Supercomputing, by definition, is an esoteric, exotic, and relatively small slice of the overall IT landscape, but it is, also by definition, a vital driver of innovation within IT and in all of the segments of the market where simulation, modeling, and now machine learning are used to provide goods and services.

As we have pointed out many times, the supercomputing business is not, however, one that is easy to participate in and generate a regular stream of revenues and predictable profits and it is most certainly one where the vendors and their customers have to, by necessity, take the long view. This is what it means to be on the bleeding edge. Only certain academic, government, and corporate organizations can indulge in supercomputing, and even though the HPC sector is larger than supercomputing, the same limitations on applicability hold. This has frustrated the HPC community to no end, in that we all know that much good could come from deploying HPC approaches to all kinds of businesses, and it could have created an HPC bubble if all manufacturers alone had adopted these technologies instead of a relative handful. (This is the so-called “missing middle” of HPC users in manufacturing.)

It is with all of this in mind that we ponder the financial results of supercomputer maker Cray, which posted numbers for its second quarter of 2017 this week and which, we think, has some implications for the HPC sector and its new and rapidly evolving adjacencies in machine learning and data analytics. It could be that HPC is saved by machine learning, but is no longer in the driver’s seat when it comes to system architecture. And companies like Cray, which have deep experience in simulation and modeling, have spent years trying to reposition their products and companies to intersect this opportunity. Thus far, there has not been much of a bump thanks to machine learning, but there are, as Cray’s top brass explained in a conference call with Wall Street analysts, some optimistic signs for both this segment and for data analytics in general.

In the quarter ended in June, Cray did better than its most recent forecasts, with revenues of $87.1 million, which was $27 million higher than expected but still 13.1 percent lower than the $100.2 million the company booked in the year-ago period. The bump in revenue was driven by the acceptance of a major machine that came in a quarter earlier than expected. But Cray chief financial officer Brian Henry said on the call that this machine, which was unnamed, was up against some stiff competition and was priced very aggressively while at the same time component costs were higher and therefore the gross margins on the deal were lower than the typical Cray deal. This was part of the reason why Cray booked a $6.8 million loss in the quarter, a loss that was about a third of the one it booked in its first quarter of 2017.

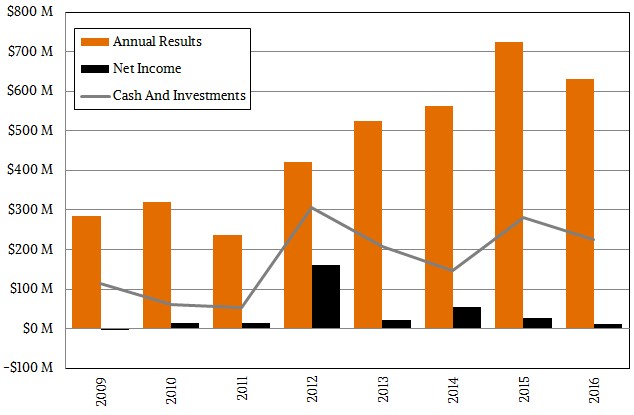

In recent years, thanks in part to HPC budgets and in the rhythm of new compute and networking technologies, Cray’s revenues have bunched up in the third and fourth quarter of the year, and in 2016, as we previously reported, Cray booked a record $346.6 million in revenues with a $51.8 million profit in the fourth quarter. It will probably be a while before Cray sees a quarter like that again, but to reach its long-term goal of breaking through $1 billion in sales, it will have to have fourth quarters like that again.

Product sales have been pretty light so far in 2017, with $21.1 million of new clusters or storage sold in the first quarter and $51.5 million in iron sold in the second quarter. The good news, according to Peter Ungaro, the company’s chief executive officer, is that the pipeline for Cray’s systems is growing and was up slightly in the second quarter.

The pipeline of opportunities that Cray has with commercial customers, as distinct from academic and government HPC centers, is growing faster than the pipeline in those traditional areas. The problem, it seems, is that while the pipelines are wider, the deals are coming slower, so the throughput of deals, as measured by booked revenues, may not be higher. More customers is always better, of course, because it is a safer way to have consistent sales, but if the supercomputer market illustrates anything, it is the difficulty of getting consistent results from a capricious market that is dependent on government and academic funding.

Cray is not providing any guidance for 2018 because visibility in the future is just too dim given the current political and economic climates, but Henry said that Cray expects sales of $60 million or so in the third quarter and that for the full year, the company would come in at the low end of its previous guidance. In the conference call for the first quarter ended in March, Cray said to expect sales of between $400 million and $450 million, and now it is projecting a straight $400 million, which means that it expects to bring in around $194 million in the fourth quarter of this year. That is the company’s smallest fourth quarter since 2012, and that annual revenue level for 2017 will be lower than that attained in 2012.

We have said many times that Cray has to be analyzed on an annual basis, and as you can see from the charts above, thanks to selling off its “Gemini” and “Aries” interconnect businesses to Intel back in 2012, Cray had record profits against $421 million in sales; about three-quarters of the $161 million in net income the company posted back then was from that interconnect deal with Intel. It looks like about $50 million in deals that were expected for acceptance in 2017 have shifted out to 2018.

There is chatter on Wall Street that Cray could do somewhere around $600 million in sales in 2018 and then maybe $700 million in sales in 2019, but Cray was mum on these figures. “I have conservative expectations and high hopes about what may happen over the next couple of years,” Ungaro said when prompted to comment on such figures. These results would be a mirror image of sorts of the decline that Cray saw since posting record sales of $725 million in 2015, which slid further to $630 million in 2016. Cray’s profits have also slid over this time, a reflection of increasing component costs and intense competition among traditional HPC players and incursions by upstarts that are coming in from the hyperscale space.

This slowdown in supercomputer sales has taken Cray a bit by surprise, particularly because its tight alliance with Intel was supposed to help it win more and bigger deals. But a turnaround has been hard to come by, and so Cray has decided to cut its workforce by 14 percent, or 190 of its 1,360 people. Just before announcing its financial results, Cray also said that it was buying up the ClusterStor clustered storage business from disk drive maker Seagate Technology, which got this business by virtue of its acquisition of Xyratex in December 2013 for $374 million. (The deal was worth $296 million net of Xyratex cash.) Cray did not disclose how much it was paying for the ClusterStor business, but said that it would be taking on about 100 employees, mainly in research, development, and customer and channel support, and that these employees would add about $20 million to its operational expenses. Cray added that the ClusterStor business would operate at breakeven in 2018, and that because a large portion of the $80 million to $100 million in storage it has sold in a good year was ClusterStor devices rebranded as Sonexion arrays, it would be able to increase the gross margins in its own array business thanks to the deal.

We think that Cray really wants to do a much more tighter integration of its compute and storage platforms, and by controlling the ClusterStor stack and its variant of the Lustre parallel file system, Cray can do this and do a better job fighting against IBM’s Spectrum (GPFS) parallel file system and the Lustre and GPFS products from DataDirect Networks. The point that Ungaro wanted to make is that the total addressable market for such high performance storage is somewhere between $1 billion and $2 billion and it is growing at between 10 percent and 13 percent, depending on the year, and this is a lot more growth than the HPC compute segment and the upper echelon of the supercomputer space within that HPC market.

The slowdown also seems to have something to do with a lack of excitement around Intel’s “Skylake” Xeon processors, which launched in early July. Ungaro said that Skylake hit the market just when memory and flash prices are high and the supercomputer space is seeing softness, and that the normal, early uptake bump that comes in the wake of an Intel processor launch did not happen with Skylake.

The supercomputer slowdown has a lot of vectors, we think, and the delayed Skylake launch, which was anticipated for around September 2016, and difficulties in getting “Pascal” and now “Volta” GPU accelerators from Nvidia are just part of it. And even with all of the investment in exascale systems in the coming years, Ungaro said that rather than expecting for the market to expand with a wider variety of systems, it would be more the fact that the planned machines would just get bigger rather than make any substantial shifts. So, for instance, machines that might cost $50 million to $100 million with a certain level of performance might get budgeted with $100 million to $200 million with a research and development component to bring pull in some technologies that might otherwise be commercialized later.

“The slowdown in our market has continued into 2017, especially at the high end,” explained Ungaro. “That, combined with our estimates for the rebound, and the need to continue to invest in several areas to enable further growth drove our decision to adjust our workforce. While our competitive position remains strong and our win rates have remained in excellent shape, we need to better align the cost structure of our company.”

Here was the telling thing that Ungaro said a few moments later: “This is the longest and deepest downturn that I have seen in my 25 years in the industry. But we are working to come out of it a stronger, leaner, and more nimble organization.”

This kind of belt tightening has been going on in the compute and storage sectors – it is not just something that Cray is living through – and it is because the margins are shrinking.

Be the first to comment