Not everybody is a hyperscaler or large public cloud builder, and no two companies are happier about that than Dell Technologies and Hewlett Packard Enterprise, the two largest original equipment manufacturers in the world for servers and storage and also the two companies that chased plenty of sales at these webscale datacenter operators in years gone by but which have learned, of necessity, to walk away from deals where they can’t make money or even lose money.

The two companies gave us a glimpse into their respective datacenter businesses in recent days, and we plowed into the figures to try to get a sense of what is going on in the enterprise, basically taking a snapshot before whatever effects of the coronavirus outbreak hit the server market. Even without Covid-19, both Dell and HPE were struggling, and that is not a good sign. We aren’t sure what it means yet, but Intel also reported that enterprise spending for its Data Center Group was soft, down 7 percent in its most recent quarter, and again that was before Covid-19 started slowing down sales of just about everything but disinfectant, facemasks, flu medicine, and ibuprofen.

Because Dell is the dominant OEM seller of both servers and storage, we will cover it first. Dell’s fiscal year ends in January each year, and after it was done taking itself private and acquiring all of enterprise server virtualization juggernaut VMware and its EMC enterprise storage juggernaut parent, Dell rejiggered its financial presentations to include these businesses in a consolidated format.

It is immediately obvious, of course, that Dell is a very large company and is indeed the largest IT supplier in the world. This was an aspiration that Michael Dell, the company’s founder, has had for at least as long as we have been watching the glasshouse, and say what you will, but Dell did it. But what is also glaringly obvious is that this business has to work hard to be profitable given all of the grief Dell gets from other OEMs like HPE, Lenovo, Cisco Systems, Inspur, Sugon and the original design manufacturers like Foxconn, WiWynn, Inventec, and others as well as the in-betweener Supermicro. (The lines between OEM and ODM are blurry, and Dell used to have a very large custom server business of its own before Facebook started the Open Compute Project.) As we have said before, the systems business and the storage business is very cut-throat, and we are thankful that companies step up to the plate and do the job each and every quarter because someone has to build this stuff. But the margins on hardware are nothing like what we used to see in the 1980s and 1990s, or even the 2000s, and what margins there are in systems end up going mostly to Intel with some sent to the makers of DRAM and flash and GPUs and some sent to Microsoft and even less sent to Red Hat.

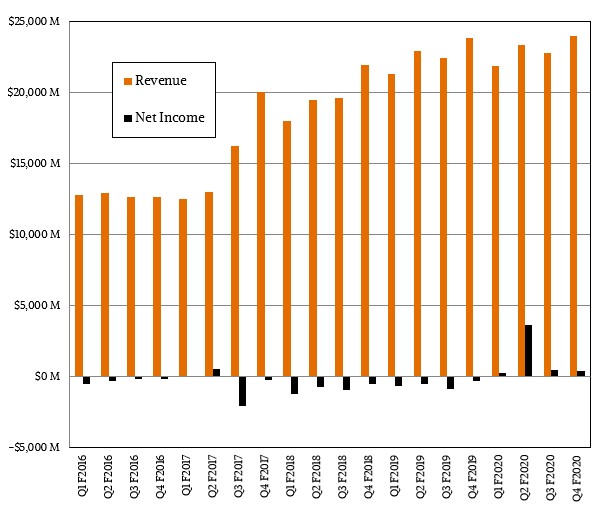

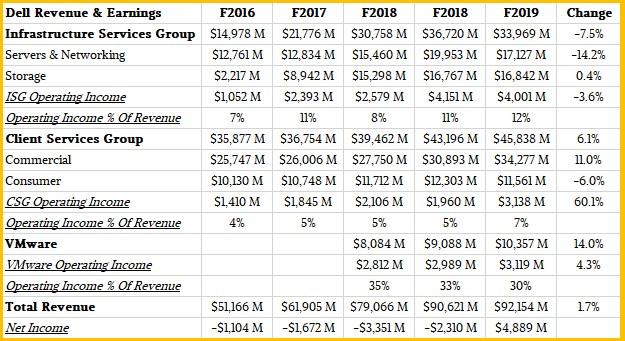

In the fourth quarter ended on January 31, Dell’s revenues were just a tad over $24 billion, up eight-tenths of a point compared to the year ago quarter, but it flipped to a net income of $408 million from a loss of $299 million. This is progress indeed, considering the softness in server and storage sales. The Servers and Networking division posted sales of $4.27 billion, down 18.7 percent year on year against a very tough compare when Dell kissed $10 billion in system sales in Q4 F2019. Jeff Clarke, vice chairman and chief operating officer at Dell, said in a conference call with Wall Street analysts that the server market was soft in China (due in part to the corona virus we think given the end of January period), but that large enterprises in both the United States and Europe also pulled back the reins on system spending as well. On the storage front, sales of the vast portfolio that Dell has amassed dropped by 3.2 percent to $4.49 billion, and Dell added that it would be rebranding its storage products under the “Power” brand by May. (We presume they meant PowerStore to match the PowerEdge server brand and PowerConnect switch brand.) In the past two years, Dell has gone from 80 distinct storage products down to 20, and Clarke called out hyperconverged infrastructure (HCI) as a key driver of growth in the coming year along with core enterprise storage and data protection hardware and software.

All told, the Infrastructure Services Group had $8.76 billion in sales, down 11.5 percent, and an operating income of $1.11 billion, off 12.1 percent and comprising 12.7 percent of revenues.

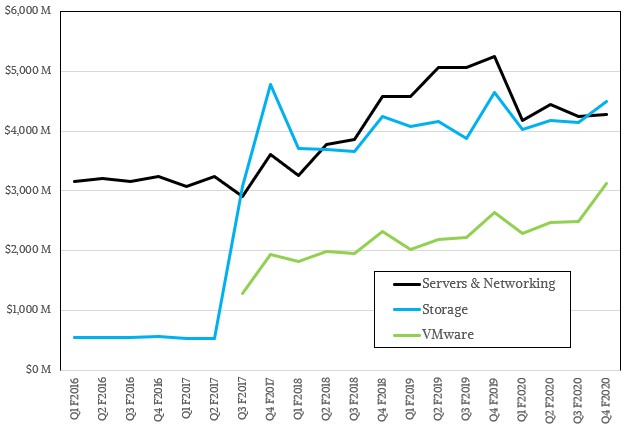

The picture for the full year is a little different for ISG, as this summary table shows:

And here is the data going back to fiscal 2016 that shows the ups and downs of the datacenter business groups at the new and embiggened Dell:

“Server and networking revenue declined in fiscal year 2020, but profitability was up as we didn’t chase unprofitable server deals in a down market,” explained Clarke. “Our long-term server share trajectory remains strong. We are winning in the consolidation.” Clarke added that Dell was the number one supplier of “mainstream servers” for seven quarters in a row, which we presume he means enterprise and SMB class PowerEdge machines and not custom or semi-custom iron, and that market watcher IDC reckoned that this mainstream server sector would see growth of 3.3 percent in calendar 2020 and then said Dell believed it would outpace this market. This would be driven by more expensive iron and particularly that which runs AI workloads, which are heavy on everything except the irony. Clarke said that demand in China was down around 35 percent but the rest of the world was down only 5 percent. The real softness outside of China was in large enterprises in North America, who might have been catching wind of coronavirus early and tapping the server spending brakes.

An interesting tidbit: In the call, Clarke said that Dell has about 30,000 unique server buyers every quarter, and that only about half of them buy storage (presumably he meant external storage) from Dell. Moreover, Dell has about three times as many server buyers as storage buyers, so the opportunity to sell across the former Dell and former EMC silos is still quite large. Simplifying and updating the storage products this year is part of the plan. To try to boost ISG sales, both for servers and storage, in fiscal 2021, Dell has invested over $1 billion in “capacity and coverage” in the past two and a half years to chase more deals. And Clarke thinks, with customers digesting the large numbers of servers they bought in the prior two years, there is a new consumption wave coming this year.

From Clarke’s mouth to those 240,000 customer ears. . . .

As you can see, VMware continues to be the profit engine at Dell, with sales up 18.5 percent in fiscal Q4 to $3.122 billion and operating profits up 17.7 percent to a very healthy $1.03 billion (32.8 percent of revenues). VMware closed the acquisition of Pivotal in the fourth quarter, which VMware acquired years ago, spun out, and then reacquired. Pivotal is, of course, the provider of the Cloud Foundry application framework and is going to be delivering an integrated Kubernetes platform, which we expect to be hearing more about in the coming weeks.

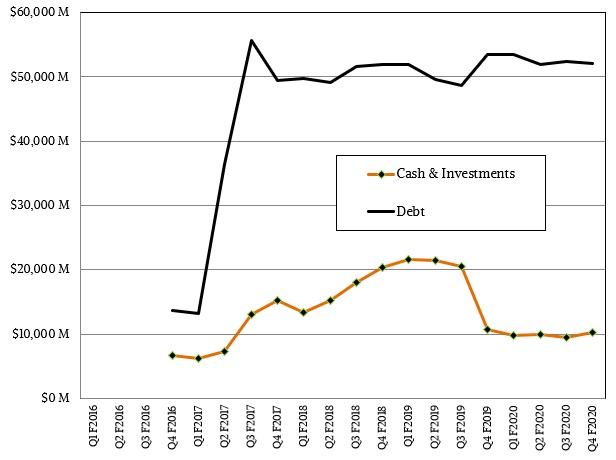

Even with all that revenue and the improving profits, Dell’s debt load is still high after acquiring EMC (and therefore VMware) a few years back and then taking private a few years after that. About a third of Dell’s cash is parked in VMware, and it spent $11 billion at the end of 2018 as a special dividend relating to its going public again through a tracking stock related to its ownership of VMware that landed Dell back on the New York Stock Exchange as a public company. VMware still reports separate financials, but we are not getting into those today except for the mention above and to point out that vSAN virtual storage bookings were up around 15 percent and NSX virtual networking bookings were up over 20 percent. (We will be drilling down into VMware more next week, when the company talks more about its strategy for the future.)

The point is, Dell has a lot of debt still, which is one of the reasons why it is selling off its RSA Security divisions, which is one of the big acquisitions that EMC made back in 2006 for $2.1 billion after it acquired VMware in 2003 for a mere $635 million just before VMware was getting ready to go public. Dell is selling RSA Security for $2.1 billion, so the Dell collective is getting its bait back and got all the RSA revenue for the past 14 years for free and now it gets to use the funds to pay down more debt.

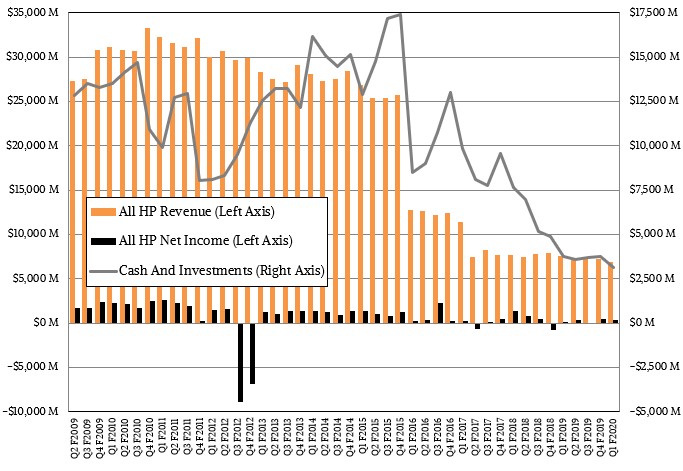

Now, let’s have a gander at Hewlett Packard Enterprise. In the quarter ended in January, HPE posted sales of $6.95 billion, down 8 percent, and net income was up by 88.1 percent to $333 million due mostly to cost cutting maneuvers and with a small increase of research and development spending (which now includes Cray). HPE has $3.17 billion of cash in the bank, which is respectable given its size. Here’s the HPE revenue and income chart over time:

As is immediately obvious, HPE in its older Hewlett-Packard incarnation that included PCs and printers as well as some systems and PC software and a sizeable enterprise services (outsourcing and systems integration) business, and was in fact larger than the new and embiggened Dell. HPE had huge writeoffs from its ill-fated Autonomy software acquisition, and it has sold off its enterprise services and most of its software businesses as well as spinning off PCs and printers into HP Inc, and now it is considerably smaller. And Dell’s core systems business – servers and storage together – at $8.76 billion is also around 70 percent larger than HPE’s $5.67 billion in the most recent similar quarter. That is thanks in part to Dell becoming the biggest shipper of OEM servers in the world, passing HPE seven quarters ago, as HPE started walking away from deals where it could not make money – something Dell is also starting to do. It also comes from buying EMC, the largest enterprise storage supplier, and having a business that is about five times larger than the storage array business of HPE.

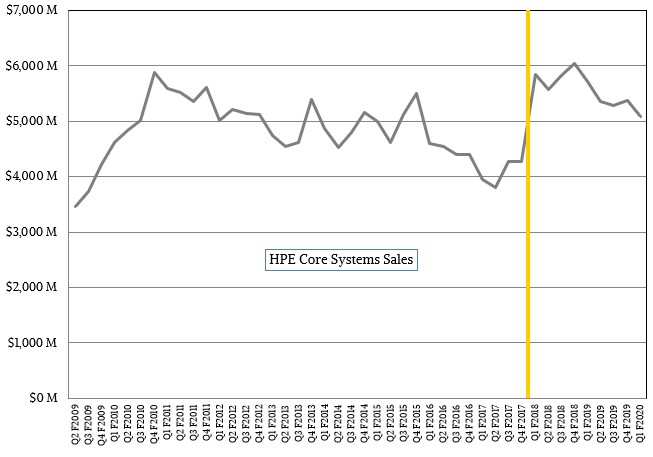

We have been tracking the HPE core systems business over time in its various incarnations and presentation styles, and here is what it looks like if you shake all the non-datacenter stuff out:

That orange vertical line shows the demarcation between the older ways of classifying servers and storage (which did not include services, systems software, or maintenance) and the new way announced in February and backcast for nine quarters. Relatively new chief executive officer Antonio Neri has rejiggered the company’s financial reporting categories to reflect the business in the wake of the acquisition of Cray and the breaking up of the Pointnext services category that frankly no one really understood very well anyway.

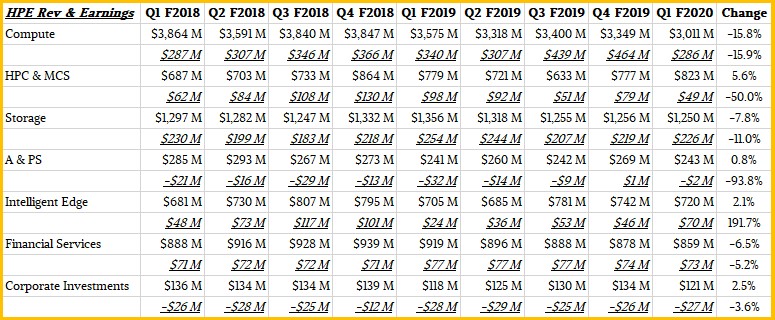

In the new categorization, the Compute division sells rack, tower, and blade servers bearing the ProLiant brand. The HPC & MCS division is, as the abbreviations suggest, the High Performance Computing and Mission Critical Systems lines. The HPC machines are the Cray XC and CS lines as well as the Apollo lines; the Apollo machines are replacing the CS machines in the new HPE lineup, and the SGI UV3000 and UV300 NUMAlink machines have been merged with the Superdome X NUMA boxes that HPE created itself to create a new line of fat NUMA boxes, called Superdome Flex, aimed at enterprise and data analytics workloads in the MCS division and sit alongside the Superdome X machines that support Linux, Windows Server, and OpenVMS. All of these machines are arguably about high performance, in one way or another, and hence belong together. That is not to say that there are not clusters of ProLiant servers that are being used as HPC machines or even AI engines when gussied up with GPUs or other kinds of accelerators. All of the break/fix maintenance and systems software for these machines are included in their revenue streams. The Storage division includes all of HPE’s storage arrays and HCI wares, again including the support and systems software, and the Advisory and Professional Services division does just what it says it does and was bundled into Pointnext previously. The Intelligent Edge business is still largely made up of Aruba hardware and software, but not includes datacenter instead of being shoved into Compute. Financial Services is still, well, financial services.

Having gone through all of that, here is what the last nine quarters of HPE’s numbers look like under the new classifications:

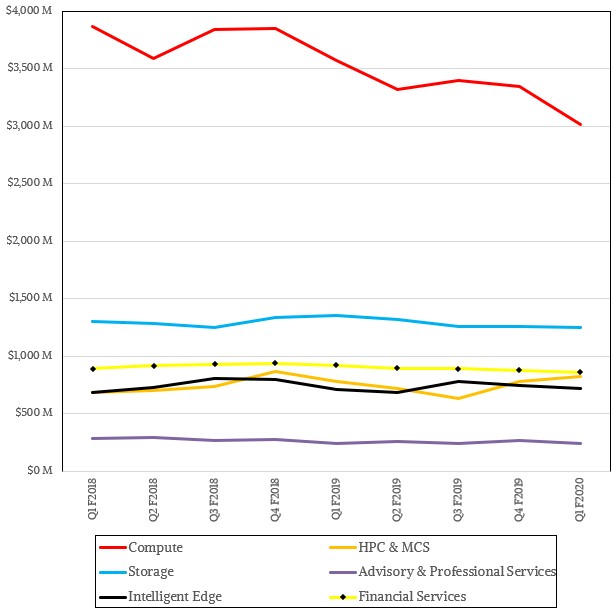

And here is a chart showing the divisions:

Aside from the general trend bending downward slightly in the Compute business (again, mainly ProLiant servers), the other lines are amazingly flat. So much so we checked them three times just to make sure. The services on Storage and Compute help smooth out the curves a bit.

But without a question, demand in the January quarter was impacted by a bunch of issues, and Neri didn’t dodge it. “Our Q1 revenues were impacted by a number of factors,” Neri explained to Wall Street analysts in a call going over the numbers. “First, like many of our peers, we continue to see uneven and unpredictable demand due to macro uncertainty. This has resulted in longer sales cycles and delayed customer decisions. Second, commodity supply constraints disrupted our ability to meet our customers’ demand this quarter, particularly in our Compute and HPC businesses. Additionally, the outbreak of the coronavirus at the end of January impacted component manufacturing, resulting in higher costs and backlogs. In both of these cases, we have established specific mitigation and recovering plans with each of our suppliers.”

The net effect of all of this is that HPE is cutting $300 million from its free cash flow for fiscal 2021, which is now set in the range of $1.6 billion to $1.8 billion.

There were some bright spots in the HPE Compute business. If you take Tier 1 clouds in China out of the mix, unit shipments of ProLiant machines were up “in the mid-single digits,” according to Neri. While Cray has won some big deals that will eventually come to the top line at HPE, that is from one to two years away and there is no guarantee that these big exascale systems will have high profits for HPE. That said, the HPC & MCS division had 6 percent growth, and Tarek Robbiati, chief financial officer at HPE, said that the HPC business – presumably dominated by all the recent Cray deals – had won over $2 billion in business that would be booked between now and 2023. How that revenue will stream in remains to be seen, and it is also unclear how much HPE can bring to the bottom line. But obviously HPE can buy CPUs and GPUs at higher volumes and lower unit prices than Cray ever could, and that should help make what used to be Cray more profitable. That means operating income will rise for the HPC & MCS division.

So not only did the $1.3 billion acquisition of Cray by HPE last September fulfill the goal of former chief executive officer Peter Ungaro to make Cray into a $1 billion and growing business, but it might even make that Cray business more profitable than it could ever have been even as it expands its revenue footprint again, perhaps to $2 billion. It’s hard to says for sure, but what we do know is that SGI and Cray survived for decades and didn’t really profit that much or that often because HPC is a tough, tough business with the most demanding compute, storage, and networking challenges and the most stingy budgets even if they are big. And HPE, in its many guises, has tried to have a datacenter business that was as profitable as that of IBM, which has had its own revenue and profit growth issues in the past decade.

Being an OEM is hard. Be grateful someone is still doing the job of engineering and building machines and trying to make it up in volume. It is often one of those thankless jobs. And if the OEMs stop, you will be thrown to the tender budgetary mercies of the clouds – and that is going to be truly expensive.

On that chart for HP it’s fairly obvious where the divestiture/split point between HP enterprise and HP Inc occurred. And that’s probably easy to spot but HP into HPE and HP Inc needs to have top and bottom bifurcated charts so the split up can be properly gauged. And that’s because I’m rather fond of breakups as they tend to increase the value of both new entities over time. Just look at the Standard Oil Octopus and Old John D. sure became richer after that forced breakup that resulted of that once monolithic Oil entity being split into 8 somewhat better competing smaller interests for a while.

That better fair market competition positioning has mostly disappeared in the Oil Industry the same way that it’s disappeared for the Phone/telecom industry that was broken up only to see consolidation reemerge as markets have once again become more consolidated.

And HPE gobbling up Cray and Xerox looking to gobble up HP Inc. Well that’s just more depressing news in this new Gilded Age of technology Trusts that has developed over the past 40-50 years. The Data Center and mostly 2 main players and really that’s not good news there either.

In the longer term I’m less worried about Covid-19 and more worried about consolidation in the Server/HPC OEM market place/other markets as well. As all that is savings related to the renewed AMD and Intel server/HPC market CPU/processor competition, or even the AMD and Nvidia GPU Server/HPC GPU accelerator competition, that produces savings via price/performance competition may not be all good news. And all that savings may not be passed on to the end users of that server/HPC equipment if the overall Server/HPC OEM market place competition is reduced because via too much OEM consolidation.

There are more giant markets that are mostly dominated by 2 very large players intermixed with many too small market share players that really lack a competitive economy of scale to properly compete with the largest players. And that’s just another downside to market consolidation that at some point in time may have to be forcefully reduced or fair market competition will suffer. And where competition suffers innovation and longer term market health suffer as well.

That T-mobile and Sprint merger, much to the chagrin of many US states’ attorneys generals, and even more consolidation in other markets with 2 giant players and many smaller players. And HPE and Dell and the many other markets with only 2 main players and that’s not looking healthy except for some limited shareholders and there appears to be no end in sight until some breaking point is reached and some new crash putting an end to the extended prosperity that may not have been, in the end, based on sound sustainable policies over the last years since most recent recession.