The demand for compute is so strong among the hyperscalers and cloud builders that nothing seems to be slowing down Intel’s datacenter business. Not delays in processor rollouts due to the difficulties in ramping 14 nanometer and 10 nanometer processes as the pace of Moore’s Law increases in transistor density and the lowering of the cost of chips slows. Not what is a pretty substantial price increase that accompanies the core scale out and feature expansion in the “Skylake” Xeon SP processors. Not the credible competition from IBM, AMD, Cavium, and Qualcomm.

The sun is shining on the datacenter, and Intel, now the world’s second largest chip maker behind Samsung thanks to the huge spike in memory prices, is making hay like crazy. At the same time, the top brass at the company are warning Wall Street that the transition to 10 nanometer technologies is taking longer than expected and will not yield in quite the same manner as Intel had hoped and that it will be taking a less aggressive stance on the move to 7 nanometer chip making processes.

The market for compute is expanding so fast, thanks to the expected and immense demand of the hyperscalers and cloud builders as well as a rebound in spending in the past six months by enterprises, that there is plenty of money to go around. Which is why AMD is also doing well in the datacenter and has not adversely impacted Intel. Yet. When the money gets tight in the enterprise, or hyperscalers and cloud builders tighten the negotiating screws, there will be a different story. But not today.

In the first quarter ended in March, Intel posted sales of $16.1 billion, up 8.6 percent and beating its own expectations by a sizeable margin. Lots of tech companies are seeing something of a revenue bump because revenue recognition rules just changed, and Intel is one of them, but the underlying strength of the business – particularly that of its Data Center Group and adjacent flash and FPGA lines – helped the company bring $4.45 billion to the bottom line, an increase of 50.7 percent and representing 27.7 percent of revenues. That is software-class profits for a manufacturer of very complex products, quite a feat indeed. It doesn’t hurt that Intel virtually has a monopoly on volume manufacturing of processors in the datacenter, to be sure, and it is safe to say that a very big portion of the revenue jump is due to the premium it is charging for Skylake Xeons. The price of anything is that which the market will bear, and right now, CPUs, GPUs, DRAM, and flash are all in high demand and therefore their prices are higher than anyone would have expected two years ago.

You can begin to see why Intel wants to keep chips at mature, well-yielding, and not costly 14 nanometer processes for as long as possible and not take the full hit of moving all Core client and all Xeon server processors to 10 nanometer techniques, where the transistor performance is good but the yields are not what Intel expected due to the complexity of the manufacturing process. This is a cost can that Intel is happy to kick down the road. Again, in fact.

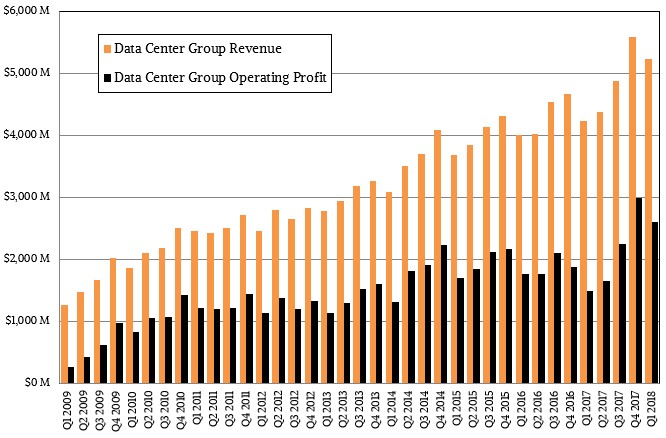

The Data Center Group is the engine that drives Intel, and it was humming on all cylinders in the first quarter as it had been in the final quarter of 2017, when the server and storage and networking markets all set new peaks. A few years back, Intel had projected that Datacenter Group could grow at 15 percent per year for the foreseeable future, and it fell short of those targets as enterprise spending slowed soon after it made those pronouncements. This is an object lesson in something that is very important in the Age of Machine Learning: Many things cannot be predicted, and the only way to know for sure is to live through it. Business managers make their best guesses about the future, and so do we, and then we act in concert to see what will be the truth. We love prognostication, perhaps because we have over-active frontal lobes, and it is fun to see how close to that truth we can come.

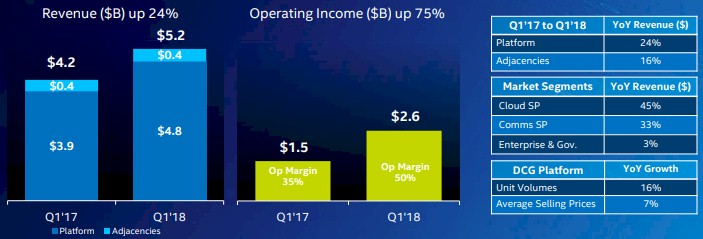

In the quarter, Data Center Group posted $4.82 billion in platform sales, which includes Xeon and Xeon Phi processors, chipsets, and motherboards, up 24.4 percent, which four times faster growth than Intel had overall. Data Center Group had another $410 million in sales of “adjacency” products, which includes Ethernet adapter cards, Omni-Path network switches and adapters, early silicon photonics, and such, up 16.2 percent from the year ago period. Overall, Data Center Group posted revenues of $5.23 billion, an increase of 23.7 percent year on year. Now comes the fun bit.

Data Center Group had an operating profit of $2.6 billion, up a stunning 75 percent. Part of that is the 10 nanometer push out, part of that is the Skylake premium, and part of it is increasing average selling prices as some customers move up the stack, and some of it is sheer volume of processors and system boards. Hold on for the fun bit. Intel sold $7.62 billion in Core and Atom client processors, up a mere 3 percent, with another $605 million in adjacencies (chipsets and motherboards again), up 4.5 percent. But operating profits for the Client Computing Group fell by 7.9 percent to $2.79 billion against total sales of $8.22 billion, up 3.1 percent. Ok, there are two fun bits. First, you can see the economic cost of that 10 nanometer ramp, which is already affecting the Xeon line because it has to share some of the development and manufacturing ramp costs. And second, Data Center Group is for the first time almost throwing off as much gross profits as the much larger Client Computing Group, which has a 57 percent larger revenue stream. This may be a temporary condition set by the booming server market and the state of manufacturing processes at Intel, or it may be The Way Things Are Now. We think it is the former, not the latter, but as AMD gets more aggressive on the desktop, this could hurt Intel’s profits there, even if it does put out Core chips with integrated AMD “Vega” GPUs on them.

To our eyes, the revenue in the first quarter of 2017 was a little light, based on the trends in the chart above, and the profits were even a little lighter, so the compares to the first quarter of 2018 were therefore a little easier. Just a little.

Here is how Intel thinks about it:

The operating margins for Data Center Group are back up in the 50 percent range that Intel likes to hold it at, and they were trending a lot lower than that in the first half of 2017 as the “Broadwell” Xeon E5s were waning and the market was awaiting the Skylake Xeon SPs. The important things to note here is that sales to cloud service providers (what we call hyperscalers and cloud builders) rose by 45 percent and sales to communications service providers rose by 33 percent. Brian Krzanich, Intel’s chief executive officer, said on a conference call with Wall Street analysts that together, these sets of customers comprised over 60 percent of the revenues for Data Center Group. Sales of chippery and mobos to enterprise customers rose, somewhat unexpectedly, by 3 percent in the first quarter, but Krzanich said that Intel’s forecasts are for spending to go negative to the tune of a few points each quarter over the long term. Not just because customers are moving workloads to the cloud or using services created by the hyperscalers, but (we think) because they are getting better at squeezing more work out of the iron they have.

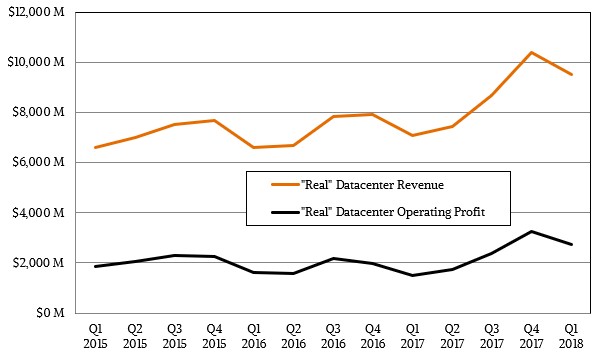

Data Center Group is not the only division that sells products aimed at the glass house. There are adjacent markets that are growing and helping boost its real datacenter business. They include the IoT Group (a hodgepodge of stuff aimed at the edge and endpoints), the Non-Volatile Storage Group (flash and 3D XPoint memory), and the Programmable Solutions Group (Altera FPGAs). Here is how they did, as reported:

It is hard to imagine that, given the intense demand for flash and the high prices that makers are commanding that Intel’s Non-Volatile Solutions Group is still not profitable, but it is heading towards breakeven. In the first quarter, this group had $1.04 billion in sales and posted an operating loss of $81 million. The FPGA business did well, with sales up 17 percent to $498 million, but operating profits were essentially flat at $97 million, so there is pressure here even as the datacenter part of this business more than doubled and sales of the most advanced FPGAs (based on 14 nanometer, 20 nanometer, and 28 nanometer processes) rose by more than 40 percent. This would suggest that the embedded part of the Altera FPGA business is under price as well as competitive pressure.

This is not the “real” datacenter business at Intel, but we can sort of back into it. To do so, we take the actual Data Center Group sales and add to it half of the IoT Group and 75 percent of the FPGA and non-volatile storage revenues. We then figure out its operating profit by applying the same percentages to the operating incomes of these groups. Here is what that looks like since Intel reclassified its financial results in 2015:

By our rough reckoning, Intel’s real datacenter business posted sales of $6.81 billion, up 22.4 percent, and its operating profit hit $2.73 billion, up 80.4 percent and comprising 40.1 percent of that revenue. That is lower operating margins, because the IoT and non-volatile flash businesses are not yet as profitable as the core Xeon chip business. Their profits may rise just as intense competition comes to compute later this year and impacts the Xeon business. Or there may be such a dearth of supply for compute that everybody gets a breather, as happened with DRAM and flash and which made all the memory makers very rich in the past 18 months.

That brings us all the way back to the 10 nanometer ramp and the anticipated move to 7 nanometer manufacturing. Krzanich said that Intel was shipping 10 nanometer products in low volume, but added that the future “Whiskey Lake” Cores and “Cascade Lake” Xeons would be etched with an enhanced 14 nanometer process, what we would call 14++ nanometer using the latest Intel lingo. This will be the fourth generation of server chips to use a 14 nanometer process, with the Broadwells being the first, the Skylakes were the second, the “Kaby Lake” Xeon E3s launched last April were the third and very short generation with no Xeon SP variants, and the Cascade Lakes will be the fourth.

The 10 nanometer jump has been problematic from the beginning, and Intel was admittedly aggressive in its timing and the level of performance and shrinkage it pushed for, and Krzanich said as much. “We are shipping in low volume and yields are improving, but the rate of improvement is slower than we anticipated,” Krzanich explained. “As a result, volume production is moving from the second half of 2018 into 2019. We understand the yield issues and have defined improvements for them, but they will take time to implement and qualify.”

The issue is not the tooling or the basic transistors, but the number of masking steps that are needed to build up the circuits using immersion lithography. It is the high number of steps, where everything has to align precisely at nanoscale, that is causing the yield issues. That is driving up the cost of each process leap and also increasing the time it takes to make those leaps. But the combination of architectural tweaks and process refinements have boosted the performance of cores by 70 percent over the span from Broadwell to Skylake, and that is how Intel will be engineering going forward. The good news is that a lot of the equipment and experience that is being developed for 10 nanometer immersion lithography will be applicable to 7 nanometer extreme ultraviolet lithography, these being the last and the first generations of these techniques at Intel. In the meantime, full production of 10 nanometer chips is being pushed out from the second half of 2018 into 2019 as Intel works up the yield curve. So the Core and Xeon roadmaps just all changed.

Intel also expects for headwinds in the Data Center Group. “We have data centric growth going from the middle teens to higher teens,” Robert Swan, Intel’s chief financial officer, said on the call, referring to the “data centric businesses” that include DCG, ISG, NSG, and PSG to use Intel’s abbreviations for the groups that have any play in the datacenter. “You can attribute virtually all of that to Data Center Group because obviously it is the biggest component. But we do expect there to be deceleration for DCG growth from first half to second half, for sure. We hope we are wrong, but where we sit right now, we see the trends continuing into Q2. But we will have tougher comps. We will have tougher competition going into the second half, too. And we are going to wait until July to see how we see the trends we have experienced through the first four months of the year play out to say anything about the second half.”

Be the first to comment