While Amazon Web Services has first mover advantage when it comes to building a compute and storage cloud, it would be a mistake to believe that the division of the world’s largest online retailer can rest on its laurels. AWS has to work hard every day to make its cloud cheaper and better, and that is because both Microsoft and Google are gunning for it.

And the threat is ever-present, and has been for the past several years, which is why you see the AWS share of the cloud revenue stream hovering around a third. At some price and some level of function, customers will move, and moreover, there are customers who love the Microsoft’s Windows Server platform, its development tools, and its application software and there are other customers who think Google has the smartest infrastructure on the planet and is the safest place to invest in the future of compute and storage.

No matter what your own preferences may be, what can be said for certain is that AWS, Microsoft, and Google have built the largest platforms that the Earth has ever seen and the largest platform businesses as they sell slices of it for companies to use to run their own businesses. Moreover, what we also know for sure is that the intense competition between these three cloud builders, who are also hyperscalers running applications at scale in their own right, is good for the market, push up capabilities and pushing down prices more than otherwise might be the case.

GPU compute capacity excepted, of course, as high demand is still chasing short supplies. But this will normalize at some point, fear not. This is what markets do.

Rather than look at these companies separately, as we might otherwise do, we decided to look at them at the same time as they all reported their revenues for the fourth quarter of 2023. We have been watching AWS like a hawk since founding The Next Platform nearly a decade ago, but never got around to peeling apart the financials of Microsoft and Google, which have only in recent years started talking about their cloud businesses as their revenues in this area became significant enough that they have to. We should have been doing this all along, of course. The best time to do anything is ten years ago; the second best time is right now.

With a few years of trend data in hand and the competition from Microsoft and Google coming on strong, now is actually a perfect time to compare and contrast the Big Three in cloud. So let’s get on with it.

Cloud 1: Amazon Web Services

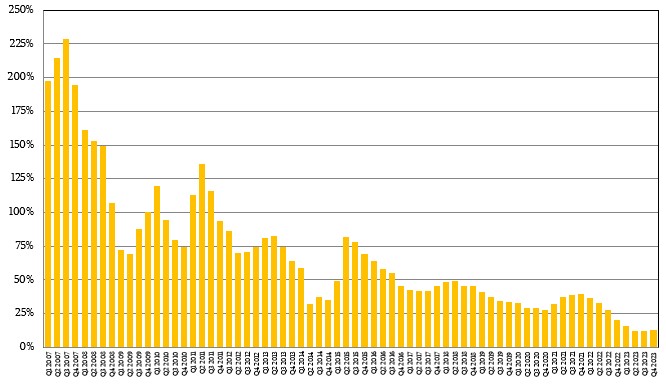

Way back in February 2019, we asked the question: When Does AWS Break Through $100 Billion? And based on a couple of different scenarios, some of which were utterly ridiculous (such as the growth rates AWS enjoyed back in 2018 continuing out into the future), we thought in the final analysis that AWS would break through $100 billion in annual sales by its 20th anniversary in 2026 and quite possibly before.

It turns out that this will happen quite a bit before that, here in 2024 in fact. And a lot of that will have to do with the surge in interest in Generative AI and the dearth of GPUs outside of the big clouds and hyperscalers.

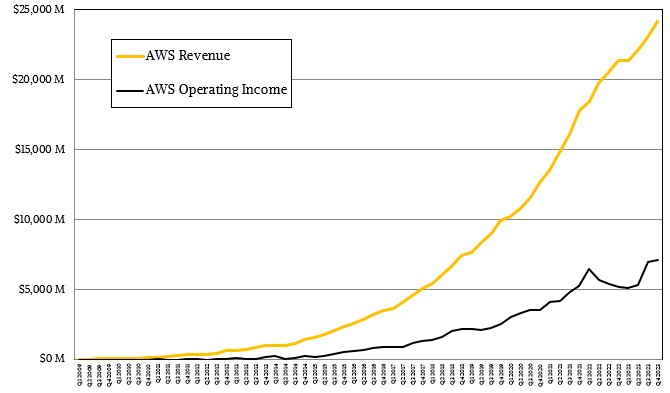

In the final quarter of 2023, AWS posted revenues of $24.2 billion, up 13.2 percent, and operating income rose by a much faster 37.7 percent to $7.17 billion, representing 29.6 percent of revenues. For the full year, AWS revenues were up by 13.3 percent, to $90.76 billion, and operating income was up a mere 7.8 percent to $24.63 billion, representing a more average 27.1 percent of revenues.

This is an amazing business that AWS has built, and it is arguably the most ornate and complex platform that anyone has assembled. And interestingly, you really can’t buy it – you can only rent it. It really only works at scale, and that is why we don’t see AWS Outposts scattered around the co-location facilities and private datacenters of the world.

While the growth of AWS is still outpacing global gross domestic product, it has been slowing in recent years as all platforms inevitably do. Otherwise, AWS would be larger than the GDP of the United States or China by now.

That 13.3 percent growth rate for AWS in 2023 was more than double than the GDP growth rate in the United States for last year, which is currently pegged at 6.3 percent, and it is considerably larger than the 3.1 percent global GDP growth rate projection for 2023. It may be hard to believe, but at some point in the next decade, AWS will only grow at a rate a little higher than GDP in the countries where it has customers. It happens to every platform until a new platform comes along. The trick for AWS – and indeed all platform providers – is to be the one building the next platform and not just white-knuckle gripping the current platform.

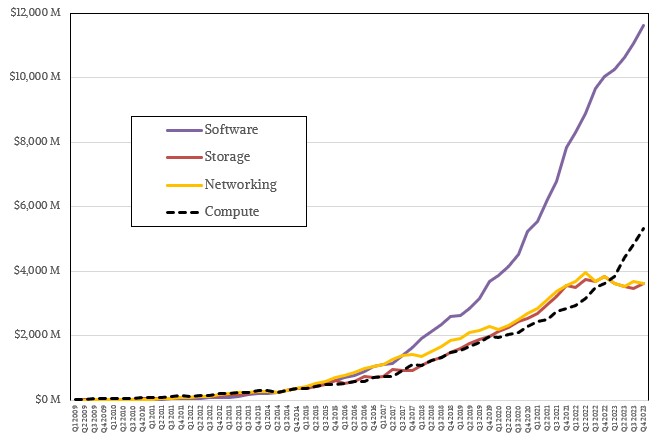

AWS does not break out its revenues by categories, but we have done some spreadsheet witchcraft to try to suss out what the revenue streams are for compute, storage, networking, and software for the world’s largest cloud builder. Here is what we think that breakout might look like:

In the early days of AWS, compute, networking, and storage accounted for the vast majority of revenues for AWS, we think, but that has shifted over time as more and more software content – either from AWS or from third parties – has been added to the AWS cloud.

We think that Compute bottomed out as a share of the AWS revenue stream in late 2020, and has been on the rise as both HPC simulation and modeling and AI training and inference have taken off on AWS. We reckon that customers have been much more careful on storage and network spending so they can spend more on compute and software – much as we see across the enterprise no matter what the platform.

If you strip out everything but the systems software – and that is hard to do, we realize – we think that the “real” datacenter business at AWS, meaning the combination of compute, storage, and networking, accounted for $12.59 billion in revenues, up 11.1 percent, and that operating income for this business came to $3.73 billion, up 35.1 percent and representing 25.2 percent of revenues. The software layer that rides above this foundational datacenter infrastructure is more profitable, but still quite expensive to develop.

Cloud 2: Microsoft Cloud, Including Azure

We said this a long time ago, and we will say it again now. Microsoft had built a massive, distributed, global platform on the PC and leveraged that to take on and take a big piece out of the corporate datacenter (until Linux came along), and unless it was completely inept at building hyperscale infrastructure, by virtue of its vast systems and application business, it had tens of millions of captive Windows Server and Windows PC customers for which it could create useful services to run from the cloud.

And that, in a nutshell, is why Microsoft could go from what looked like a confused also-ran with the initial attempts at the Azure cloud to the behemoth cloud builder and technology innovator that Microsoft is today. That is why Microsoft has already built a larger cloud business than AWS has today by many measures and a much more profitable one to boot.

Microsoft dices and slices its business in various ways as it talks about cloud and platforms. It can be tricky to try to estimate how much of this is the core, “real” Microsoft systems business, which is the number we want to compare what Microsoft is doing against all of the other platforms currently being sold or rented today and in the past. Not everything on Azure is focused on datacenter workloads – business applications, data analytics, HPC and AI training, and so forth – and not everything that the company calls “Microsoft Cloud” has to do with datacenter workloads. So this is a tricky bit of estimating.

Let’s step through this.

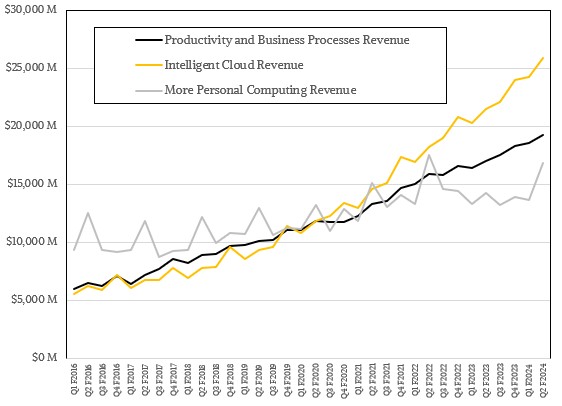

Microsoft has three different groups, and the Intelligent Cloud group is the one that is most interesting to us here at The Next Platform. This is the one that includes the Windows Server platform as well as the Azure cloud platform as well as Microsoft’s various databases and application development tools.

The other two groups – Productivity and Business Processes and then More Personal Computing – are interesting to us only inasmuch as they provide operating income that Microsoft can use to invest in its Windows Server system and Azure cloud platforms.

As you can see from the chart above, this Intelligent Cloud group has been outgrowing the company’s application business and its PC business since fiscal 2017, and became Microsoft’s largest operating group three years ago, and there is no reason to believe that its growth rate will not continue to be higher for the foreseeable future. The cost a grief of AI training and inference will support that growth until more efficient and better models and cheaper compute engines become available for GenAI and other artificial intelligence workloads.

In the quarter ended in December, which is Microsoft’s second quarter of its fiscal 2024 year, Intelligent Cloud posted sales of $25.88 billion, up 20.3 percent, and operating income rose by 39.9 percent to $12.46 billion, representing 48.1 percent of revenues. This is not as profitable as the Microsoft application software business at the operating level, but it is more profitable than the PC business.

For the full year, Intelligent Cloud had sales of $96.21 billion, up 17.9 percent, and operating income was $44.21 billion, up 26 percent and representing 46 percent of revenues.

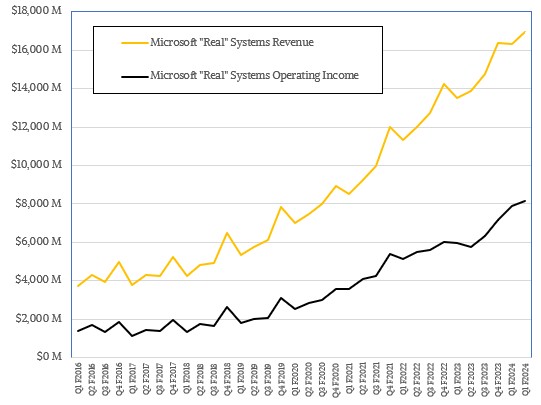

To get a sense of what Microsoft’s “real” systems business looks like, we gathered up industry data about the database and datastore and application development markets and extracted out our best guess of what Microsoft’s database and application development tools revenue streams are and subtracted those estimates from the quarterly Intelligent Cloud revenues. It looks like this:

You can see the ups and downs of the on-site Windows Server systems upgrade cycles that is superimposed on the linearly growing Azure Cloud business in this data. This data does not violate our sensibilities, but if you have some input, don’t be shy. We are trying to build a better model.

Our best guess is that in Q2 F2024, Microsoft had $16.97 billion in “real” systems sales across the Azure and on-premises Windows Server platforms, and operating income was in the range of $8.17 billion. To be honest, we are less sure how to allocate this because we don’t know how profitable the businesses we extracted out of the Intelligent Cloud group are. But around two thirds of this revenue is coming from the “real” systems at Microsoft, so it probably doesn’t change the profitability all that much.

In the trailing twelve months, this “real” systems business at Microsoft brought in $64.38 billion, up 18.5 percent, and had $29.57 billion in operating income, up 26.6 percent and representing 45.9 percent of revenues.

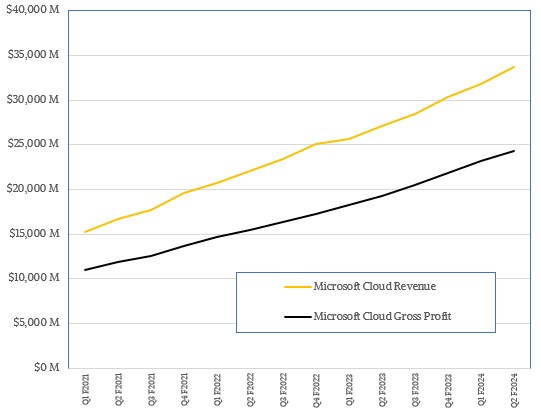

Just to confuse us all a bit who only think about the datacenter, Microsoft has another way it started talking about its cloud business in the past three years. There is a cross-group category it calls rather generically Microsoft Cloud, and that literally means any cloudy hardware or software that it sells, regardless if it is for a PC or a server. Here is how that business is trending:

That Microsoft Cloud business, which Wall Street watches like a hawk because it is a proxy for all kinds of cloud spending, rose by 24.4 percent to $33.7 billion and had a gross profit – not an operating profit, so be careful – of $24.26 billion in fiscal Q2.

Cloud 3: Google Cloud

That brings us to Google Cloud, the cloud builder arm of a company called Alphabet that just about everybody – including us – still calls Google thanks to the eponymous search engine that still drives the majority of its sales more than two decades after it took the Internet by storm.

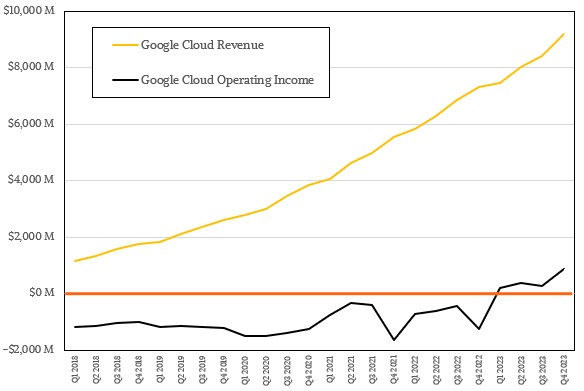

What has not taken the world by storm is the Google Cloud, but the company’s cloud is still growing faster than AWS and is on par with the growth that Microsoft is seeing. With $110.9 billion of cash in the bank and a near monopoly on search and its related advertising, which drives somewhere around 88 percent of its revenues, only a fool would count Google out.

The AI boom helps Google as much as it helps AWS and Microsoft, and it is an innovator in datacenter infrastructure in general and in AI systems in particular. So Google will be a player for as far out as we can see. It can afford to keep plugging along now that it has extended the life of its systems and therefore is able to show an operating profit for Google Cloud.

But it may take a long time before the cloud market breaks into four pieces: 25 percent each for AWS, Microsoft, and Google and 25 percent for everyone else combined. But in the long run, that might be the equilibrium that settles in.

One last thing: We have not tried to pull out the software layer revenue stream off the top of the Google Cloud revenue shown above, separating it into a “real” Google systems business. We need to have a think about that for a bit longer, but we will take a stab at it soon.

What about Oracle?

Alibaba, Tencent, and maybe Baidu come next in size, IBM Cloud after that, and then we get to OCI. Oracle is in a great place to offer custom, tailored cloud, owns its software stack, and can extract profits from customers who love its database, middleware, and application software.