Hewlett Packard Enterprise has reached the top of the HPC sector in an unconventional way, but one that could prove truly transformative for its new acquisition, legendary supercomputer maker Cray.

In a somewhat surprising development, HPE is shelling out $1.3 billion, net of Cray’s existing cash pile, to buy the supercomputer company just as Cray is on track to build three of the biggest systems the world has ever seen – all at the same time – and as its next generation “Shasta” systems and their integrated “Slingshot” interconnect gave Cray much broader applicability in the market than it has ever enjoyed.

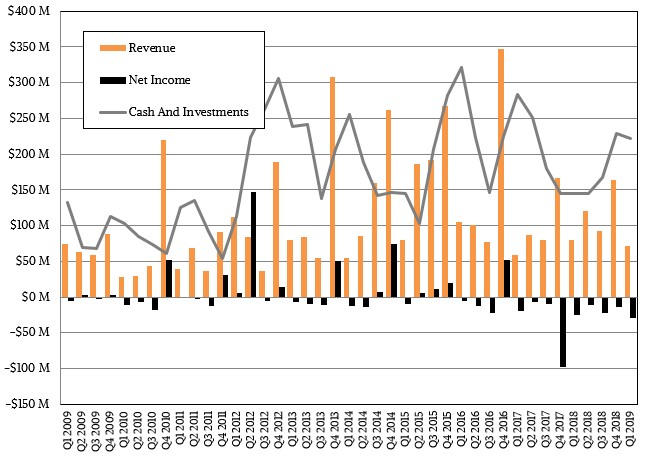

To one way of thinking, there has never been a better time to buy Cray, but conversely this is not a time that Cray was in any need of being acquired. Those pre-exascale and exascale systems at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Perlmutter), Argonne National Laboratory (Aurora A21), and Oak Ridge National Laboratory (Frontier) represent an aggregate of $746 million in system revenue alone for Cray, which is a big number for a company that at its largest brought in $724.7 million in revenues back in 2015. That was before a supercomputing slump started in 2016 and that got significantly worse in 2017, when Cray’s revenues fell by 45.8 percent to $392.5 million and it went into the red. Back then, the massive investments in exascale systems by national governments was not yet underway, but Cray was clearly pinning its hopes on the Shasta systems and Slingshot interconnect, deep partnerships with compute engine suppliers Intel, AMD, and Nvidia, and big investments to get it back on track financially again.

With those three big wins at US national labs, the payoff was visible on the horizon. There were plenty of risks, to be sure. You never count any chip, even your own interconnect, finished until it is. But Cray has demonstrated its ability to deliver technology over the past four decades, and it has mitigated some risk in the Shasta systems by employing many different kinds of interconnects and compute engines.

So it would seem at first blush that Cray did not need HPE. But there are a number of things that HPE brings to the table that mitigate the risks that Cray was still facing – and to be fair, has always faced, and with our great admiration, has always faced down, eventually.

As we have pointed out before, we have never thought that any of the chip suppliers should be prime contractor on any supercomputer deal unless they are actually building the systems. But the cost of the components in these pre-exascale and exascale systems is so large and the qualification and acceptance process for these machines is so rigorous and time consuming that it was hard for either SGI or Cray to lock up the capital to do these big deals and still have funds left over to expand the business in other areas.

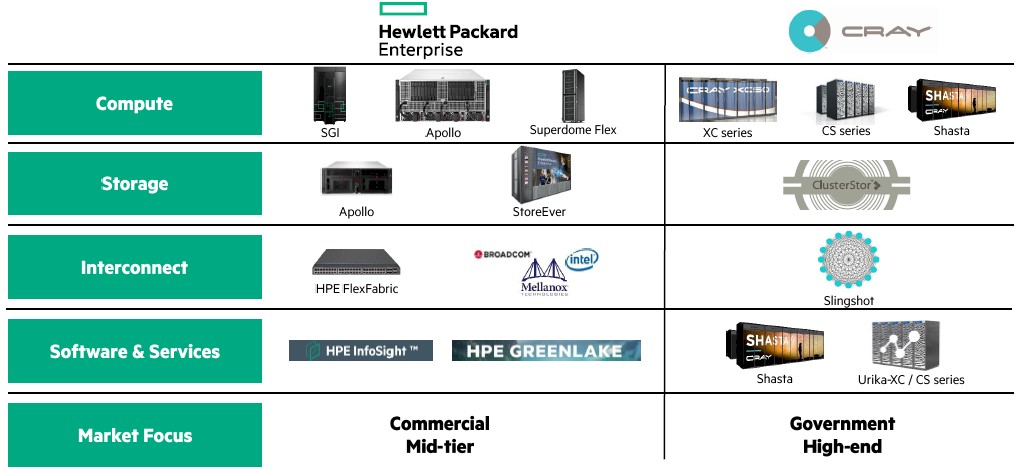

HPE is roughly 50X as large as Cray, so it has the financial heft to take down these big deals without breaking too much of a sweat. And equally importantly, thanks to its vast ProLiant server business, HPE has financial leverage with processor, memory, flash and disk storage, and networking suppliers, which in theory should help make the Cray business more competitive and more profitable over the long haul. That was the idea behind HPE’s acquisition of supercomputer maker back in August 2016 for $275 million (net of SGI’s cash). SGI is integral to HPE’s battle against IBM for the large NUMA systems that support SAP HANA workloads, and gave HPE some other traditional HPC assets to sell as well.

HPE is buying Cray to keep Dell, IBM, and Lenovo in check in the HPC space, and also to prevent Cray from falling into enemy hands. IBM used to dominate in the HPC space, but when Big Blue sold off its System x business to Lenovo in 2014, it basically sold off the lion’s share of its HPC business. And when Dell bought EMC, the HPC portions of that storage business (driven by Isilon arrays) plus organic growth as Dell got more aggressive in the HPC arena, vaulted Dell to the number two position behind HPE. (These rankings are based on analysis by Hyperion Research.)

In its fiscal 2018 ended in October, HPE generated $2.1 billion in HPC sales, up 25 percent year on year. By the numbers, Cray grew by 16.2 percent in calendar 2018 to $455.9 million, and booked $72 million in losses. But the core supercomputing business, as we have said many times before, has lots of ups and downs, as the chart for Cray below demonstrates:

About 80 percent of Cray’s sales in the past year came from systems sold into government labs around the world, and only 20 percent came from customers in the commercial sector. This is a big improvement for Cray over the past few years, and represents many smaller deals. But HPE is the king of the small HPC deal and knows how to make it up in volume, thanks in large part to its global reach, just at the same time that Cray has engineered the Shasta systems, which start shipping at the end of this year and which ramp through 2020 and beyond, to fit into standard 19-inch, air-cooled racks as well as its own custom liquid cooled racks.

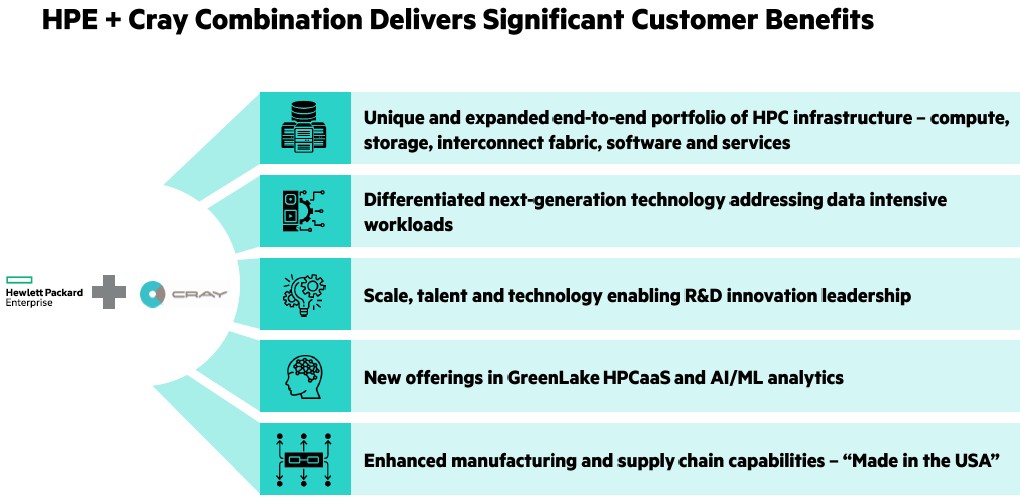

Both HPE and Cray have been chasing the same markets, with HPE shooting higher and trying to take down exascale deals and Cray trying to shoot lower to try to broaden out its base while at the same time preserving and expanding its business in the supercomputer realm. The exascale opportunity is on the order of $4 billion in revenues worldwide in the next five years, according to Intersect360 Research, and the overall HPC market was worth about $28 billion in 2018 and is growing at 9 percent at a compounded annual growth rate, according to Hyperion. Buying Cray is one way that HPE can secure more share of both of these slices of the HPC market, and perhaps hit 40 percent share of the HPC system business and expand upwards from there.

It is absolutely unclear how HPE will rectify the overlaps between the SGI and Cray lines, but it seems likely that both will survive given their different architectures. The big SGI NUMA boxes will be used for shared memory workloads, the ProLiants will be used for cheap as chips clusters that are loosely coupled, and the Shasta/Slingshot systems will be used where more sophisticated coupling at a scale where NUMA can’t go is needed.

HPE really wanted to win an exascale deal, and the fact that it has bought Cray is probably an indication that this is not going to happen. And it looks like Cray might be having a higher success rate on exascale systems than many might have predicted. So the combination of the two will fulfill the needs of both companies. Cray gets to be part of a much larger company, and HPE gets to be a big HPC player, not just the one making the most money from the belly of the market. And HPE is also less reliant on Mellanox Technologies (soon to be a part of GPU chip maker Nvidia) and Intel (which wants HPE to push its Omni-Path interconnect) for networking gear in the HPC space, thanks to Cray’s Slingshot.

As far as we know, the 1,300 employees of Cray will be joining HPE, and the Cray business will be absorbed into the HPC business unit at HPE. We suspect that the Cray brand may live on in high-end machines, but perhaps not – and if that happens, that will be a shame. Cray means, and has always meant, supercomputing.

The Cray acquisition for $35 per share, which works out to around $1.3 billion net of the cash that Cray has on hand, has been approved by the board of both companies, but the deal, which should close by the end of the calendar year or maybe early 2020, is still subject to the approval of Cray shareholders. Before the deal was announced, Cray had a market capitalization of just over $1 billion and had $228 million in cash, so the HPE deal represents a 62 percent premium over Cray’s market value if you net out the cash on both ends. This is a pretty healthy profit for Cray shareholders, particularly those who bought in 2016 and 2017 when the stock was trading at half of the level that HPE is paying. Still, given that this is Cray we are talking about, it just seems like it should be worth more than that.

I hope that this deal will not put AMD’s x86 based HPC/server offerings at a disadvantage over the longer run. So after this HP acquisition of Cray recieves it’s proper US Justice Dapartment review, the x86 market needs to be monitored even after approvial.

The entire PC/Laptop and HPC/Server systems market is dominated by the x86 ISA/ISA ecosystem to such a degree currently so any one x86 CPU maker’s market history with regards to market tactics and OEMs(big and small) needs to be kept in mind and continously monitored.

Also I do not see why HP/Others can not make use of some OpenPower offerings also as that’s even better for some non x86 based HPC options as well. ARM designs also but HP is already offering “Moonshot”/others options.

Maybe Cray can now get some cash infusion and continue to be in competition in that federal systems market as well as server/cloud systems market. AI is really starting to grow at a more rapid pace compared to the Traditional server market’s growth rate.

There are rumors that the Zen3 based Epyc/Milan will support SMT4 and that probably means that things are going to get even wider order superscalar from AMD on its Zen3 based server designs, if that is in fact the case about Epyc/Milan and SMT4. IBM’s power8/power9(SMT4 and SMT8 variants) for example has that SMT8 and really the widest order superscalar instruction issue rates and total numbers of execution ports as well. AMD must really be having to consider some L4 cache on its I/O die for Epyc/Milan also in order to support SMT4 if true.

So OpenPower’s/IBM’s centaur I/O dies each have 16 MiB of eDRAM to avoid having to suffer for the incresaed latency that comes with having to access System DRAM. The more levels of cache on a system the more chances to hide latency issues by having the code/data already residing on some cache level as opposed to being out on system DRAM and requiring the most added latency to get at.

The Exascale ERA is almost here!

It’s ironic that HP has to fight its way back into the HPC market after is dominated the Top500 list in 2002, 2003, 2007 and 2008. In the November 2003 list they held both place 2 (ASCI Q) and 5, while in the November 2008 list Cray already dominated the Top10 (5 out of 10) and HPE didn’t have a single Top 10 machine anymore.

Doesn’t seem like a terribly good stock price premium, given all the good news Cray has been having lately.

I believe the premium would have been higher had the stock price had some more time to reflect current government wins. I won’t be voting my shares for this sale at this time.

I suspect that the Cray brand may live on in high-end machines, but perhaps not – and if that happens, that will be a pity. Cray means, and has always meant, supercomputing.

I think this article is shilling a bit much for the deal. I don’t think these statements are entirely true:

“Hewlett Packard Enterprise has reached the top of the HPC sector”

“there has never been a better time to buy Cray”

“With those three big wins at US national labs, the payoff was visible on the horizon”

“Both HPE and Cray have been chasing the same markets”