The supercomputing business, the upper stratosphere of the much broader high performance computing segment of the IT industry, is without question one of the most exciting areas in data processing and visualization.

It is also one of the most frustrating sectors in which to try to make a profitable living. The customers are the most demanding, the applications are the most complex, the budget pressures are intense, the technical challenges are daunting, the governments behind major efforts can be capricious, and the competition is fierce.

This is the world where Cray, which literally invented the supercomputing field, and its competitors live. About the only thing more intense these days is the ODM environment where the hyperscalers design and build their massive infrastructure.

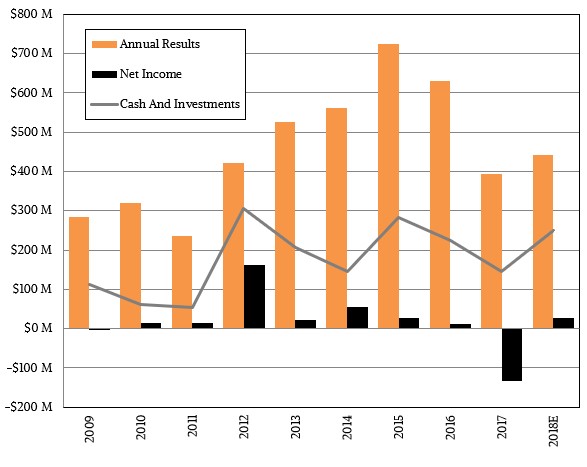

Despite the rosy proclamations about how healthy the HPC market is and an uptick in supercomputer spending in the first half of 2017, Cray has contended for quite some time that there is actually a slowdown in the supercomputing sector. Moreover, this slowdown hits Cray the hardest because it is the dominant player up where scalability and performance matters most. In a conference call with Wall Street analysts going over its financial results for the fourth quarter of 2017, Cray chief executive officer Pete Ungaro explained that the target markets in which Cray plays were down by more than 60 percent compared to the levels those markets were at back in the local maximum peak set in 2015. If you do the math on Cray’s financial results, comparing 2015 to 2017, the company’s revenues have dropped by 46 percent. When you contract by less than your target market does, that is called winning, even if it does not feel as good as the extraordinary growth that Cray rode up in 2015.

Cray has always contended that it was a company that had to be looked at on an annual basis, rather than quarterly, given the uncertainties in spending among HPC centers in government, academia, and companies. But even if you do this, there is no getting around the fact that the past few years have been disappointing, and 2017 especially so. As we have said before, Cray has aspirations to be a $1 billion company, and we think that, in the fullness of time, it can reach that goal and be a profitable company to boot. There is no shortage of need for the kind of expertise that Cray has. The issue is more of a budgetary one within the HPC realm, and Cray needs to also continue to push its wares into commercial institutions where money can be found for projects with good return on investment. It is a hard thing to argue for a premium product in any market, but that is precisely Cray’s task – as it has always been.

“We believe multiple factors contributed to this slowdown,” explained Ungaro in the call with Wall Street earlier this week, “including a challenging government funding environment in multiple countries around the world, a slowdown in the pace of technology improvements and processors, increasing memory cost, a slowdown in the energy market, and a general delay in decision making as large customers took a pause in replacing older systems.” Ungaro added that many HPC clusters out there were now beyond their normal four-year upgrade cycle, and said that given this, there was pent up demand in the HPC sector that, ultimately, will need to be fulfilled. The memory and flash price spike, which started ramping in late 2016 and that has resulted in main and flash memory being 2X to 3X more expensive, is a terrible drag on the server business. It has not helped that demand for Nvidia’s “Pascal” and “Volta” Tesla GPU accelerators has been higher than anticipated, and that Intel’s “Skylake” Xeon SP processors were not only much later than expected, but also have higher prices than many expected. None of this is greasing the skids for HPC, as the “Haswell” Xeons, 100 Gb/sec InfiniBand and Ethernet, and relatively cheap memory and flash were back in 2015.

The HPC business in general and the supercomputer business (meaning machines that cost $500,000 or more and that are aimed at accelerating a few applications rather than running many concurrent yet smaller applications) specifically have always had tumultuous revenue and profit cycles, and there is no reason to get overly dramatic about it now. And Ungaro is not about to, either.

“While this has certainly been a more pronounced sustained downturn than what we have seen in previous cycles, we do not see a fundamental shift in the industry,” Ungaro told Wall Street. “And we continue to believe that the market will rebound over time, beginning this year. The long term demand drivers are intact and the trends continue to favor the incorporation of more and more data into large scale simulations, deep learning algorithms, and big data analytics.”

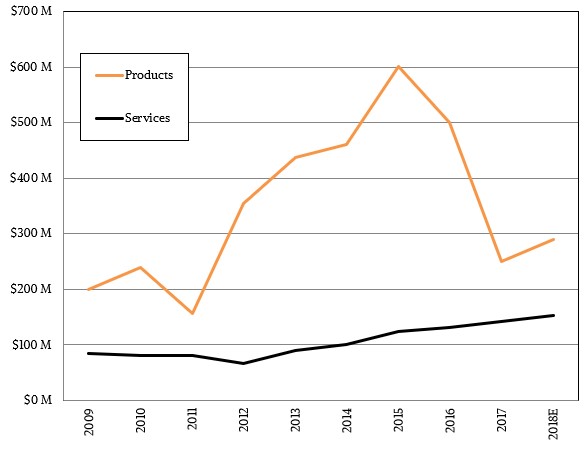

In the fourth quarter ended in December, Cray posted product sales of $132.3 million, down a gut-wrenching 57.5 percent compared to the year-ago period when Cray booked a record quarter in its history. Services revenues, which include consulting and design services as well as technical support and maintenance, kept chugging along and only fell by 2.2 percent year-on-year and were flat sequentially. Cray kept a tight lid on operating costs, but can’t do much about the cost of compute and storage, which without a doubt ate into its profitability as it is doing with all system vendors in the IT sector. (And the memory and flash makers are in no hurry to boost the capacity of their fabs and drop the price, either.) Cray had a minuscule operating loss for the fourth quarter, and then it went and booked a $102.2 million charge relating to taxes on its overseas profits, which is due to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 passed by the Trump administration and Congress late last year. All of the major IT players are taking these charges now, and some of them are quite large and have pushed them to report losses, too. But going forward, they will be able to repatriate their cash and they will also have a substantially lower nominal tax rate and, thanks to tax accountants, an even lower actual tax rate. This charge pushed Cray to report a $97.5 million net loss, but it sets the company up to be more profitable in the future – provided component prices don’t rise again, of course.

In the fourth quarter, overall revenues were down 13.1 percent to $166.6 million. Cray missed its most recent revised goal of hitting $400 million in sales for the year, and it missed that goal by $7.5 million because some relatively small deals were pushed out into this year. On an annual basis, Cray’s revenues were off 37.7 percent to $392.5 million, and it booked a $133.8 million net loss.

Cray has been pushing its sales team to make inroads into commercial companies and to not be so reliant on academic and government HPC centers for sales. This has been a slow process, but a successful one. Ungaro said that 12 percent of revenues for 2017 came from such commercial customers, about twice the level that it saw in 2016. If you do the math on that, this means Cray’s commercial accounts drove $37.8 million in sales in 2016, and despite the large revenue drop, Cray was able to grow its commercial HPC business by 24.6 percent to $47.1 million in 2017. Assuming it can grow at the same rate or maybe a little higher in 2018, then commercial accounts should bring in around $60 million in sales.

Cray is one of the few companies in the tech sector that provides guidance to Wall Street, and says that it expects for revenues to be around $50 million in the first quarter and for sales to grow between 10 percent and 15 percent for all of 2018. That would represent a 15.1 percent decline in sales for Q1 2018, and it would mean that Cray expects for annual sales to be on the order of $432 million to $451 million. At the midpoint of that revenue guidance for 2018, and assuming there is around $60 million in commercial HPC revenue, that means that the core government and academic HPC business would grow at around 10.8 percent and deliver $382.7 million in revenues. (We have taken a stab at predicting Cray’s 2018 numbers based on these assumptions.)

Cray surely could have used that “Aurora” pre-exascale system to go into Argonne National Laboratory this year as it was originally planned, but now a different machine being proposed by Intel is set for 2021. That is for sure. But with Intel as the prime contractor, it is not clear how much of the $200 million being invested in that now discontinued “Knights Hill” Xeon Phi and Omni-Path 200 cluster would have been brought to Cray’s top and bottom line anyway. Cray will be refreshing its product line, top to bottom, in the coming year, which should help. But this is less about hardware than it is about a commitment to a certain kind of computing to drive simulation, modeling, analytics, and machine learning applications.

There is hope in the future for a broader turnaround, according to Ungaro, who has seen his share of HPC ups and downs in his long career at IBM and then at the helm of Cray.

“Market activity at the high end is not yet as strong as we would like, but we are seeing early signs of a rebound beginning this year,” said Ungaro. “Customer plans are beginning to firm up as well as necessary funding. As such, 2018 is shaping up to be significantly more active, especially in bidding for new systems. It is currently looking like we will bid on more than three times as much business this year compared to 2017. Some of this is for revenue in 2018, but much of it would be for targeted for delivery and acceptance in coming years, including 2019 and beyond. As a result, in addition to driving revenue growth over 2017, we are cautiously optimistic in the prospects for significantly higher bookings over the next couple of years.”

It is ironic, of course, that the very people who are in the business of simulating, modeling, and predicting the future have such a tough time trying to assess the potential demand for exotic systems. That just goes to show you that turbulent systems like weather or combustion are a hell of a lot easier to model than what human beings will do with money to try to make more money. That, ultimately, is what supercomputing needs to be about. It cannot just be about doing good or satisfying curiosity. It has to be about doing well, too.

With Intel killing the Xeon Phi line, the runway is clear for Nvidia. However, Nvidia have become quite greedy (the recent prohibition on running graphics GPUs in DC) and I think will sow the seeds of their own downfall, till Intel or maybe even ARM catches up with its own exascale chippery. For now it will be Xeon + GPUs I think and then totally different architectures from the incumbents. Expect the top end supercomputing line to fragment

Physical limits (speed of light on path length and wavelength on circuit mask resolution) will force migration away from “generic” computing and make us look at specific solution machines again. We already see this specifically in FFT (GPU and Bitcoin miners for example). With the massive interests in Deep Learning and Massive Data mining, I believe the next big thing will be better support for Inference Engines in hardware acceleration.