Chip maker Intel has been getting a lot of grief in recent days about missing the boat on putting chips in Apple’s iPhone back when the product was announced back in 2007, and then subsequently also losing out on the opportunity to have Intel Inside the Apple iPad tablet that came out three years later. Say what you will, but the folks that have been running Intel’s Data Center Group have not missed any boats, but rather have built a warship.

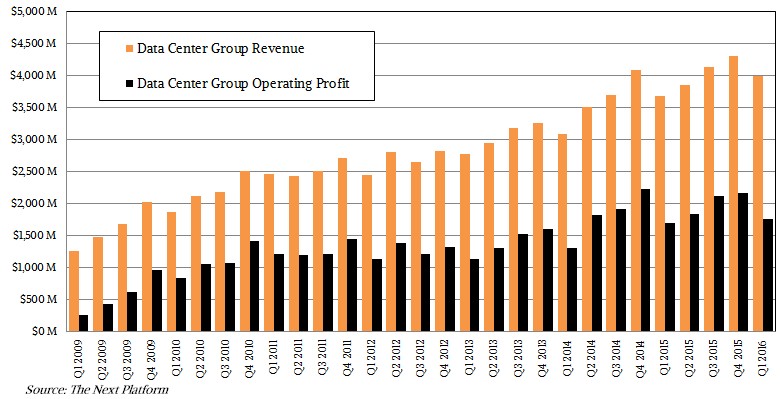

As the traditional PC client business continues to erode, the part of the company that is dedicated to the glass house is doing its part to keep Intel growing and profitable, even with some ups and downs due to issues with ramping up new manufacturing technologies and applying them to Xeon, Xeon Phi, and other processors used in the datacenter. This business has, despite all of the moving parts and their own ups and downs, been remarkably predictable. Take a look:

The first quarter sets the new water mark for each year and then the revenue tide rises again in almost a straight line, with the exception of the slight drought between the “Westmere” and “Sandy Bridge” Xeon chips in 2011. The growth in operating profits for Data Center Group is a little less predictable because the costs of bringing new process technologies to Xeon and related processors for servers, switches, and storage and, we think, because of the pricing pressure that hyperscalers put on Intel when they do very large server rollouts. The one thing that seems obvious is that Data Center Group probably accounts for one of the largest pools of hardware profits in the datacenter, and that is so by design and Intel has done brilliantly leveraging its paranoia about competition to drive others from the datacenter.

But the question that customers that buy Intel gear or that invest in the company’s stock want to know is will this gravy train last? Will ARM and Power chips start taking out bites? Or has Intel fortified the glass house against entry to such an extent that it had maintain what is essentially a monopoly and continue to extract vast profits from its compute engines? A lot depends on how it expands and where.

In the first quarter ended in March, Data Center Group posted sales of just under $4 billion, and brought $1.76 billion in operating profits to the middle line. That operating profit represented 44.1 percent of total revenues for Data Center Group, which is lower than in other quarters because Intel is incurring the costs of the 14 nanometer ramp for both the “Broadwell” Xeon D and Xeon E5 processors and because it is seeing an uptick in sales of lower-end Xeon processors and other chips aimed at the networking business. In the first quarter, unit chip volumes were up 13 percent, but overall average selling prices were down 3 percent – and that is with hyperscalers buying the new Xeon E5 processors during the entire quarter ahead of their formal March 31 launch, as Jason Waxman, general manager of the cloud computing group, told The Next Platform recently. They are buying chips that have dozens of Xeon cores and cost several thousands of dollars a pop, but even this is not enough to make up for the fact that in the networking segment, Intel saw a 60 percent growth in chips shipped, but these are selling for hundreds of dollars rather than thousands and that brings the ASPs down overall a bit.

Over time, it is hoped, when Intel gets more established in networking, as it has become in core compute and as the engines behind appliance-style storage arrays and generic storage servers, it will be able to compel network device makers to move up the stack and spend more money on more sophisticated chippery. This strategy has played out brilliantly in core compute, and we think Intel will also get an increasingly high attach rate for its server adapters and its Omni-Path interconnect, too.

While the IT sector has gone into a bit of shock about Intel laying off approximately 12,000 employees between now and the middle of 2017, which will cost it about $1.2 billion while also removing about $1.4 billion in ongoing operating expenses from its ledger, this is precisely the time for Intel to take such action. The PC business is not going to get any stronger and the company is inclined to focus on the high-end segments where, starting next year, AMD will be re-entering the field with much-improved “Zen” processors and associated GPUs. Some of the money that Intel is getting from the cuts will be reinvested in the Data Center Group and the adjacent Non-Volatile Storage Solutions Group, which in conjunction with partner Micron Technology makes flash cards and SSDs and is working on 3D XPoint memory that will be employed in SSDs starting this year and in DRAM-style memory sticks next year concurrent with the rollout of the “Skylake” Xeon E5 v5 processors, and its Internet of Things Group, which is peddling Intel compute and networking to companies seeking to embed these functions into all manner of products to feed telemetry back to their makers for data analytics. Intel thinks IoT-enabled stuff is the next big wave of devices that will help keep demand for servers, storage, and networking growing at least as fast as a Moore’s Law curve, and given the fact that Intel cannot easily pry its way into smartphones and tablets now (where ARM is the hegemon by a ridiculous margin, just as Intel is in the datacenter), this is about the only bet that Intel can make aside from driving up cloud adoption and currying favor with hyperscalers.

Keeping engaged with hyperscalers and cloud builders is the main reason why Intel spent $16.7 billion to acquire FPGA maker Altera, a deal which was rumored for years, announced last June, and completed as 2015 was winding down. For the moment, the Programmable Solutions Group that is made up of the Altera business is pretty small: a mere $359 million, and after adjusting for around $100 million of deferred revenue when Intel put Altera on the books, it grew in the middle single digits, and it had an operating loss of $200 million thanks to over $300 million in charges relating to the deferred revenue and inventory charges. Ignoring all of these charges, Intel CFO Stacy Smith said on a call with Wall Street analysts this week when going over the numbers that the FPGA unit had low double digit operating margins – pretty low compared to 50-ish percent level that Data Center Group tends to maintain over the long haul of a year.

We think that just like networking chips based on Atom and Xeon architectures eat into ASPs that FPGA and Xeon-FPGA hybrids will have an effect on the shipments and revenues of compute engines at Intel. However, in this case, the sale of FPGAs and Xeon-FPGA hybrids, like the 15-core Broadwell combined with an Arria 10 FPGA that Intel is sampling to hyperscalers now, will have a tendency to decrease the number of Xeons sold since some work that would have been done on Xeons alone will now be done on hybrids. (This is no different than a hyperscaler buying two 24-core Xeons for a premium rather than two servers Xeons of lower price points and lower core counts.) The idea here is to sell “Knights Landing” Xeon Phis to attack part of the hybrid CPU-GPU business that Nvidia has established with its Tesla accelerators and CUDA programming environment and use Xeon-FPGA hybrids to attack those parts that are not amenable to Xeon Phi. This strategy may or may not pan out, but it is, practically speaking, Intel’s only option unless it wants to create a GPU computing stack of its own that is compatible with CUDA. This seems highly unlikely, but boy would that sure be interesting. Even AMD might get involved in the lawsuits in that one. . . .

In the first quarter, Intel’s memory business was under water to the tune of a $95 million operating loss, which Smith said was due to the ramping costs on 3D XPoint memory, which will be available in Optane SSD form factors later this year, as well as startup costs relating to its Dalian, China 3D flash fab and a bit of a price war in the overall flash storage space among enterprise customers. So while Intel was able to push storage revenues up 6 percent to $537 million, it has had to invest for the future and lost some dough.

Intel has its reasons for not merging these businesses into Data Center Group – it wants to be able to tell a pure story for its server, storage, and networking chip business for now and these other businesses are settling in at the moment. Take a look at the last five quarters:

Intel did not count in the financial results for the four quarters of 2015 for Altera, since it down not own the company yet, and Altera did not report results for the quarter ending in December. We put these numbers in red in the chart above so you could see them in the revenue and operating income lines, but we did not add them to the Intel totals.

If you want to get a sense of Intel’s “real” datacenter business, you have to add in the new Altera FPGA business plus a good chunk of the IoT Group and most of the flash storage business. For the sake of argument, in the table above we are attributing half of the IoT Group revenue and operating profit to this hypothetical datacenter business for Intel and 90 percent of the flash business. If you do that, the datacenter business at Intel is larger than Data Center Group proper, and while not as profitable as Data Center Group as reported, it is still considerably more profitable than Intel overall.

The important thing is that Intel is determined to sell chips, motherboards, software, and other components wherever it can to make up for the PC shortfall and to keep its chip fabs warm. Getting good yield and driving down the price of a chip is a direct function of manufacturing volumes, and it is here that Intel can’t take its foot too far off the gas. Intel CEO Brian Krzanich was clear about the need to reinvest the savings from its layoffs back into these IoT, memory, and FPGA businesses to get them on better competitive footing that is akin to that it has with Xeons in the datacenter.

“Acting now enables us to increase our investments in areas that are critical to our future success,” Krzanich explained referring to the layoffs. “This restructuring program will allow us to expand our investments in the Data Center, Internet of Things, memory, and connectivity, even as we reduce our spending run rate by roughly $1.4 billion by mid-2017. This is a comprehensive initiative. It is designed to create long-term value by accelerating the fundamental, long-term change already happening at the company today. We will emerge as a more collaborative, productive team with broader reach and sharper execution, and we expect it to result in the highest revenue per employee in the company’s history.”

As for Data Center Group as reported, it looks like if 2016 resembles 2015 in terms of growth, then it should exit 2016 with around $4.8 billion in revenues and maybe half of that coming in as operating income during the fourth quarter. With the “Broadwell” Xeon D and Xeon E5 v4 processors out the door, Intel has to complete the Broadwell revamp with a Xeon E7 refresh and then it is just a matter of driving demand and meeting it. Hyperscalers and cloud builders are still growing, but enterprises are still sluggish, so it is hard to guess how it all might map out in 2016.

Intel wanted to own the server business when it started two decades ago, and now it wants to own the rack and everything in it, and Krzanich did not pull any punches about that.

“What we are trying to do is really provide top-of-rack to bottom-of-rack solutions that work together and bring performance across the whole rack,” he explained. “And that starts with Rack Scale Architecture itself, which is a very unique architecture that will allow people to build racks in a much denser and lower cost way, to silicon photonics for within rack communication. Then we have got 3D XPoint, and then you have our whole CPU architecture from networking, storage, up through server. We believe we are uniquely positioned to provide that whole rack viewpoint and have everything work together, and come together to bring performance that is just unbelievable. And what is key to really keeping our position is to own that, is to understand that whole rack from top to bottom.”

It is hard to argue with this logic, of course. The rack is, in essence, the new server, and the datacenter is the new rack. How long before Intel wants to own that? And will the ARM and OpenPower collectives, which are attacking on multiple fronts with serving, networking, and storage, have any success in breaking into datacenters that are crowded with racks that are increasingly Intel Inside? Companies want competition, but only if they get something more than 10 or 20 points of savings from one time off. Alternative architectures will have to offer a sustainable advantage to drive a sustainable business that can rival the one that Data Center Group has built.

Be the first to comment