 or so companies worldwide that are not hyperscalers and cloud builders in their own right, Big Blue does have a sizeable share of the system budget. And that is probably not going to change any time soon.

Perhaps more importantly, with the integration of Red Hat and the commercial success of its OpenShift Kubernetes container platform and IBM’s own substantial software portfolio ported to run inside of containers, IBM’s overall slice of the IT budget at those top 5,000 accounts is probably going to expand while at the same time helping it bring tens of thousands of other reasonably customers into the IBM fold. The Red Hat base may not convert over to System z mainframes or even Power Systems iron any time soon, but some customers will and the rest will be upsold and cross sold all kinds of IBM software as they build out their hybrid cloud architecture.

That is the big idea that IBM had when it agreed to spend $34 billion almost three years ago to acquire Red Hat, and while we may lament the loss of Jim Whitehurst, former chief executive officer of Red Hat, as the future leader of IBM, we do believe that IBM is playing a long game and is sticking to the plan to be the companies that its existing large enterprise customers turn to when they implement a mix of private and cloud infrastructure to run their applications. And like IBM, and unlike Amazon Web Services, we have always believed that such hybrid infrastructure was always going to be the way modern IT gear and services for it were going to be consumed. AWS might have come around to this hybrid idea – witness AWS Outposts – but it has taken the success of legacy platform providers such as IBM, Microsoft, and Oracle to bring AWS around to this idea that not everything will end up in the public cloud and stay there forever and ever.

This is certainly the strategy that Arvind Krishna, IBM’s chief executive officer and chairman, was handed by his predecessor, Ginni Rometty, last year when she retired, and aside from spinning off approximately a third of itself into the Kyndryl managed services business, Krishna is sticking to the script.

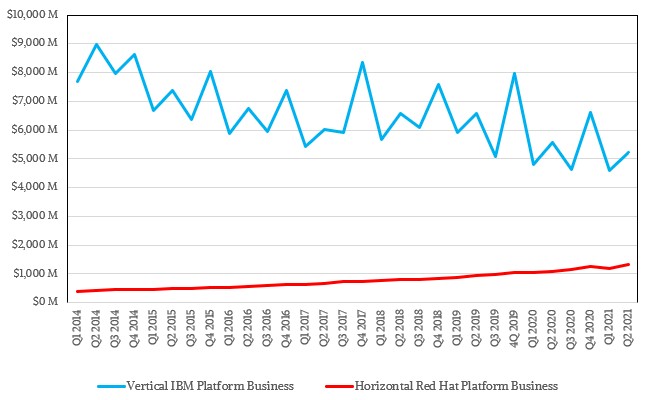

Krishna wants to rid IBM of its legacy outsourcing business – the one that saved its cookies in the 1990s and 2000s – and focus on the faster-growing and more-profitable systems business that it has with its own System z and Power Systems iron and their vertical stacks of software as well as the relatively horizontal stack of Red Hat systems software – really the Linux operating system and some JBoss middleware and OpenShift Kubernetes controller and a smattering of development tools and storage. The bet that IBM made three years ago was that the horizontal Red Hat business would grow fast enough to fill in the revenue declines in the proprietary IBM systems businesses. Like this:

IBM did not own Red Hat way back in early 2014, when we created this dataset that tries to extract the revenues and operating profits of Big Blue’s “real” underlying systems business from its quarterly financial results. Once Kyndryl is spun out by the end of the year, we suspect that IBM will rejigger its financial presentation and hopefully we can get a better read on this underlying systems business and its cloud business. Anyway, just because IBM didn’t own Red Hat until two years ago does not mean we should not show the historical financials for Red Hat to give a better sense of the data to try to project them forward. As we have pointed out in the past, if current conditions persist – that core System z and Power platforms business (not including the databases and application software that IBM sells) decline a few points a year and Red Hat grows at something between 15 percent and 20 percent per year, then by the end of 2025 or so IBM will get its $34 billion back in Red Hat revenues on its books and by the end of 2027 or so the Red Hat business should be bigger than that “real” IBM systems business.

That didn’t happen in the second quarter of 2021, of course. But IBM has taken another step in that direction.

In the quarter ended in June, Red Hat’s revenues grew 20 percent to $1.31 billion, normalized for IBM’s quarterly results, and about 3 percent of that growth came from currency effects converting overseas sales into US dollars. The currency effects on IBM’s overall business were a little more significant, according to its presentation, rising 4 percent and driving the company’s growth and then some.

Reported numbers are what matters, and if you are doing a lot of business overseas and bringing that dough back home, so be it. In the second quarter, IBM’s overall revenues rose by 3.4 percent to $18.75 billion, now the third straight quarter of consecutive growth for Big Blue. Gross profits rose in synch to just over $9 billion, but pre-tax income was down 1.2 percent to $1.55 billion and net income fell 2.7 percent to $1.33 billion.

With the System z15 and Power9 servers at the end of their cycles – new high-end Power10 machines are expected before the end of the year, probably in the late fall – it is no surprise that sales of both families of machines as well as related operating system and storage sales declined. These are still very much transactional businesses, where companies buy complete systems every three, four, or five years. The saving grace for IBM is that its mainframe software is rented on a monthly basis and therefore has cloud-like, annuity-style pricing. In fact, it would be hard to find a business more regular – or profitable – than mainframe systems software. It is the core of IBM’s real systems business and what profitability it has been able to retain over the decades.

At constant currency, IBM says that the System z business was down 13 percent, but that was against a tough compare when companies last spring activated a lot of mainframe capacity to deal with the enormous processing requirement increases they had due to the coronavirus pandemic. On the call with Wall Street analysts going over the numbers, Jim Kavanaugh, IBM’s chief financial officer, said that the z15 line has outsold the z14 line over the first eight quarters of their respective sales, and we suspect that this trend will continue until the z16 line is launched, perhaps late this year, perhaps early next year.

Here at The Next Platform, we only car about the mainframe because it gives IBM the money to do other interesting things, like continue to invest in Power processors and systems or quantum computing or advanced storage, and perhaps rejuvenate its high performance computing business. We certainly hope that can happen in the Power10 generation, and we shall see. IBM’s HPC business does not depend on landing big contracts for exascale systems at the national labs, which is both a good and a bad thing. This probably makes the HPC business that IBM can garner more profitable, but it is less bleeding edge than it might otherwise be and it doesn’t get a lot of airplay compared to what Nvidia, AMD, and even Intel to a certain extent get in the HPC and AI arenas.

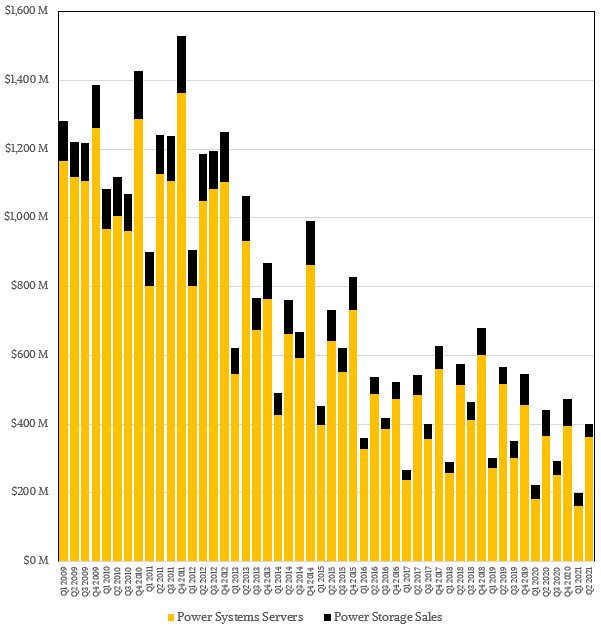

The Power Systems line, by the way, only had a 5 percent decline in the second quarter, which was a big improvement over the 13 percent decline it had in the first quarter. (Those are constant currency figures, again.) As part of our model, we try to estimate Power Systems sales every quarter based on the slim data Big Blue provides, and if you assume similar currency effects as IBM saw overall, then the Power Systems line had about $363 million in sales, and probably another $40 million or so on top of that for Power-based storage array hardware that should be attributed to the Power line. Call it a cool $400 million or so. There was probably also some Power system sales to the outsourcing part of Global Technology Services that will be spun out into Kyndryl, but it is very hard to quantify that. And if you want to really be fair about measuring the health of the Power Systems business, you would need to add in the Power-based server sales at IBM’s partner in China, Inspur. We have no idea how big or small that might be.

Anyway, here is what IBM’s external Power Systems sales looks like over time according to our model:

It is important to remember what is a model and what IBM said. What is very clear is that IBM needs for a Power10 rebound, and we will be watching to see how it packages up the Power10 processor into future systems and how they are received by customers.

That brings us to IBM’s “real” systems business, which is plotted on the blue line in the first chart in this story. If you add up the servers, storage, operating systems, transaction processing software, integration software, and financing of gear for the quarter, we reckon that brought IBM $6.54 billion in sales, down 1.7 percent, and with operating profits of $2.32 billion, down 12.3 percent. This is still a very big part of IBM’s business, and it sells a lot of other software and services on top of it to boot.

There is a global shortage of the COBOL programmers needed to maintain valuable (legacy) transaction processing codes in use worldwide. In my opinion, the reason for this shortage is lack of mainframes in computer science departments as well as lack of entry-level IBM systems affordable for individual developers. Combined, these two problems have essentially cut off the supply-chain of new developers for IBM Z and Power.

Could pricing deals and donations that get mainframes back in the universities and technical schools remedy the shortage of developers who are comfortable with the z/OS software environment? Not only could this solve the current shortages of talent needed to maintain legacy software, but it might increase market share as those new developers inform the decision makers about hardware for new projects. While at it, how about an affordable Power10 system as well?

keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

It is unfortunate that IBM did not do more to keep power chips in use in the high end embedded chip market in the early 2000’s. Power / PPC chips that were powerful, but under 20 watts, did well in embedded products until the early 2000’s. Then when Apple stopped using power / PPC chips in it’s MAC computers, IBM killed off a 15 watt power chip used in Apple

laptops. It didn’t help either that Apple bought up a power chip startup and had it’s employees work on ARM based products. After that, if one wanted a low wattage embedded processor with powerful cores, one usually moved to MIPs, x86 or ARM. Later on the move was less to MIPs and more to x86 or ARM.

Does IBM need to hold on to Power in addition to mainframe? I see a simplistic differentiation as intel at the low end, Power in the middle and mainframe at the top. Would getting rid of Power as an on premise option (or perhaps leaving that business for its partner in China) and using it more as a cloud only option with Power VMs help IBM consolidate and focus more on high end workload, or do you think there is a definitive middle of the ground Market with high growth potential that IBM is looking to stay in with Power?