Incoming chief executive officer and long-time Intel employee Pat Gelsinger is talking the helm of a chip company that has plenty of issues to sort out, but there is some good news as Intel reports its financial results for the fourth quarter of 2020 and Gelsinger gets ready to take over.

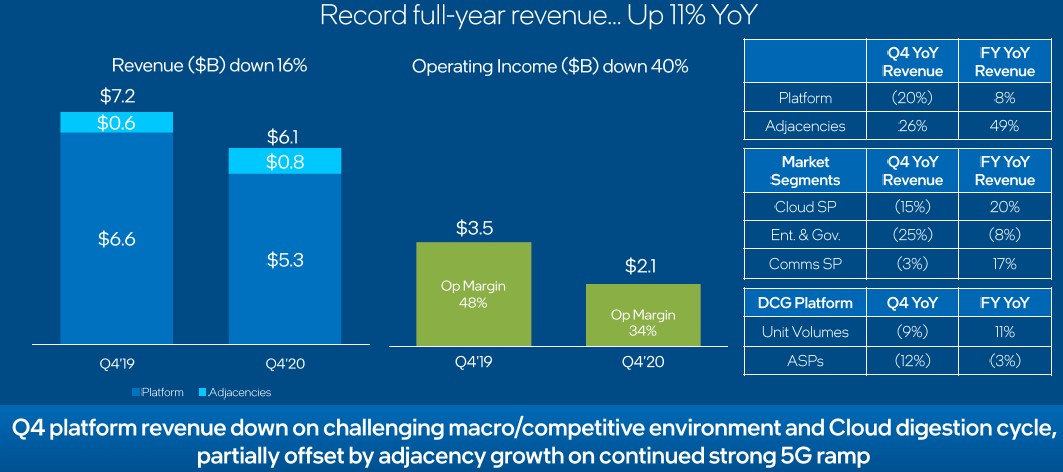

First and foremost, from the point of view of the markets and products we follow here at The Next Platform, the collapse of revenues for the Data Center Group, which the company had been projected by Intel to fall by 25 percent in the final thirteen weeks of 2020, did not happen and the company merely declined by 15.6 percent to $6.01 billion. However, operating profits for the Data Center Group fell by 40.2 percent to $2.08 billion, or 34.1 percent of revenues, which is for the second quarter in a row where operating margins were well below the usual average for Data Center Group.

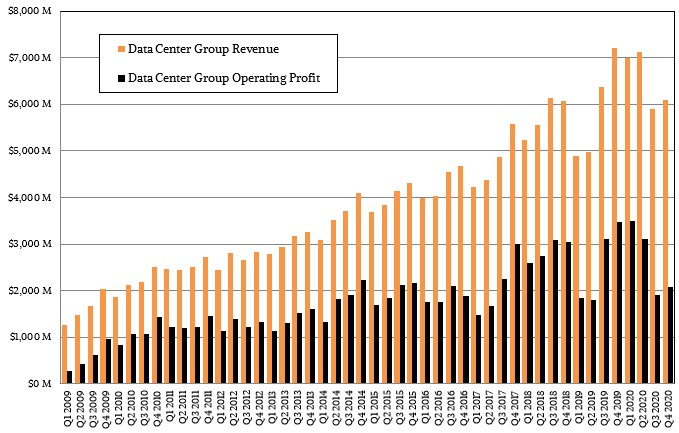

Part of Intel’s problem is that hyperscalers and cloud builders have their own cycles and sometimes they all line up to drive revenues and profits higher and sometimes they all take a pause to digest the servers they have already consumed. You can see this reflected in the revenue and operating profit figures for Data Center for each quarter since the Great Recession:

Back in the days when Intel set the pace and the IT organizations, including the hyperscalers and cloud builders, followed along, the fourth quarter was usually the biggest revenue generator, which has been true of the IT organizations of the world as long as anyone can remember because of the nature of the calendar year that most companies hew to. Meaning, one that ends in December. It is amazing, really, how regular Intel’s pattern for Data Center Group was between 2009 and 2015, and part of that was due to the lack of competition from AMD in servers and part of that was also due to the relative regularity of Xeon processor announcements during those years. Relative weakness set in during the first and second quarters of the year after that, and Intel’s own product delays as well as the buying patterns of the Super 8 started making the fourth quarter relatively weak in 2019 and now the third and fourth quarters were relatively weak in 2020. If Intel can really ship its 10 nanometer “Sapphire Rapids” Xeon SPs in the final quarter of this year, as it now says it can, then maybe Q4 2021 won’t be so weak, but we suspect that volume shipments will really hit for Sapphire Rapids in early 2022, so maybe there will be a bit of improvement in Q4 2021 and a really exceptional Q1 2022.

We shall see.

In a conference call with Wall Street analysts going over the figures, incoming CEO Gelsinger shed a little light on the 7 nanometer subject, but did not fully clarify just how much of the chip production in 2021 and 2022 would be offloaded to rival foundries Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp and Samsung Electronics. Gelsinger bought Intel a little more time, and reasonably so considering that this decision predates his move to Intel and will determine how Intel is judged under his watch starting in three weeks.

“I had the opportunity to personally examine progress on Intel’s 7 nanometer technology over the last week,” Gelsinger explained on the call. “Based on initial reviews, I am pleased with the progress made on the health and recovery of the 7 nanometer program. I am confident that the majority of our 2023 products will be manufactured internally. At the same time, given the breadth of our portfolio, it is likely that we will expand our use of external foundries for certain technologies and products. We will provide more details on this, and our 2023 roadmap, once I fully assess the analysis that has been done and the best path forward.”

As to what the precise nature of the issue was that pushed out the 7 nanometer products – which was divulged to Wall Street back in July 2020 and characterized as pushing out 7 nanometer chips from Intel by around six months – outgoing CEO Bob Swan, offered the following explanation.

“In July, we highlighted a challenge with our 7 nanometer technology and started a process to improve it, while evaluating the best approach for our 2023 product lineup,” Swan said. “Since that time, we have made tremendous progress on our 7 nanometer technology. When 7 nanometer was originally defined, the flow contained a particular sequence of steps that contributed to the defect issue we discussed in July. By re-architecting these steps, we have been able to resolve the defects. As part of this work over the last six months, we also streamlined and simplified our 7 nanometer process architecture to better ensure we will be able to deliver on our 2023 product roadmap. The inline data we have been collecting and our pipeline of proven yield development projects gives us confidence in our ability to deliver on our commitments going forward. At the same time, as Pat mentioned, we will continue to leverage the relationships we have developed over the years with our external foundry partners and we believe they can play a larger role in our product roadmap given our disaggregated designs. Once Pat has had a chance to join, he’ll further assess our analysis and drive the final manufacturing decision for our 2023 CPU products. Therefore, we will communicate that decision soon after he takes over, but not today.”

Sorry folks, this is going to take a little longer. But Intel seems confident that it can put its manufacturing house in order and get back to being the integrated device manufacturer that Intel co-founders Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Andy Grove literally taught Gelsinger how to create in his three decade career at the chip maker. If anyone can get Intel back on track, Gelsinger is the one. We strongly suspect that Intel is not going to pivot hard, as we contemplated as a series of possibilities earlier this week, but stay the course. Gelsinger is pulling a Gerstner and keeping the band and the brand together, as that famous CEO did for Big Blue two decades ago when it ran up onto the rocks.

Swan confirmed that the Sapphire Rapids Xeon SPs, which are expected to support DDR5 memory and PCI-Express 5.0 peripherals and which are based on the updated SuperFIN 10 nanometer process from Intel, are “broadly sampling” to customers. “We expect production qualification of Sapphire Rapids at the end of 2021,” Swan added. No word was given about the 7 nanometer “Granite Rapids” Xeon SPs, which were slated for delivery in early to middle 2022 and as of last summer had been pushed to sometime in the first half of 2023, or the “Ponte Vecchio” Xe discrete GPU accelerators that were due early this year and now are coming in late 2021 or early 2022, probably with a mix of Intel and foundry partner silicon. Sapphire Rapids CPUs and Ponte Vecchio GPUs are the main compute engines in the much-delayed “Aurora” exascale-class supercomputer to be built by Intel and installed at Argonne National Laboratory. This machine was originally slated for delivery in 2018, based on “Knights Hill” parallel CPUs with fat vector engines and a 200 Gb/sec Omni-Path 200 interconnect.

We can only imagine how annoyed Argonne is, particularly with the exascale machines going into Oak Ridge National Laboratory and maybe even Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory ahead of it.

As for why Q4 2020 was not as bad as it might have looked three months ago, perhaps the current “Ice Lake” Xeon SP chips are not getting as hammered by AMD’s “Milan” Epyc 7003 series as we might expect. Hyperscalers and cloud builders might be buying more Intel chips than even Intel expected in the past several months. It is hard to say if that holds. But they might be on another buying spree in the first and second quarters of this year, and both Intel and AMD could see good growth, with AMD making market share gains but still not hurting Intel as badly as you might expect.

One reason is the adjacencies outside of server CPUs, server chipsets, server motherboards, and the occasional servers that make up Data Center Group’s sales, and which, we think, includes a fair amount of compute aimed at 5G wireless networking gear. Some of the 5G radio access network (RAN) revenues go into Data Center Group because they have Xeon CPUs in them, some goes into the Programmable Systems Group because they also have FPGAs in them. These products, added to switches and network interface cards and various wireless compute products, now comprise a $6 billion business across Intel for all of 2020, up around 20 percent from sales levels in 2019. Intel claims to have 40 percent share of this 5G RAN business – a market share goal it reached two years ahead of schedule.

You can see it in the Data Center Group numbers, and it helped cushion the blow as enterprises and governments as well as hyperscalers and cloud builders slowed their server consumption.

In the fourth quarter, the core Data Center Group revenues – for server stuff – came in at just a hair under $5.3 billion, down 19.6 percent. But those adjacent businesses counted in the Data Center Group total, which we think will be broken out as a separate networking business when Gelsinger comes in and SK Hynix buys off the NAND flash business, came to $791 million in sales, up 26.4 percent. It doesn’t fill in the server pothole, mind you. And once it is broken out as a separate business unit, it never can. But it is helping the overall Data Center Group numbers now for sure. The adjacent businesses in Data Center Group grew by 49.4 percent for all of 2020, to just over $3 billion. This is now material.

And that 5G RAN business probably helped the Programmable Solutions Group FPGA business, too, which booked $422 million in sales, down 16.4 percent, and could be a bigger factor going forward as network equipment suppliers go for the latest FPGAs for these baby datacenters with an antenna.

Just out of curiosity: do you have any names and sales numbers for those Ice Lake customers buying stuff in Q4? With the official launch still some time to go, those early shipping deals must be huge to help the bottom line.