The coronavirus pandemic giveth to Amazon retail business and its Amazon Web Services cloud business, and the pandemic taketh away from the Amazon retail business. That pretty much sums up the third quarter financials of the world’s largest retailer, which is also the world’s largest IT cloud.

You may notice that we are trying to break the habit of calling a massive IT utility a “public cloud,” as AWS and others have called themselves for years. There is nothing public about them at all, like a public library or a public transit system or a public park. IDC has started calling them “shared clouds” in contrast to what we call virtualized on-premises equipment or what IDC calls “dedicated clouds,” but maybe the correct term was right there all along under our noses: AWS is a retail cloud. We are not sure what a wholesale cloud might be, or what to call on-premises IT gear that is cloudy. Anyway, it is Friday and digressions happen. . . .

Let’s pick apart the Amazon and AWS numbers, In the quarter ended in September, Amazon raked in $110.81 billion in sales, up 15.3 percent, but its operating income fell by 21.7 percent to $4.85 billion and its net income was chopped by more than half down to $3.16 billion. Brian Olsavsky, Amazon’s chief financial officer, said on a call with Wall Street analysts that that the compound annual growth rate for all of the company was in the low 20 percent range for the years ahead of the pandemic, but the two year growth rate was 25 percent since the pandemic. So growth has been good at both the retail business in general and the AWS cloud business that is reckoned separately.

But costs for the online retail business have been skyrocketing. Amazon has stomached billions of dollars of extra costs to ensure the safety of workers during the pandemic, plus it is on track to double the capacity of its store fulfillment centers. It has added 628,000 employees and is seeking to add another 150,000 in the United States alone just to support the holiday shopping demand spike. Disruptions to the supply chain – which make Amazon route products from centers further away from users than it would like – as well as wage increases and sing-on bonuses have increased costs by about $2 billion in the third quarter, Olsavsky estimated.

And thus, if you back out the AWS numbers from the overall Amazon numbers in Q3 2021, the Amazon online store and other media and advertising businesses (which are a gnat on the keister of retail business and way smaller than AWS as well) accounted for $94.7 billion in sales, up 12 percent, but the company posted an operating loss of $31 million. Which means it was basically at breakeven and at the net income level booked a modest loss.

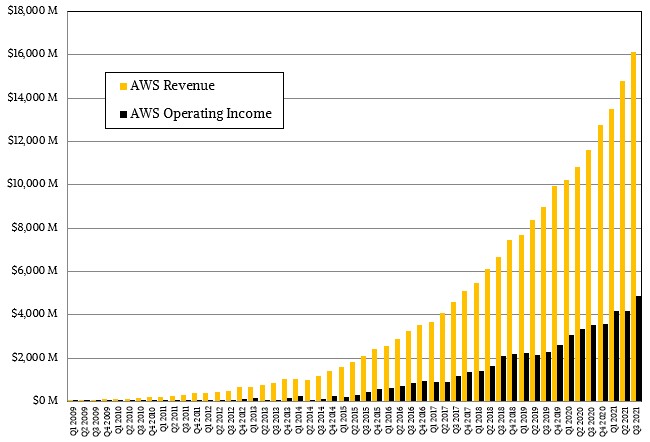

But the AWS business made up for that operating loss and them some, with $16.11 billion in sales, up 38.9 percent, and an operating income of $4.88 billion, up 38.1 percent. People are making a big deal out of the fact that AWS represented all of Amazon’s profit, as if it had never happened before. The same thing happened two years ago in Q3 2019, and it also happened in Q2 2016, Q2 2017, and Q3 2017 by our financial model. (It might have happened more than that. This is as far back as we calculated.) Those extra pandemic costs are hurting the online store business, and so are investments in media and advertising, all of which will abate as we return to normal and AWS gets traction in media and advertising.

On the AWS front, the pandemic has had a very big impact, and that is to accelerate the move to the cloud for certain projects and to increase the capacity that companies already operating from the cloud – think Netflix, Zoom, Disney, whatever – had to acquire to sustain the heavier workloads during the pandemic, which is still kind of happening economically even if we are loosening up a bit as case counts come down and people get vaccinated against COVID-19. Some companies suppressed their cloud spending (particularly those in the experimental and proof of concept phase, we think) as the pandemic struck because they had other more pressing problems to cope with – adding capacity to legacy, mission critical systems, setting up VPNs for end users and customers to get into those systems, and so on. Now they are spending. And we are still Zooming like crazy and watching media like crazy, so those companies just kept growing their usage on AWS, too.

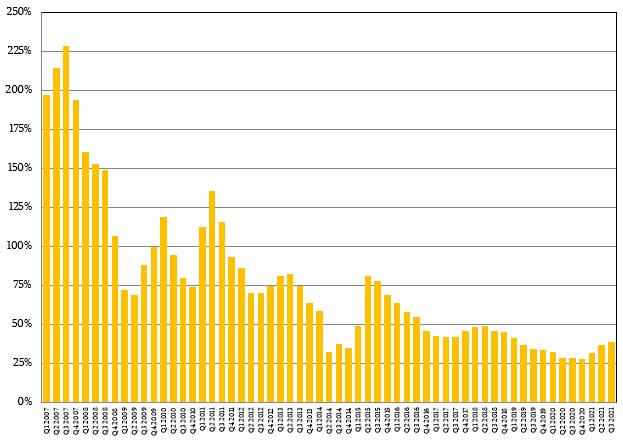

Here is the growth rate of AWS over time, which clearly shows the bump up:

Our model goes all the way back to Q1 2007, when AWS EC2 was a year old, and as you can see, revenue growth tapers off pretty consistently, with the occasional big drop and the occasional recovery. But as we pointed out in February 2019 – with a story called When Does AWS Break Through $100 Billion? – every market has its natural limit and if AWS had kept growing at even 2015 or 2019 rates, it would quickly surpass the entire spending of the US economy or the IT sector overall. That is not going to happen, even if AWS will cannibalize a lot of on-premises IT spending, as it has. Moore’s Law price performance effects drive down IT revenues while capacity increases drive them up, and the interplay of the two results in the actual revenue stream, and that stream eventually has to slow its growth to the natural growth rate of the market overall when everyone has cloudified what they can. We think AWS can get to $100 billion in sales, but we do not think it can get to $1 trillion. So the acceleration of the AWS revenue growth rate from the pandemic has to be taken with a grain of salt, particularly as AWS is still facing intense competition from Microsoft, Google, Alibaba, and Tencent. And particularly as similar rises in the past lead to later declines. The growth rate is a rollercoaster ride, to be sure, but it is heading down to the station.

At one point during the Dot Com Boom, remember, Sun Microsystems looked unstoppable. And then the boom went bust, and then a few years after that IBM actually got its RISC/Unix systems business together and pretty much ended up owning it. However, that is a pyrrhic victory, because the Unix market is 1/20th the size of it was back then. IBM is still at the game with the “Cirrus” Power10 processors, but it just doesn’t matter as much because IBM’s Power chips did not go mainstream in the hyperscale and cloud datacenters.

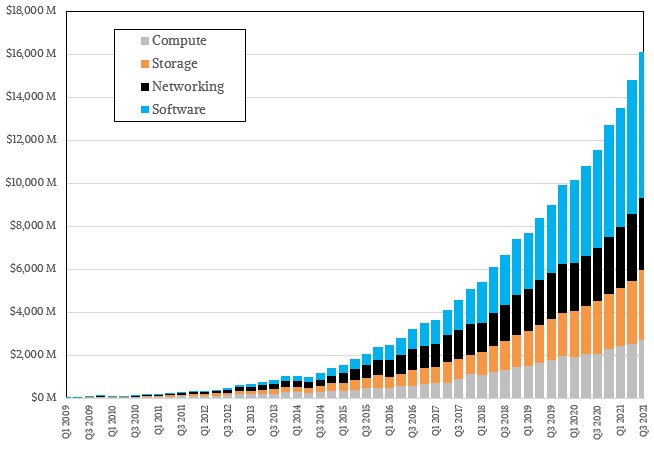

While tracking the revenue and operating profit of AWS is fun, what we really want to know is the revenue split between compute, storage, networking, and software created by AWS and sold as a service. In the absence of any actual data, we have created a model that shows what it might look like assuming that AWS is selling a lot of software services – database and datastore services, data pipelining services, machine language training and inference processing services, and so on – on top of and often including AWS infrastructure underneath. Here is what this revenue split could look like in a stacked bar chart:

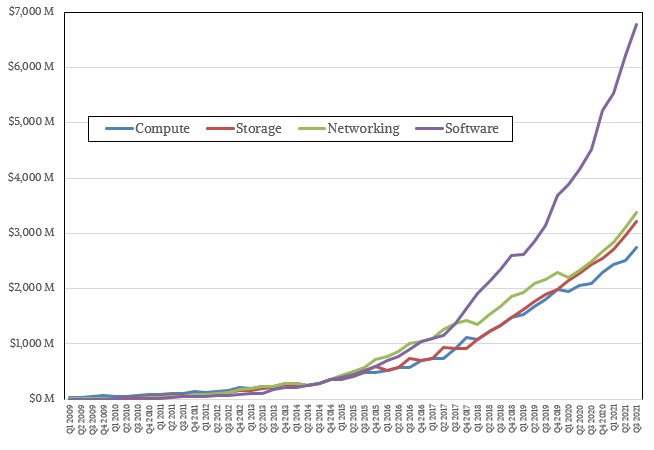

And here is what these four revenue streams might look like in an overlapping line chart that doesn’t stack up the revenues, but puts them side by side so you can see their individual growth:

We think that AWS revenues are material enough for Amazon to start breaking these down a bit, and frankly, it would be good to see more clarity from the other Amazon businesses, such as its own retail (maybe with grocery singled out), third party retail, media production, advertising and such. Olsavsky does not agree, and said as much: “We are very bullish on the retail business. In fact, it is impossible and not productive to even try to separate advertising from third-party from retail. It is all to us part of a flywheel where we service customers. We do it in an efficient way and we earned their trust and their future business. We fight that battle every day.”

So, that probably is not going to happen unless Amazon goes up on the rocks pretty far. Given its retail competition and the seemingly infinite patience of Wall Street thanks to the AWS riches, don’t hold your breath.

Be the first to comment