No platform can be everything to everybody. And while there are plenty of organizations that operate at scale who create their own platforms, often using best of breed components, there are some that – perhaps because of the experience of constantly cobbling together systems into platforms – just do not want to do the experimenting and testing and weaving. They want to buy a platform.

This is how Windows Server and Enterprise Linux grew from operating systems into platforms in their own right for their respective owners, Microsoft and Red Hat, and this is also the road that hyperconverged storage pioneer Nutanix ended up on when it sought to “band the SAN” from the datacenter with its hybrid virtual compute and virtual storage platform, which it started to build in 2009 and first delivered in 2011. A few years back Nutanix added its own Acropolis implementation of the KVM hypervisor, which let its customers stop paying VMware for ESXi and its many add-ons and reinvest that savings back into Nutanix software. The Nutanix stack has had many names over the years, but the company has settled on the Acropolis brand finally and has added a pantheon of services to it over the past five years, most notably an implementation of the Kubernetes container orchestration environment called Karbon (an homage to the idea of carbon copying containers) that came out last year and which was recently updated.

It has been a while since we took a hard look at Nutanix, so we used that Karbon update as a reason to dive back in and see what Nutanix is up to and how it is doing.

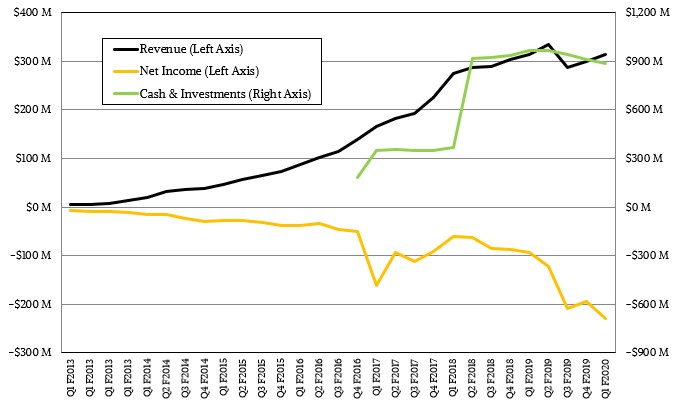

Let’s start with the money, since we have not analyzed the financials of Nutanix in quite some time. On a lot of metrics, Nutanix is doing quite well, especially considering how VMware came on really strong starting in 2015 with its vSAN virtual storage to compete against Nutanix and how the latter company is shifting its business model from selling appliances that bundle in its Acropolis stack or licenses to it for other iron to selling subscriptions for software that runs on selected iron from OEMs and ODMs. There is a certain amount of competition from Hewlett Packard Enterprise with Simplivity and Cisco Systems with HyperFlex and Microsoft coming on stronger with its Azure Stack HCI (which runs Storage Spaces Direct virtual storage atop Windows Server and Hyper-V), and while IBM’s Red Hat unit is a late entrant with its Hyperconverged Infrastructure for Virtualization, this can slide underneath its OpenShift implementation of Kubernetes and give Red Hat a stack that is analogous to the one that Nutanix has built with Acropolis with Karbon.

There is not very recent market share data available, but Smith cites a report from last year for the first quarter of calendar 2019 from the analysts at Gartner that showed the overall market for HCI software – not including appliance revenues from any of the players, but particularly for Nutanix and VMware, which both sell appliances – was up 31.8 percent to $359.9 million, with Nutanix having 50.8 percent share at $179.8 million for Acropolis and its add-ons and VMware coming in second place with $153 million in revenues for vSAN alone. By the way, Nutanix started off with VMware being its supported server virtualization layer, and now has shifted about half of its customer base to its own Acropolis implementation of KVM.

Juggling Many Transitions

All of these competitive forces have been there for many years, but they really came to a head in the past three years, and the revenue coming into from Nutanix reflects this as well as the very difficult shifts from licensing to subscription sales and from appliances to software sales that the company has undertaken to transform the company for the long haul and to be friendly to both on premises and cloud deployment models.

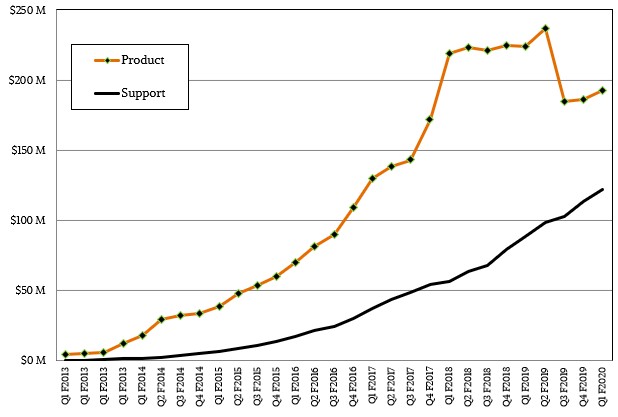

As you can see from the chart above, something clearly happened with product sales starting at the end of fiscal 2018 (July 2018 on the calendar), when revenues stalled, and as the quarters went on they flattened and then, in Q4 fiscal 2019 (the quarter ending in April of that calendar year), went into decline. It is hard to separate out the change to subscription pricing from other factors, but the good news is that support revenues kept growing, albeit at a diminishing rate over time, and filled in almost all of the gap. It is hard to imagine managing that transition better, at least at the top line.

The other good news for Nutanix is that customers keep coming back for more even as the customer base is itself growing by somewhere between 800 and 900 customers per quarter, on average, and as the first quarter of fiscal 2020 came to a close in October 2019, 73 percent of billings were represented by subscriptions, and 69 percent of revenues that were recognized in that quarter were for subscriptions. (Some subscriptions have a term of one between one and five years, sometimes longer, with the average being 3.6 years, and the revenue for those subscription contracts has to be reckoned and spread out over that time in very precise ways that the accounting profession and the US Securities and Exchange Commission are both very interested in normalizing across industries.) Nutanix was projecting that by the final quarter of fiscal 2020, which will end in July this year, subscriptions will be 75 percent or more of billings; it did not project what portion of revenue would be subscriptions, but probably not far form that number given the current trend. At some point, all revenue will be subscriptions and Nutanix will be through that transition.

“We are getting through what Dheeraj Pandey, our founder, calls the messy middle,” Greg Smith, vice president of product marketing, tells The Next Platform.

The revenue curve for products, shown above, sure looks like Nutanix is through that messy middle and is now growing again after a pretty steep decline caused, in large part, by that transition.

If that product revenue line had continued to drop in the past three quarters, this would have been disconcerting. That sharp rise at the end of fiscal 2017 and early fiscal 2018 must have been fun, but the sharp decline in Q3 of fiscal 2019 must have been a little nerve racking. This is mitigated by the fact that Nutanix exited the quarter with $429 million in short-term deferred revenue and $546 million in long-term deferred revenue in the bank; this deferred revenue was up 39 percent year on year. This is the benefit of changing to that subscription model.

There are other encouraging trends. The customer count at Nutanix as Q1 fiscal 2020 came to an end was 14,960, up 30 percent year on year, and the company had 840 of the Global 2000 among its customer list. Across those Global 2000 customers, the lifetime purchase multiple – how much did a company spend in the aggregate compared to the first contract it did with Nutanix – was 12.5X. Across the base, that multiple is lower at 11.7X, but importantly it is not a lot lower and the smaller customers are behaving like the larger ones – the scale is fractal, in other words. And across the entire base, that multiplier effect is growing; three years ago, when Nutanix first started tracking this data, the multiplier was only 7X across the entire base. So given all of this, it is not surprising that 76 percent of bookings in Q1 fiscal 2020 were from repeat customers.

If you drill down into the customers by account size rather than business size, Nutanix has 990 customers with lifetime bookings of greater than $1 million. Of these, 704 have spent between $1 million and $3 million, 143 have spent between $3 million and $5 million, 88 have spent between $5 million and $10 million, and 55 have spent more than $10 million. The growth of the overall customer base and the large customer base is absolutely linear, quarter on quarter, all the way back to 2012, where we have data.

While all of these numbers are encouraging, and the company has plenty of money in the bank, the losses at Nutanix are just immense in the past several quarters, and the employee count is growing faster than the revenue and the revenue per employee is on the decline – about half what it was two years ago, if you do the math. For a while, it looked like Nutanix was going to head into breakeven territory within a few years, but this transition to subscriptions and intense competition with VMware has really put the pressure on Nutanix to keep spending money on people to create new software and to sell what it has created more aggressively. If you add up all of the money from Q1 fiscal 2013 through Q1 fiscal 2020, Nutanix has generated $2.77 billion in revenues and just a hair over $2 billion in losses. It is a good thing that it went public to raise cash and has $899 million in the bank through October 2019 and also has $975.3 million in deferred revenue. Without that, Wall Street would have had a heart attack long since.

Scaling Out And Up With Customers

“In terms of scale, we can look at it a few different ways,” Smith elaborates, referring to data for Q1 fiscal 2020 ended in October, not the quarter that just finished and that will be reported soon. “We have nearly 300 customers who have deployed 100 nodes or more, and quite a few of those are in the several hundreds of nodes. Our largest customer is a long-time one that has over 2,000 nodes running a variety of big data and analytics applications – and no, I can’t reveal the customer – but they are taking full advantage of our webscale architecture to really drive the highest level of performance for these massive datasets.”

Among those larger Global 2000 customers, even if they have hundreds of Nutanix nodes in their environment, they typically will limit the size of a single cluster to no more than 30 nodes or 40 nodes, according to Smith, and that is to limit the blast area in the event of a cluster failure. We would have guessed that this limit was somewhere around 100 or 200 nodes, but it is apparently smaller, and probably due to the large number of applications – typically on the order of several thousand – that large enterprises tend to have. You can’t afford to have one error take out the whole shebang.

No Hyperconverged Infrastructure Is An Island

No platform can be stranded on either a particular public cloud or on premises if it hopes to succeed in this hybrid IT environment that modern enterprises have to tolerate, perhaps forever because of data sovereignty and data locality issues. And while Nutanix is positioning itself to run in the public cloud, with its Nutanix Clusters implementation of the Acropolis stack, which went into tech preview last October on bare metal instances on the Amazon Web Services public cloud and which is expected to be generally available in the first half of this year, for now disaster recovery is expected to be the primary use case for Nutanix Clusters until customers get a handle on it.

Nutanix is not foolish enough to think that it can build its own cloud – something that rival VMware once tried but that is a game for giants, and VMware has much deeper pockets than Nutanix. So forget that.

It would not be surprising to see Nutanix Clusters and the related Xi Services add-ons available on any cloud that has bare metal instances, provided there is enough demand for that cloud provider from existing Nutanix customers. Microsoft Azure is the next obvious choice for enterprise users.

The point is, Nutanix software licenses are now portable and fluid. Customers can buy subscriptions and run them on premises or in the cloud, or move them back and forth as conditions change. VMware is doing the same thing with its partnership with AWS, but VMware has a very specific set of hardware that it has created with Amazon for this purpose, not just generic bare metal instances, and so it is not necessarily going to be available in all of the AWS datacenters and regions.

The cloud effort is not just about bringing Nutanix Acropolis to a public cloud, says Smith, but also imbuing Nutanix Acropolis with the experience and services that are common on the major public clouds, including file and object storage in addition to the block storage that the Nutanix virtual SAN originally offered. That object store is native, petabyte scale, and compliant with the AWS S3 APIs like so many object stores are – and have to be. The Nutanix file system is exposed as either NFS or SMB. The Nutanix Objects overlay on the Nutanix distributed storage fabric has just started shipping late last summer, and Nutanix Files is a little bit older and already had 1,700 customers as of last fall.

The idea here is one that we have been saying all along: enterprises want to have the same substrate for compute, storage, and networking on premises and in the cloud, to the greatest extent possible, so they can avoid vendor lock in. And they don’t want to dumb it down. This is why VMware and Nutanix gave up and just did deals with AWS for cloudy infrastructure, and it is also why Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have all created private versions of their public cloud infrastructure (to varying degrees) with Outposts, Anthos, and Azure Stack, respectively.

Which brings us to containers. Nutanix was designed five years before Google open sourced the Kubernetes container orchestrator that was inspired by its famous internal Borg container management system, and there is little doubt that for new, cloud native applications, microservices are going to be put into containers – lots of them, at very fine-grained resolution – and podded up and controlled by Kubernetes. And as it did with virtual machines and virtual SANs, Nutanix is going to embed Kubernetes into its platform and make it as easy to use as possible.

“Kubernetes is the poster child for very complex technology,” says Greg Muscarella, vice president of cloud native products at Nutanix. “Getting a production-ready cluster up and running is very difficult these days. And it is even more difficult to do without Kubernetes ninjas, who are very expensive and difficult to find, especially if you are not here in Silicon Valley.”

Nutanix has a bunch of customers running its Karbon implementation of Kubernetes right now, and the clusters tend to be segmented off from the raw Acropolis virtualized machines, with maybe 15 or 20 worker nodes and a few etcd servers and a few master servers for managing Kubernetes. Development nodes are about a third that size. “There is a lot of tire kicking out there right now,” says Muscarella, adding that Nutanix expects for customers to use a mix of VMs and containers for a long, long time. In general, Muscarella adds, VMs will be used for legacy workloads and containers for new, cloud native applications, and because applications in the enterprise stick around for a long time, even with the popularity of Kubernetes right now and new applications coming into the datacenter that are deployed using it, five years from now Muscarella says that probably somewhere between 15 percent and 20 percent of applications running on Acropolis will be in containers instead of VMs.

The good news for Acropolis customers is that Nutanix is tossing in Karbon for free, and they can turn it on any time they feel like it without paying a penny for it. This will probably not be the case with VMware’s “Project Pacific,” which sounds like it will be distinct from the ESXi and vCenter virtualization stack and, very likely will not be free. But that could change, depending on how successful Nutanix is on catching the Kubernetes wave breaking down the doors into the enterprise glass house.

Be the first to comment