Perhaps, many years hence, we will call the company that, more than any other, created the enterprise computing environment Big Purple now that it has acquired the company that made open source software in the enterprise safe, sane, and affordable.

Twenty years ago next month, Red Hat went public and everything about enterprise software changed. A company with some tens of millions of dollars in revenues, providing subscription support for a commercial Linux distribution for systems within a few months had a ridiculous market capitalization in excess of $20 billion and the mad dash for open source projects to be commercialized was on.

Fast forward two decades, and Red Hat is the touchstone for how to work with upstream open source software projects related to datacenter infrastructure and to bring them downstream to harden them to be enterprise grade, package them up, and then sell support for them. Red Hat is by far and away the most successful provider of commercial support for open source code, and has moved well beyond its foundational Enterprise Linux distribution, mostly through key acquisitions including the companies behind the GNU compilers, JBoss application server, the KVM hypervisor, the Gluster parallel file system, the Ceph object storage, the innovative CoreOS Linux distribution, and the Ansible software provisioning tools as well as the OpenShift container controller (a mix of in-house and Kubernetes code these days), the OpenStack cloud controller, and the CloudForms hybrid cloud management system (also largely done in-house). Red Hat, we think, still needs to have a heavy duty open source database management system distribution – perhaps several different ones with different architectural tenets – but it was also perhaps prescient in that it stayed out of the Hadoop storage and data analytics racket, which has not panned out as planned.

It is not really much of a surprise that IBM was willing to pay $34 billion to acquire Red Hat, vastly expanding its already large presence in the open source software movement. The deal, announced last October, closed last week, just after Red Hat reported its financial results for its first quarter of fiscal 2020 ended in May and just before Big Blue reported its financial results for its second quarter ended in June. Now, with the deal done, it seems appropriate to see how IBM will impact Red Hat and vice versa.

First of all, IBM’s acquisition of Red Hat is a tacit admission that the days of perpetual licensing of code in any form – something that Big Blue has mastered on its proprietary System z mainframes and Power Systems running its IBM i platform as well as on its Power Systems machines running the AIX variant of Unix – are fading fast. While IBM will be reaping profits from its proprietary systems bases for many years to come, as it has been doing for more than five decades now, it is clear that for any new application development at enterprises, Linux is the platform of choice and represents the majority of new systems being installed today. Linux is the only operating system platform that is growing, and that means all of the other ones are flat or shrinking. And by the way, they are all – even Microsoft’s Windows Server – shrinking relative to the vast explosion in server installations in the past several years. While Windows Server will have a vast installed base of tens of millions of users for many, many years to come, Linux won. And Red Hat, its formerly independent CentOS cheapie support variant, and the homegrown Linux distributions of the hyperscalers and cloud builders have made this happen despite the familiarity that Windows Server brought to the enterprise.

Open source code and subscription pricing are now expected for new stuff, even if the old ways will persist for legacy stuff. And IBM is smart enough to know this, and to also maintain is vast base of legacy transaction processing, integration, security, database, and application development tools to keep its software businesses on System z, IBM i, and AIX humming along with the still very, very impressive 85 percent gross margins that they command. You can bet that the cost of this legacy software will continue to creep up even as IBM pushes the Red Hat stack very hard into its tens of thousands of large enterprise accounts worldwide. Some companies will balk at the higher prices of that legacy software – price increases IBM was going to have to do because the cost of software development and support scales with the cost of people and does not scale down with Moore’s Law – and now, after Big Blue has bought Red Hat, it will be there to steer them into a cheaper, open, and arguably more modern option. At the same time, IBM will continue to push the Linux stack on its System z and Power platforms and will continue to add open source code into its proprietary operating systems to give customers a reason to stay and pay.

In a conference call last week after the deal closed, Arvind Krishna, senior vice president in charge of IBM’s cloud and cognitive software products, and Paul Cormier, president of Red Hat’s products and technologies, said repeatedly that Big Blue would absolutely be taking a hands-off approach its new commercial open source software operation.

Here is how Cormier explained it: “The problem we had back in the Unix days, and to a certain extent in the Linux days as well, was companies going with these siloed approaches. I think we both recognize that won’t work here and that won’t scale the technology. That independence is essential to assure our partners – who may be competitors to IBM – that they have an equal shot at the business out there.”

To that end, Krishna made it clear that Red Hat would keep its own independent sales force and that this sales force would not be compensated in any fashion to sell IBM’s own software stack; that Red Hat would participate in the open source projects it sought fit to do so and maintain its own roadmaps and commercialization plans; and that Red Hat will be keeping its own brands, facilities, employees, and partner programs with hardware and software companies. IBM cannot in any way alienate the vast base of partners who push the vast majority of Enterprise Linux and stuff further up the Red Hat stack.

What IBM can do, and will do, is promote the Red Hat stack on its own platforms like crazy and ensure that Red Hat maintains its neutral Switzerland status with those who provide other platforms. It can also provide the funding for Red hat to do other key acquisitions or to invest in commercializing other important open source projects where the Red Hat stack has some holes still. Databases and datastores are the obvious ones, but there are plenty that Big Purple could get behind and push; file systems are another area where there are some needs. CockroachDB is an interesting option for a cross-cloud, distributed SQL database that would also play well across Big Blue’s own several dozen global datacenters in the IBM Cloud; there are many other database providers doing innovative things. Any one of the NVM-Express storage startups – Excelero, Vast Data, and Lightbits Labs come immediately to mind – would be a welcome addition to the infrastructure stack, too. IBM could even go crazy and open source its Db2 database and its Spectrum Scale (formerly GPFS) parallel file system with some nudging from Red Hat.

So, IBM is not going to mess with Red Hat, and Red Hat’s Enterprise Linux and OpenShift will be the preferred platforms that IBM pushes on its own systems and, by virtue of Red Hat’s partners, those of others. We do not see SUSE Linux or another software platform provider suddenly eating market share away from Red Hat, which has tens of thousands of customers and around 4 million servers running its wares (around 10 percent of the installed base of iron). There is probably twice that number of machines that are running at the hyperscalers and cloud builders on their homegrown Linux distributions, and another percent or so using another Linux distribution, and the remainder are self-supported Linuxes running at telcos, service providers, and other enterprises. (These are our rough guesses.)

Red Hat will have an increasingly large impact on IBM as this open source support business continues to grow and as the rest of Big Blue continues to decline or grow only modestly. IBM’s financial model for decades was to grow revenues in the single digits and to boost earning per share in the double digits, but Red Hat has been growing at 20 percent or so, quarter after quarter, like clockwork, that for it to slow down seems almost inconceivable. In fact, Red Hat got a slight bump in the most recent two quarters after the Red Hat acquisition by IBM was announced, according to Krishna, which bodes well for the combination of the two companies.

To try to figure out that impact, let’s take a look at the numbers. We will start with IBM and then Red Hat and look at what would have happened if this deal had already been done five years ago.

In the second quarter, IBM booked $19.16 billion in sales, down 4.2 percent, but was able to boost net income by 3.9 percent to $2.5 billion. IBM has done some reclassifications of cloud and integration software products starting this year, which makes comparisons with long term data since it last recategorized its financials in 2014 difficult, but we can still get a pretty good read on the core systems business that we like to keep track of.

In the quarter ended in June, IBM sold $1.75 billion in systems, which includes servers and storage but not storage management software or file systems, the latter of which is sold separately and within a different division of IBM. (We actually don’t know which one.) IBM’s Systems group sold another $171 million in stuff to other divisions for hosting and such, bringing the total to $1.92 billion. IBM does not provide revenues for particular lines, but did say that System z sales were off a stunning 42 percent as the z14 processor cycle is losing steam, but that Power Systems sales rose by 1 percent; storage sales fell by 22 percent.

We estimate that IBM’s systems hardware (against both servers and storage) accounted for $1.35 billion, falling 24.5 percent and operating systems another $394 million, up 1.5 percent. (IBM talks in constant currency, but we want to know as reported and do our best to estimate what this is each quarter for each of IBM’s product lines.) Big Blue had gross profits of $921 million on its systems and operating systems, but after all costs were allocated to it, the Systems group only had $61 million in pre-tax income. We suspect that the Power10 ramp is adding into its costs.

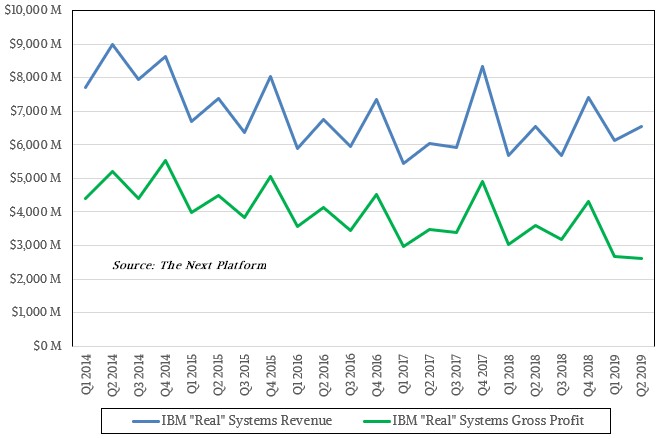

This is not, of course, an adequate representation of IBM’s systems business, something that is lost on many people but not us. IBM sells a slew of transaction processing, middleware, and other software, as well as technical support and financial services, to its own customers using System z and Power Systems machinery as well as to those using other hardware platforms. Every quarter we try to reckon what this real systems business might look like. Here is the trend after adding in Q2 2019:

Our best guess is that IBM’s overall “real” systems business – meaning sales of its own iron running its own software and using its own services and not counting software and services for use with other platforms – was flat at $6.56 billion in the quarter, which is pretty good considering the massive decline in mainframe sales. However, thanks to that mainframe dropoff, gross profits for this indigenous systems business dropped by 27 percent to $2.62 billion, we think.

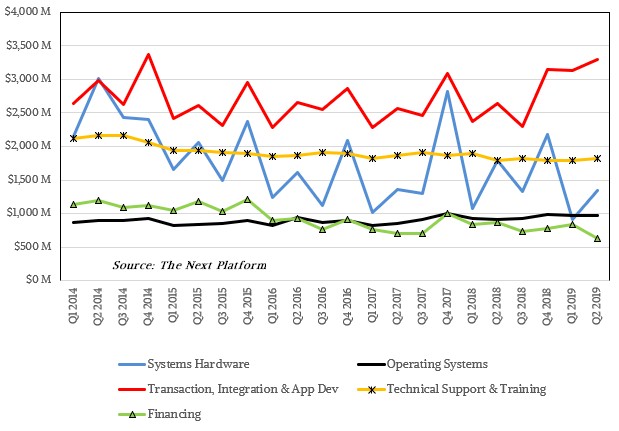

This dicing and slicing of IBM’s business has been useful over the past five years in reminding people that the company had a very large and profitable systems business (not counting databases) despite the way it presents its financials. But it is not going to be as useful in the Red Hat era because Red Hat mostly sells iron for non-IBM equipment. So we went back and tallied up all of the numbers for Red Hat since early 2014, split by infrastructure software and application development and management divisions, and added them together to create an amalgam of IBM and Red Hat as if they hard merged back in January 2014. Red Hat’s fiscal quarters end a month earlier than IBM’s calendar quarters, so the superposition of the two sets of numbers is a little blurry, but it gives us an idea of how IBM’s new and improved “real” systems business, including all that stuff on competitor’s iron that we excluded before, will combine. Take a look:

That black line shows that Red Hat does a lot to stabilize IBM’s operating system revenues, which will be hovering at around $1 billion a quarter as the two companies merge. Now, operating systems is almost as large as systems hardware sales, which to our eye is averaging somewhere around $1.5 billion per quarter at IBM, even after the mainframe slowdown as the market consumes z14 capacity and awaits the z15 rollout next year. IBM Global Finance is averaging just under $1 billion per quarter and technical support and training of the two companies combined is just a tad under $2 billion a quarter.

Look at what happens when you add in Red Hat’s application development and management tools to IBM’s transaction processing, integration, and management tools, and expand out to all platforms that IBM and Red Hat sell onto, not just IBM’s machinery. This systems software – which again does not include databases – is growing and consistently larger over the past five years than the declining hardware business at big Blue, which has suffered from the sale of the System x X86 server business to Lenovo.

If you add Red Hat into IBM, then the first quarter would have seen a slightly smaller decline in sales and a slightly higher bump in net income, but nothing big. The “real” systems business – and the broader one, not just the indigenous one we have always talked about before – would have grown by about 1 percent to $8.07 billion. In the trailing twelve months, this combined IBM and Red Hat systems business brought in $31.7 billion. Hewlett Packard Enterprise and Dell might sell more server hardware, but they do not have a complete stack, and in fact, they need IBM to complete their stacks. Which is funny, if you think about it.

As the Red Hat business continues to grow – let’s assume IBM can push it up to 25 percent per quarter – then by the end of 2023, it will be running at $2.5 billion per quarter, about 2.5X that of its current run rate. If Big Blue could push that up to 30 percent growth, then it will be at $3.3 billion per quarter as it exits 2023, or about 10 percent higher than the current annual revenue of the Red Hat business. At that rate of revenue generation, IBM will get the $34 billion back in aggregate revenue from now until the end of 2023 that it paid to acquire Red Hat in the first place.

The Red Hat revenue stream might be enough to keep IBM’s overall revenue from slipping only moderately over that time, and it might just be enough to fill in the likely gap as legacy systems continue their slow decline. It will be interesting to see what IBM does next to try to actually get growth. Expect a lot of noise about the Red Hat stack on the IBM Cloud, and hopefully on Power Systems iron.

Crazy days ahead

IBM Systems are no more “prepriatary” than Micorosoft, Oracle or Apple. In fact the i and z systems are some of the most “open” Operating Systems available.

IBM systems have always provided speed, stability and first class support. That’s something that Microsoft and Apple have never provided. I only allow Microsoft servers in my company’s data center if an application requires it, as it’s TCO is much higher than most any other platform.