In the past three decades, there has been no shortage of companies with interesting ideas to solve very specific data storage and retrieval problems associated with high performance computing in some form or another. Many of them raised tons of money, and most of them got eaten by platform incumbents such as Dell, IBM, and Hewlett Packard Enterprise who desperately need something new to sell every couple of years.

What we have not seen, however, is one of these companies break away from the pack and do what EMC did with its Symmetrix RAID 5 disk arrays or Network Appliance did with its eponymous NFS network storage back in 1the 1990s. And that was to make a lot of money reasonably fast and then pull a fair amount of it down to the bottom line fueling further growth and acquisitions that kept them relevant.

Why, we wonder, does it cost so much for storage upstarts like Nutanix, the pioneer of hyperconverged storage, and Pure Storage, one of the pioneers of flash-based arrays, to peddle their products and engineer new ones, so much so that they have nominal profits at best and huge losses at worst? What gives? Or more precisely, what takes?

It is perplexing, and it is perhaps the result of directly addressing the diversity of storage needs in terms of file and object types and sizes and performance and capacity – and something to ponder as compute is heading away from the homogeneity of the X86 compute platform towards an ever-widening array of domain specific processing. Maybe the very act of co-designing hardware and software to fit a very specific purpose means that all compute and storage will be chasing something smaller than a mainstream, homogenous market.

Some niches will be bigger than others, of course. But thanks to the wonders of volume manufacturing – or in this case, the decreasing volumes – everything will get more expensive per unit than it otherwise might have been. But being fit for purpose, everything will deliver better performance, price/performance, and performance per watt for very specific tasks.

The grief for system architects will be figuring out the purpose and finding the fit, something homogenous compute, storage, and networking has not required IT organizations to spend a lot of time sweating about. Creating workflows across domain specific compute, storage, and networking will be the tricky bit going forward.

It is with all of this in mind that we are thinking about the financial results of Nutanix and Pure Storage and how they compare and contrast with upstarts from the dot-com era, EMC and NetApp. And how other storage pioneers in the HPC arena –Vast Data, WekaIO, and Qumulo come immediately to mind – might fare from a financial perspective.

We don’t know how Vast Data, WekaIO, and Qumulo are doing financially except for some hints here and there from their top brass. We honestly hope they will file to go public with the US Securities and Exchange Commission in the new year just so we can get a look at their S-1 filings and actually know what their revenues and costs have been for the past several years. It would be enlightening to see how this next wave of storage vendors is doing when it comes to growing revenues and moving somewhat more steadily and rapidly towards being cash flow positive and – if you can imagine it – actual sustainable profits.

We remain skeptical, but hopeful.

Blasts From The Past

People in the storage business talk like they are the next EMC or the next NetApp, and we understand, as Henry David Thoreau once observed, that you only hit what you aim at so you might as well aim high. But as far as we can tell, the only companies that might be the next EMC or NetApp might be Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, or Microsoft Azure. And even that is stretching it a bit. The conditions in the market three decades ago and now are so different that we are beginning to believe that there can’t be a next EMC or NetApp.

Let’s take a look at some history and some numbers.

EMC was founded way back in 1968 as a clone memory maker, and while it had some reasonable success with that as well as with clone disk array storage for IBM mainframes and minicomputers, things got really interesting in the early 1990s for EMC when it took a December 1987 paper on RAID disk arrays by David Patterson, Garth Gibson, and Randy Katz of the University of California at Berkeley to heart and built the Symmetrix line of storage arrays.

The Symmetrix line came along just as peak IBM mainframe was happening and Big Blue was charging a huge amount of dough for both processing and storage. The Symmetrix machines also coincided with the rise of industrial-strength Unix systems for running the online transaction processing systems and databases – the workloads that were previously on big mainframes. EMC was a pioneer in commercial-grade RAID storage and road the whole storage area network wave up, too, making countless acquisitions along the way with its wealth.

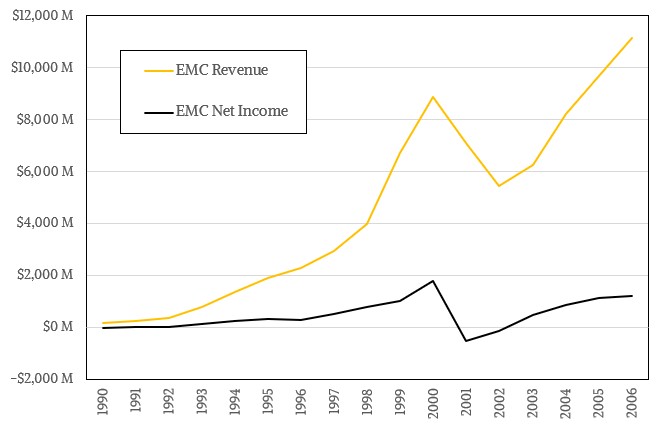

At one point, during the Dot Com Boom, EMC’s market capitalization was over $200 billion, and it was higher than even Sun Microsystems (also surfing on the commercial Internet wave) and General Motors (most definitely not doing that). That was a lot of market cap for the time, and it was well-deserved given how much storage EMC was selling. Take a gander at this:

EMC was messing about with RAID arrays in 1990 and 1991, but when Symmetrix came out in 1992, it became a totally different company. It is as if it had gone into stealth mode and venture funded a new beginning for itself. Revenues in 1993 more than doubled to $782 million and net income rose by 3.4X to $127 million. Revenues kept growing through 2001, when the Dot Com Boom went bust, and then it bled down quite a bit to hit reset and started expanding out beyond its Symmetrix flagship line with the acquisitions of Data General, Isilon, Data Domain, XtremIO, ScaleIO, and myriad storage software suppliers over the next two decades. (And of course VMware.) Excepting two bad years when the first wave of the commercial Internet got wobbly, EMC managed to bring 15 percent to 20 percent of revenue to the bottom line once the Symmetrix arrays and their follow-ons were driving the business.

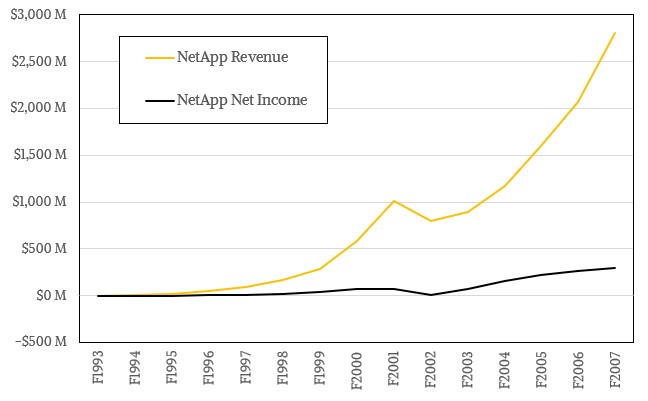

Now, let’s look at Network Appliance, now known as NetApp. The company was founded in 1992 by David Hitz, James Lau, and Michael Malcolm, and in its fiscal 1993 ended in April of that year it had no revenues and booked an $836,000 loss as it was readying its product for market. It booked a $1.8 million loss in fiscal 1994 against $2.2 million in sales of its NFS filers, had a $4.8 million loss against $14.7 million in sales in fiscal 1995 and then was off to the races, riding up the revenue curve through fiscal 2006 and most of the time getting between 11 percent and 14 percent of revenues down to the bottom line over the first dozen years of its sales.

This period is offset by two years with the rise of EMC in calendar 1992 through 2004, and in either case and is roughly analogous to the 2011 through 2022 period where both Nutanix and Pure Storage were ramping. We do not have sales data for either Pure Storage or Nutanix all the way back to 2011. The data for Pure Storage starts in April 2014, which is as far back as it revealed when it announced its initial public offering in October 2015. The data we have for Nutanix, which announced its IPO a year later in September 2016, goes back to October 2012.

In any event, the revenue curves are similar, but the income is mostly red ink, not black, for both companies. And it has been bothering us for years, as readers of The Next Platform are well aware.

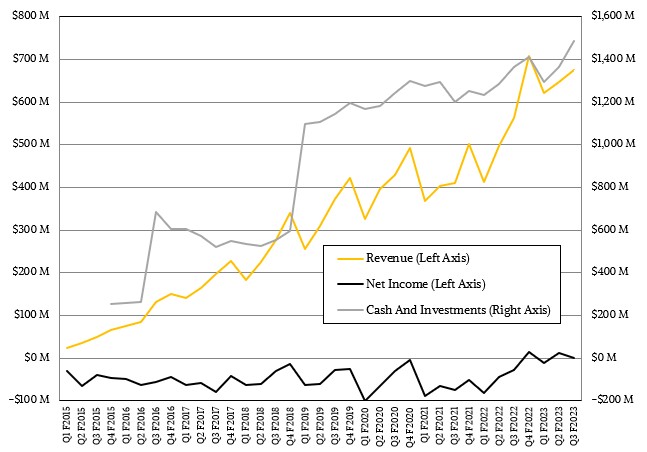

Here is the revenue and income data for Pure Storage:

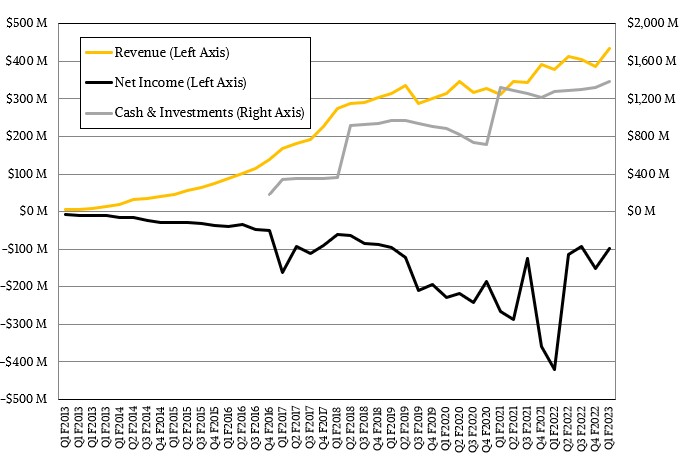

And here is the revenue and income for Nutanix:

The fact that these companies have spent so much money peddling their products for the past dozen years and are still not profitable – and cannot seem to get on a track to repeat what EMC and NetApp have been able to do it their parallel years – bothers us. When we first started covering these companies, we would have never guessed this would happen. Why is it so much harder for Nutanix and Pure Storage than it was for EMC and NetApp. And why was it so much harder for NetApp than it was for EMC, and why is it so much harder for Nutanix than it was for Pure Storage?

The latter question is easier to answer. EMC was selling high end RAID storage and then high-end SAN storage and had a consolidation and performance play that appeals to enterprises. Pure Storage is selling high-end flash storage that can do block, object, and file, and is selling a consolidation and performance play that appeals to enterprises. NetApp had scalability issues, as all NFS and SMB filers did, and that limited its appeal to a certain extent for the high performance computing workloads we follow, and while Nutanix has an excellent converged storage platform that mashed up virtual storage, compute, and networking, penny-pinching HPC centers would never build a supercomputer using it. This is a good platform for consolidating enterprise Windows Server and Linux workloads. And as it turns out, only a relatively small portion of the potential enterprise base that could use Nutanix decides to do so.

The current time is also harder for all of the storage startups and upstarts in another way.

As far as we know, there is no big cloud builder that is buying Nutanix or Pure Storage, or WekaIO or Vast Data or Qumulo for that matter, in anything representative in their vast exabytes of storage. They build their own storage, often create their own file or object systems. They only buy when they have to. Meta Platforms buying Nvidia DGX-A100 systems and InfiniBand networking and Pure Storage flash for the Research Super Computer is a have to, we think, because there was a dearth of GPUs available and Meta Platforms got caught flat-footed because of its desire to only use OCP-compliant servers and storage.

In the end, the 2010s were not and the 2020s are not the Dot Com Boom, when every startup and every incumbent industry player bought a bunch of Unix servers, usually from Sun Microsystems but sometimes from Hewlett Packard or IBM, an Oracle database, and either EMC Symmetrix arrays or NetApp filers (or both). Half of the compute and storage capacity in the world is acquired by eight companies that largely design their own hardware, have it built, and write their own systems software. So the total addressable market is only half what it appears to be. And then, to make matters worse, every day more and more companies start using the cloud and it keeps shifting compute and storage in that direction.

Pure Storage has managed to capture more than 11,000 customers and Nutanix has more than 23,000, but the incremental gains each quarter are relatively small – twice as big for the latter than the former. But Pure Storage is actually profitable over the trailing twelve months, with $2.65 billion in sales, up 34.3 percent, and $14 million in net income (much better than the $207 million loss in the prior trailing twelve months). It has taken a long, long time to get to this point, and you can bet that the company’s top brass wants to bring a lot more to the bottom line. But we have a hard time believing Pure Storage can ever be as big and profitable as a young EMC was.

The numbers are moving in the right direction for Nutanix as well, but the revenue base and the revenue growth is a lot smaller – and the losses are still quite large. In the trailing twelve months, Nutanix had $1.64 billion in sales, up 12 percent, and it posted a loss of $458 million, which is a whole lot better than the $1.19 billion loss it booked in the prior trailing twelve months running through Q1 of fiscal 2022 ended in October 2021.

Nutanix is sitting on $1.39 billion in cash and Pure Storage has $1.49 billion in cash, so they can ride out some economic storms if they come our way. But both companies have to be frugal and still invest in future products and drive sales if they are to get truly and sustainably profitable.

May the next round of storage innovators have an easier time. Qumulo is literally a follow-on by the creators of Isilon OneFS, and Vast Data sells all-flash arrays that scale well (unlike NetApp) and that are waving the NFS banner high for both HPC and AI workloads. WekaIO sells a parallel file system that supports HPC and AI workloads and is sort of a follow-on to Lustre and GPFS but one that also supports POSIX, NFS, SMB, and S3 protocols.

We shall see. We remain skeptical, but hopeful – as usual.

I think part of the problem with today vs back then is that in it’s day Netapp was targetting a much broader market, as you alude to. And EMC was targetting the C-level with the name “BCVs” for it’s marketing. Hard to argue with “Business Continuity Volumes”. But today new sales are are either much smaller in scale, or they are competing with the cloud which is all about large large large scale. So there’s very little in the middle any more. Which is why Netapp is working so hard to get into the Cloud and to be the on-ramp for their legacy on-premiss storage into a cloud setup where the costs (up front, not long term) are much lower.

I’ve been using Netapps since 1996 and I really like what they do. They’re rock solid, have tons of features and really do a great job. But they’re also fighting the 10% problem, where 10% of their customers want 20% of the features, but each 10% wants a different subset. MetroClusters are really key for a very small subset, but those people drive a bunch of revenue. But is it worth it? Maybe.

And once you get the HPC space, the costs of large Netapp clusters is huge, and at that point maybe it makes more sense to run Lustre/Ceph/GFS since you have so much scale and it’s trivial to get reliability and performance by cheaper scaling out of the base product, instead of paying the Netapp/EMC/Pure/Nutanix tax over and over again.

And of course Nutanix isn’t really the same as EMC/Netapp, they’re chasing a different market. It’s hard to justify really reliable systems for the SMB market because people are so cost sensitive and focused on the bottom line. It’s expensive to get past RAID5 clustering or sharding or whatever for the HyperConverged hosting market, since people look at the price of a 2tb SSD for their home system being $300 and wonder why they’re paying $3000 for the same thing in usable space.

Preaching to the choir I am.