If FPGAs are going to take off in the datacenter in their own right, they are going to need their own killer apps. Plural. At The Next FPGA Platform event that we hosted recently in San Jose, there was plenty of talk about how FPGAs have been embedded in all kinds of devices for decades, and there is promise that they will be able to deliver better results for machine learning inference workloads than either CPUs or GPUs. But we wanted to examine two other areas where FPGAs might shine: SmartNICs and computational storage.

You might think of SmartNICs as a kind of computational storage as well as computational networking inasmuch as the processing that might ordinarily be consumed on CPUs to host virtual networking or virtual storage is offloaded to the network interface card on a compute engine dedicated to and tuned for this task. Computational storage, proper, means literally putting some form of compute acceleration in the storage device itself, preventing a load from ever getting to the CPUs in the servers that comprise a system in the first place.

To discuss the possibilities of FPGAs as engines in SmartNICs and computational storage systems, we assembled a team of panelists who know a bunch about this. Jim Dworkin, senior director of business development at Intel, and Donna Yasay, vice president of data center product marketing at Xilinx, represented the two largest suppliers of FPGAs in the market today and spoke to the SmartNIC potential, and Roger Bertschmann, chief executive officer at Eideticom, and Scott Shadley, vice president of marketing at NGD Systems, represented the computational storage vendors who have used FPGAs.

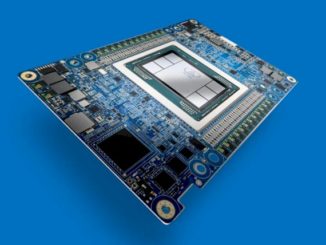

Many of the earliest uses of the FPGA in the datacenter were, of course, a rudimentary kind of SmartNIC, with the FPGA on the bump in the wire between the network and the server on the interface card, and it was usually doing a bunch of preprocessing that had to be done at extremely low latency to be done at line rate on the network and therefore not slow down processing; think high frequency trading as an example.

Without being specific about who the customer was, Yasay explains that she had done one of the first large deployments of SmartNICs in the world, and in this case the compute engine on the network interface card was based on CPUs, not FPGAs. “From that journey, what you run into, from an FPGA standpoint, you have the availability and the flexibility similar to the CPU, but you don’t have the limitation of the CPU. You actually now have exponential workloads you can deploy, and when I was just on the CPU with the SmartNIC, there was a finite limitation on workload,” Yasay says. “Personally, I think the FPGA is a panacea because you don’t have that limitation, and you have the flexibility similar to a CPU and an SoC, and you now have high performance I/O and bandwidth that can scale.”

Dworkin reminded everyone that a seven digit installation of SmartNICs based on FPGAs – and the number did not start with a zero – at Microsoft as part of its multi-generational “Catapult” project legitimized the idea of the FPGA-based SmartNIC as well as the use of FPGAs at scale in datacenters in the first place. The other thing that legitimized SmartNICs specifically was the acquisition of Arm chip maker Annapurna Labs by Amazon Web Services to create the “Nitro” family of SmartNICs, which are based on Arm cores and which are the foundation of the development of true Arm server chips, called Graviton, by AWS for deployment in its compute cloud.

“These are two different ways of solving – let’s just say similar, not completely the same – problems, and that has created a herd mentality,” says Dworkin. “It took Microsoft years to get to where they are, and a relatively shorter time for Amazon to get to where they are, and they have upped the ante a little bit with showing their Aqua use case for Redshift, a first party workload.”

And now, Dworkin adds, all of the hyperscalers and cloud builders are looking to do something similar, with Alibaba sporting a second-generation custom SoC called X-Dragon II and the others being quiet but no doubt looking to get the same advantages that SmartNICs give to AWS and Azure. (Google has a different approach, of course, that does not involve SmartNICs, but that could change.) All of the lower tier cloud and service providers are looking at SmartNICs, says Dworkin, so they can compete. “It has created an arms race that you feel when you are out there.”

Interestingly, Dworkin says that the competition among the hyperscalers and the cloud builders to add new features in the datacenter every year is playing into the hands of the FPGA makers because it is far easier and less costly to implement some features on reconfigurable compute engines than to have a new ASIC every year. Amazon and Alibaba are the exceptions for now, but it is debatable if this is the right approach, particularly for SmartNICs but also if radically different kinds of acceleration will be going on inside a server across its three or four year lifecycle in the datacenter. The reconfigurability and precise algorithmic programming of the FPGA could, he adds, make the FPGA quite a bit more sticky in the datacenter than even a CPU approach – Microsoft being the prime example of this. What started out as network virtualization and acceleration with Catapult ended up in Bing search acceleration and then BrainWave machine learning inference acceleration.

The lines between SmartNICs and computational storage are still a bit blurry, in fact, according to Bertschmann, whose company is putting FPGAs into NVM-Express flash drives to accelerate data analytics, machine learning, storage, and databases at the storage device level.

“There is going to be a push and a pull between where to do certain kinds of computations,” says Bertschmann. “I don’t think it is really clear what is going to make sense in the SmartNIC and what makes sense in the SSD in a computational storage drive.”

In the meantime, having this adjunct compute available at both ends of the storage wire is probably a benefit, particularly if it means having more modest storage cluster controllers and freeing up very expensive CPU cores within the server.

It is a no brainer that moving encryption, compression, and other algorithms down into the storage has big benefits, as Shadley points out, but not just because of the proximity of the compute and the data, but to take advantage of the parallelism inherent in storage (it is made up of drives or cards, after all) and to also leverage disaggregated compute across all of these devices. The interesting thing about NGD Systems, which has been around for six years now, has shifted from FPGAs to ASICs for those compute engines on the storage. We are always talking about the on ramp from CPUs to FPGAs but we sometimes forget that there is an off ramp from FPGAs to ASICs.

“We launched two separate platforms based on FPGAs, and they were great for PoCs and we still have customers that are deploying these solutions today,” explains Shadley. “But when it comes to traditional storage products, where the consumers are outside of Microsoft and the other hyperscalers, you like to have something that is on the form factor, the cost structure, and the ease of buying of an ASIC solution. So we moved to a CPU-enabled SSD that is driven by an ASIC device. We fully back the FPGA development, and we were able to get silicon out because of the FPGA, which we were able to hone and practice on and we are using those for the new interfaces, like CXL, that are coming out.”

It’s interesting to note that Microsoft execs set the bar for acceptance at a reasonable level. They said “get us 2x performance at 30% more cost and we’ll greenlight the project” Many people still expect 10-100x performance increases to use FPGAs for accelerators but 2x improvement when you’re talking about millions of nodes is a substantial decrease in cost for a whole datacenter.