You would have to look far and wide to find a tougher business to be in than chip manufacturing. Which is why the many dozens of server makers who used to make their own CPUs – often multiple types – no longer run their own foundries or, with the exception of IBM and now Amazon Web Services, no longer exist. In fact, AWS is the first new vertically integrated server designer we have seen enter the market in a long, long time – and even Jeff Bezos is not crazy enough to launch his own chip foundry.

It may yet come to that, and someday a company like Globalfoundries might even have financials and a balance sheet that would warrant a big investment from a neo-oligarch like Bezos, or even an outright acquisition. But if the form F-1 filing by Globalfoundries this week announcing its intent to go public on the NASDAQ stock market in New York is any indication, that day is going to be a long time off. At least until the chip maker – which is an amalgam of the old AMD and IBM foundry businesses with some Chartered Semiconductor tossed in for spice and then a whole lot of IBM bones removed – shows more profits.

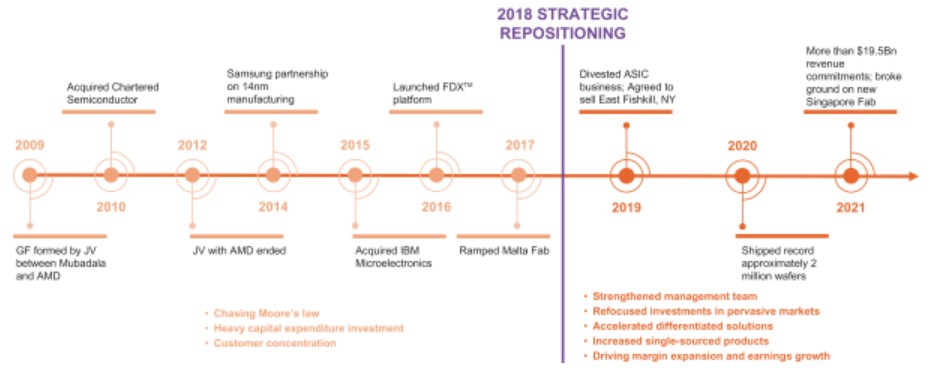

Being privately held since its founding, with AMD and the government of Abu Dhabi as its two sole shareholders, we never got a look inside the company. And the F-1 filing only shows financials for the past three years, so it is by no means a complete dataset. Globalfoundries was spun out of AMD, and the government of Abu Dhabi spent some $23 billion buying up Chartered and IBM Microelectronics and investing in fab capacity as it pushed from 28-nanometer processes down to as low as 12 nanometers and then hit the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography barrier at 7 nanometers and decided to stop.

Well, technically, IBM paid Globalfoundries to take its foundry business in 2015, and is now suing for breach of contract, trying to get $2.5 billion in compensation and damages. Part of the reason behind that suit is that Globalfoundries, in August 2018, spiked its 7-nanometer chip-etching efforts. Rather abruptly. That left both IBM and AMD to go searching for other CPU chip partners. AMD went to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. for its cores, but kept Globalfoundries making the memory and I/O chiplet for its “Rome” and “Milan” EPYC CPUs. IBM went to Samsung for its “Cirrus” Power10 chip, which first came out a few weeks ago in the “Denali” Power E1080 big iron machine and which will ramp into smaller boxes in the first half of 2022.

At the time, there were the two only options for 7-nanometer chip manufacturing. Intel was plagued by delays in its 10-nanometer processes and then at 7 nanometers as well, and the difficulty of making money on its relatively low chip volumes – Big Blue only sells tens of thousands of its own Power and z chips every year – coupled with the loss of the game console compute and graphics businesses to AMD a few years back – pretty much sealed the fate of IBM Microelectronics. IBM did not have the cash or customer base to be a captive or merchant foundry, or a mix of the two.

Looking at Globalfoundries numbers, it is arguable that it will ever make a buck here, too – even with rampant chip shortages and even with TSMC leaving its rear unguarded on vintage foundry processes. And seeing the financials that it has posted makes it seem a whole lot less likely that Intel will try to buy Globalfoundries, which was a rumor going around a few months ago.

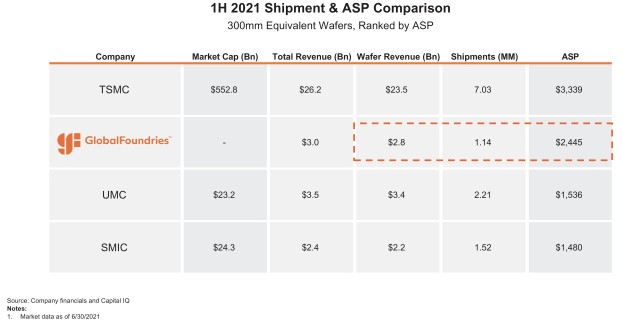

And frankly, we have no idea if Intel Foundry Services will make any money when and if Intel ever breaks out its foundry financials separate from its finished chip financials. We don’t know how much of a drag the foundry business is on Samsung, either, but someone has to make the memory and flash in the world. TSMC seems to be making money as a pure-play foundry, which we talked about in August, with revenues up 28 percent in the second quarter ended in June to $13.32 billion and net income of $4.81 billion, or 36.1 percent of revenue. That is software-class profiting, and then some, with a hard-core, capitally intense hardware business. Amazing, really. This is what having a monopoly on advanced processes can do for a chip maker. But it has taken a lot of investments in research, development, and capital equipment to get there, and that is why TSMC has almost $32 billion in cash in the bank right now, which unfortunately is about enough to build one and a half advanced chip fabrication facilities, or fabs.

Even when you are rich at this foundry game, you feel poor. And that is because, as Globalfoundries points out in its F-1 filing, a modern foundry supporting five-nanometer-class chip making using EUV technologies is going to cost around $20 billion. You have to push a lot of wafers through this fab to get your money back, and success in one process gives the cash to be successful (each foundry hopes) in the next process. Every fab is a big bet on what volumes might be five years into the future, and every generational process improvement is a bet on an uncertain future, as Intel and Globalfoundries have demonstrated. Intel had its 10-nanometer and 7-nanometer woes, and Globalfoundries had issues with 22-nanometer processes and then 14-nanometer processes (according to Big Blue), and then spiked both its 10-nanometer and then its 7-nanometer efforts when they proved too costly for the volumes anticipated.

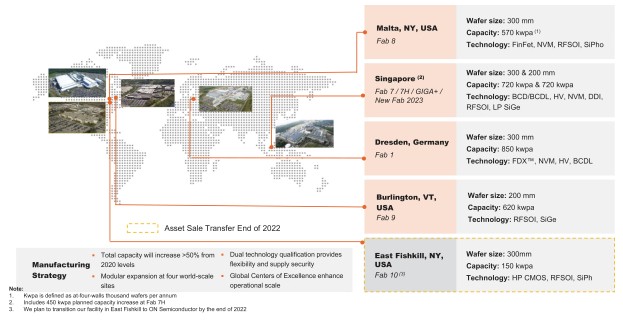

Globalfoundries has very good reasons to play it conservatively. It cannot afford to play the game any other way. That’s why its recent investments have been modest: $1 billion to expand its Fab 8 facility in Malta, New York, adding 150,000 wafers per year of capacity and another $1 billion for the Fab 1 facility in Dresden, Germany. That expansion in Fab 8 is to balance the capacity it is going to lose when it sells of the Fab 10 facility in East Fishkill, New York, which used to be the main facility for IBM Microelectronics and which Globalfoundries is selling off to ON Semiconductor for $430 million; that deal was announced in 2019 and should be completely paid completely off by the end of 2022.

Globalfoundries operates three foundries in Singapore – Fab 7, Fab7H, and GIGA+ – and has a new fab slated to come online in that island nation in 2023 based on 300 mm wafers. There is also a plan to add an additional fab in New York. All of this fab building will be funded through “public-private partnerships,” which means the state and federal governments are going to kick in. And given the initial public offering, it looks like the government of Abu Dhabi is looking to cash in on the semiconductor shortage and cash out of some of its Globalfoundries stock rather than pump tens of billions of dollars into the company and hope to cash out bigger later. The amount of shares and the striking price for the IPO have not been set yet, but tongues have been wagging since the summer that the chip maker was seeking a valuation of around $25 billion, and the IPO will be a slice of that value.

If Globalfoundries were making more money, it would surely be easier to get a higher valuation. But the truth, we learn from the F-1 filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, is that the company is hemorraging money. Like many startups from the same era of the late 2000s still are – we are thinking of Nutanix and Pure Storage in the enterprise storage space as two prominent examples.

In 2018, which is when Globalfoundries was shipping 14-nanometer Power9 and 22-nanometer System z14 mainframe processors to IBM as well as 14-nanometer “Naples” EPYC 7001 CPUs and “Vega” and “Navi” Radeon GPUs to AMD, revenues were just a tad under $6.2 billion. Bbut because of high costs of running the fabs and very high R&D costs (nearly $926.2 million), losses came in at $2.77 billion.

This was the same year that chief executive Tom Caufield did a “strategic repositioning” of Globalfoundries, and it subsequently sold off its custom ASIC business (which was a big chunk of the IBM Microelectronics team) to Marvell for $650 million (with a potential $90 million kicker), and sold off its Fab 3E facility in Singapore to Vanguard Semiconductor for an undisclosed amount. This is when the 7-nanometer process was spiked and Globalfoundries said it wanted to rule the 12-nanometer and larger process world that Intel, TSMC, and Samsung were not serving as well as they might if they were not too busy trying to do advanced processes all the time. In 2019, when the ON Semiconductor deal was done to sell off the East Fishkill Fab 10 facility, revenues fell by 6.2 percent to $5.81 billion and gross losses increased a bit, but net losses shrank to $1.37 billion due to the restructurings and cutting R&D by 37.1 percent. In 2020, when the IBM Power9 and System z15 processors were winding down (the latter being a 14-nanometer mainframe chip companion to the Power9) and AMD Naples sales were done, revenues dropped another 16.6 percent to $4.85 billion, and gross losses rose by a third but because of further belt tightening outside the fabs, net losses were down a tiny bit to $1.35 billion.

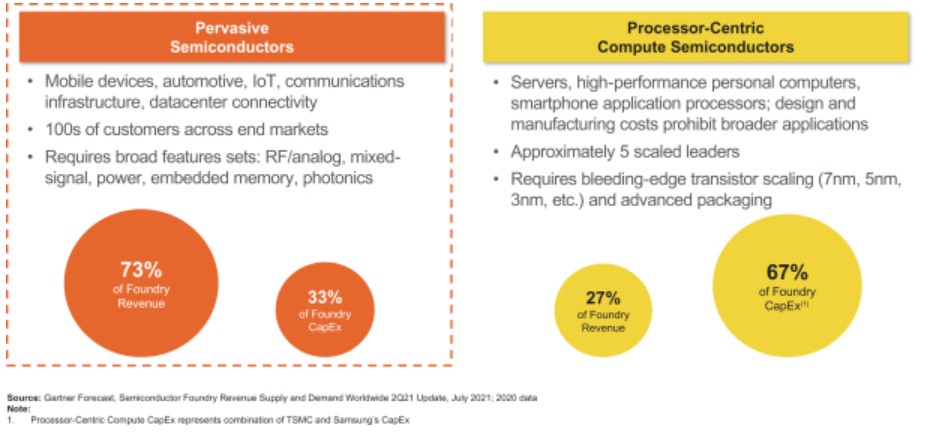

Any way you cut this, Globalfoundries needs to boost revenues back to 2018 levels and not do anywhere as much investing to just tread water at 12-nanometer and larger geometries. So the question becomes: Is there enough revenue in process sizes ranging from 350 nanometers to 12 nanometers to maybe rake in $7 billion in sales and actually create a profitable company here? And our second question is: Can Globalfoundries get profitable enough, and get enough support, to become a leading-edge foundry again, and therefore make it more interesting in the datacenter?

In the past two years, Globalfoundries has been able to get a handful of customers who are committed to its fabs for various kinds of devices – a single-source agreement, which seems dangerous in these days – and in regular volumes, and they make use of a bunch of different processes in various transistor geometries and chemistries, including fully depleted silicon-on insulator (developed by IBM for Power chips so long ago) and FinFET CMOS as well as silicon germanium and various silicon photonics chippery. As the IPO prospective is coming out, Globalfoundries had revenue commitments for such deals of $19.5 billion, with $10 billion of that running from 2022 through 2023 alone and $2.5 billion in advanced payments that lock in production time and space in the fab.

Single-sourced business comprised 61 percent of wafer shipment volumes in 2020, up from 41 percent in 2018 – which means customers are trusting Globalfoundries for vintage and mature processes that are perfectly fine for the chips they are making. In the first six months of 2021, the top ten customers at Globalfoundries were: Qualcomm MediaTek, NXP Semiconductors, Qorvo, Cirrus Logic, AMD, Skyworks, Murata, Samsung, and Broadcom. In 2018, single-source agreements represented 69 percent of design wins; in 2020, of the 350 design wins that Globalfoundries had, 80 percent were single-sourced.

One might quip that people didn’t learn from the experience of IBM and AMD. But they did. Globalfoundries does not struggle with mature processes – it is really good at that. And maybe, just maybe, it will pick up some 7-nanometer experience and used equipment while TSMC, Intel, and Samsung are chasing 5-nanometer, 3-nanometer, and heaven knows what else. (-2 nanometer, -5 nanometer, -7 nanometer?) It could happen. Stranger things have.

So where does Globalfoundries stand among foundries? Well, it needs money. That’s obvious, and for whatever reason, the government of Abu Dhabi is a whole lot less enthusiastic of about becoming a silicon powerhouse than it was in 2009. This is a hard business, and it takes ever-increasing financial, technical, and emotional commitment that few have the stomach for. (So does the HPC business and the server business, to name two others.) The company’s fabs kicked out around two million 300 mm wafer equivalents for more than 200 customers in 2020, and is growing that customer base and wafer volume as fast as it can. While the company has over 10,000 patents, thanks to the portfolio it got from AMD and IBM, it will need to move on to smaller processes at some point and that means either doing R&D or buying it. Expertise in chip packaging and design might come in handy, but it sold the latter off to Marvell. Sometimes, you have to burn the furniture to keep from freezing.

It will be interesting to see what Wall Street does with this and how much money Globalfoundries can raise.

Be the first to comment