Intel is the undisputed champion when it comes to computing in the datacenter, and it is looking to vanquish IBM’s Power processors from enterprise systems and supercomputer clusters and to keep the handful of ARM server chip upstarts at bay as they try to get in the datacenter door, too. And with the forthcoming “Knights Landing” massively parallel chip, which will be used as both a processor and a coprocessor for X86 systems, Intel is taking on Nvidia, which has carved out a good slice of compute work in HPC and deep learning with its Tesla GPU accelerators.

There are no new processor announcements coming from Intel at the ISC 2015 supercomputing conference this week, and indeed, none from IBM or AMD or Nvidia for that matter. Intel has been plenty busy in the past several months on the server front, so there is no surprise in this.

The company launched its “Haswell-EP” Xeon E5 v3 processors last September, and these are the workhorse engines used in two-socket machines. A special Xeon D chip from the “Broadwell” generation came out in March, aimed at single-socket machines for specific workloads at hyperscalers like Facebook and a roadblock of sorts to the rising ARM server collective. The high-end Xeon E7 v3 processors, technically known as the “Haswell-EX,” came out back in early May, and mostly compete against Power and Sparc processors in machines with four or more sockets. Intel finished off the Haswell rollout in early June with the special version of the Xeon E5 configured for lower-cost four-socket machines and a single-socket “Broadwell” Xeon E3 that takes its place beside the Xeon D.

The Broadwell Xeon ramp will begin in earnest at some point, but as far as we know, Intel is not planning to launch the flagship “Broadwell-EP” Xeon E5 v4 chips for some time. Many had been anticipating a launch at Intel Developer Forum in August, or perhaps at the SC15 supercomputing conference in November. There are some indications that there is some softness in the uptake of Haswell Xeon E5 systems right now – we will know more in a few weeks when Intel reports its numbers and server makers do, too – and it is therefore logical that Intel might push out the Broadwell ramp a bit to let Haswell pay for itself. It is not like the Haswell chips can’t compete against the current crop of Power8 from IBM, the Sparc T6 and M6 from Oracle, and the Sparc64-X from Fujitsu. (Not that these and a few other processors don’t have their advantages.)

It is fairly safe to say that the “Knights Landing” parallel processor from Intel will indeed be the most interesting thing to come to market before the end of the year, and not just because we like the HPC space but because the chip will, we think, find broad applicability outside of traditional simulation and modeling workloads where Fortran dominates.

Intel has been talking about the Knights Landing Xeon Phi for so long that you can be forgiven for thinking that it is already here. We caught sight of systems designed for Knights Landing back at the Open Compute Summit in early March and later that month divulged some of the secrets of the processor in a deep analysis piece on the processor. We have also speculated on the ramifications of the use of near and far memory in the Knights Landing implementation of the Xeon Phi.

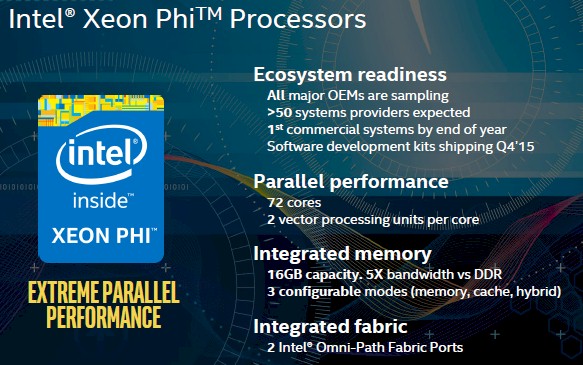

Among the many technical details that we have been able to nail down about Knights Landing, the one thing that Intel had not yet confirmed was the number of cores on the die. It turns out to be – drumroll please – precisely what had been rumored to be, and that is a whopping 72 cores across its over 8 billion transistors. That is a lot of transistors for a single chip, regardless of architecture, but it is the transistor density that we can expect as Intel continues to shrink through 14 nanometers to 10 nanometers with its regular Xeon processors.

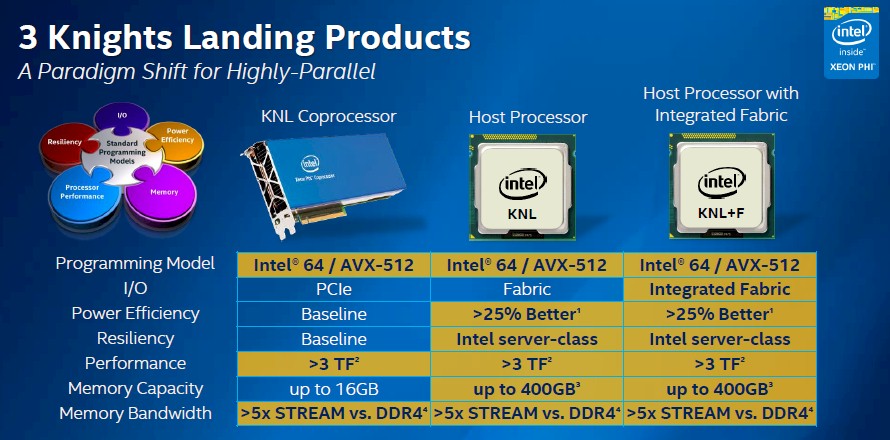

The other piece of information that Intel confirmed in its ISC15 briefings is that the Knights Landing, when implemented as a standalone processor, will come with two ports of Intel’s Omni-Path interconnect on the package. This is precisely what we had been speculating based on the fact that many HPC shops have dual-rail networks for redundant pathing and resiliency.

Intel had already discussed the three different variants of the Knights Landing chip that it would deliver in March, and it bears repeating:

The Knights Landing chip is expected to deliver at least 3 teraflops of double-precision floating point performance and twice that at single performance – that predictability will be a big asset, because GPU accelerators often are better at DP or SP, depending on the make and model. It is not clear what clock speeds or how many cores will be active to attain this performance level with Knights Landing, and it is quite possible Intel itself is not sure yet. The chip will have up to 16 GB of high bandwidth memory (HBM) on the package (the near memory) and another 384 GB of DDR4 memory (this is the far memory) for data and applications to frolic in. The DDR4 memory will deliver 90 GB/sec of bandwidth into and out of the Knights Landing’s cores, which have two vector math units each, and the near HBM memory will deliver more than 400 GB/sec of memory bandwidth. This will no doubt lead to a much bigger leap in application performance than the move from the current 61-core “Knights Corner” Xeon Phi cards, which were rated at a little more than 1 teraflops at double precision, to the Knights Landings, which have triple that raw floating point performance.

What we now know is that there will be SKUs with up to the full 72 cores, and that means Intel must be pretty confident about the 14 nanometer process that it is using to etch the Knights Landing chips.

“A lot of what we have been doing over the past year is ecosystem readiness,” explains Charles Wuischpard, vice president and general manager of the Workstations and High Performance Computing division in the Data Center Group at Intel. “We have been sampling with the OEMs, getting the system designs ready, and we have over 50 system providers expected and will be shipping our first systems by the end of the year.”

The hardware is always the easy part when it comes to a new architecture, and that is one of the reasons why with the Knights Landing chip, Intel is making it a full-blown processor, with its own main memory (albeit tiered) and the ability to run Linux and Windows Server like any other Xeon. The Xeon Phi is no longer just Xeon in name, but in functionality. That said, the software is still a bit tricky, and Wuischpard conceded as much and said Intel would do better

“If I had to critique out SDKs back with Knights Corner, I think we did not do enough of a good job at the developer level with making sure the product was easy to use out of the box and give a very intuitive experience,” he says. “We are looking to change this this time and have this be an iPhone experience for Knights Landing. It will be a good package with scripts, sample code, and the like. Right now, the problem is that we have more demand than we anticipated with these development kits and we are sorting through the priorities.”

As part of the ISC update, Wuischpard said that Raj Hazra, who has been general manager of the Technical Computing Group within Intel’s Data Center Group, was now also put in charge of the Enterprise Computing unit at the company. The enterprise and technical computing units represent 70 percent of the revenues that Data Center Group – which should be running at a $20 billion annualized clip by the end of 2016 if current financial trends persist. (See our detailed analysis of Intel’s Data Center Group financials here.)

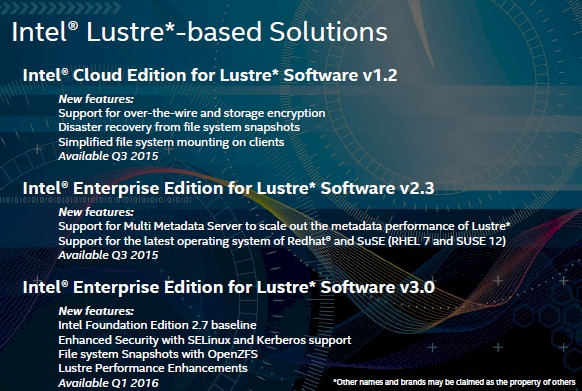

He also said that are part of recent reorganizations, the Lustre parallel file system that Intel got a few years back when it bought Whamcloud and got the key team of original Lustre coders and support specialists, had been moved from Intel’s Software Group over to the technical computing side. Wuischpard laid out a roadmap for the cloud and enterprise editions of Lustre, thus:

Wuischpard said that Intel was increasing its investments in Lustre and that as was the case with the forthcoming Xeon Phi, it wanted to make Lustre more enterprise-grade and easier to use.

Isn’t Intel using a variant of Micron’s Hybrid Memory Cube(HMC) that they’re calling MCDRAM on their EMIB package as opposed to HBM which is on an interposer?

I keep using HBM as a generic term. Sorry about that. But yes, it is a variant of HMC that has its own interface, as we disclosed back in March. High Bandwidth Memory–it is like calling a brick a Hard Red Stone.

Any idea what the price range will be for the KNL CPU or co-processor?

None whatsoever. But it is interesting to contemplate.

What I would love to see is a xeon phi that is pc compliant

instead of buying new mobo cpu and ram just throw in one of these 72 core babies.

I think it will blow gaming into and out of the water with what can be currently offered.