What Intel calls “cloud digestion” as the cause of the massive pullback in spending in its Data Center Group is looking more and more like a case of “Epyc indigestion” for Intel, not for the hyperscalers and cloud builders. And the top brass at Intel should be thanking the heavens for their good luck that capacity for advanced fab processes has been severely constrained at the same time Intel struggled to get its server chip act together. If that had not been the case, AMD might be truly cleaning Intel’s CPU clocks.

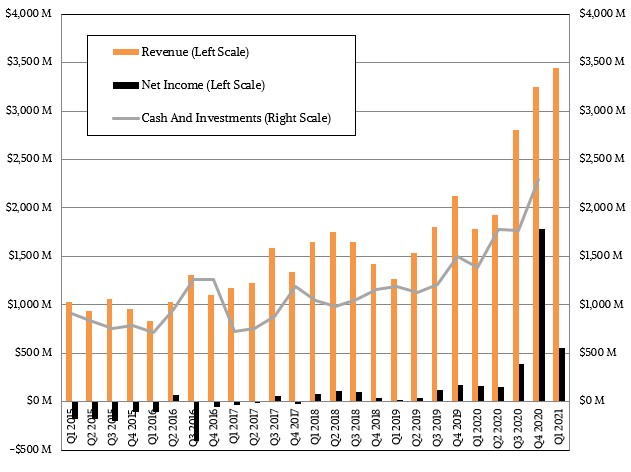

In the first quarter ended in March, AMD was hitting on all cylinders, with its client, server, and game console businesses all up significantly year-on-year as well as up sequentially, delivering a stunning 92.9 percent revenue growth, to $3.45 billion, and an amazing 3.4X increase in net income, to $555 million. All of this good business helped AMD increase its cash hoard by 2.3X to $3.12 billion, which helps cushion the blow on that pending $35 billion acquisition of FPGA maker Xilinx. When you start using “X” instead of “percent” on numbers moving up and to the right, that is always a good sign.

We have contended for years that AMD itself was a little skittish about overcommitting on its wafer supply agreements with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp, particularly given its history during the Opteron server chip era with its own foundry and its spinoff into GlobalFoundries, when it took some pretty big financial hits to negotiate wafer supply agreements down as Intel was ramping up the Xeon server attack during and after the Great Recession. But. On a call with Wall Street analysts discussing the financial results, Lisu Su, AMD’s chief executive officer, said that AMD had managed to negotiate more capacity from TSMC and was able to up its revenue forecast for the year by $1.2 billion to $1.3 billion – most of which we think is going to come out of Intel’s hide in both client and server CPUs.

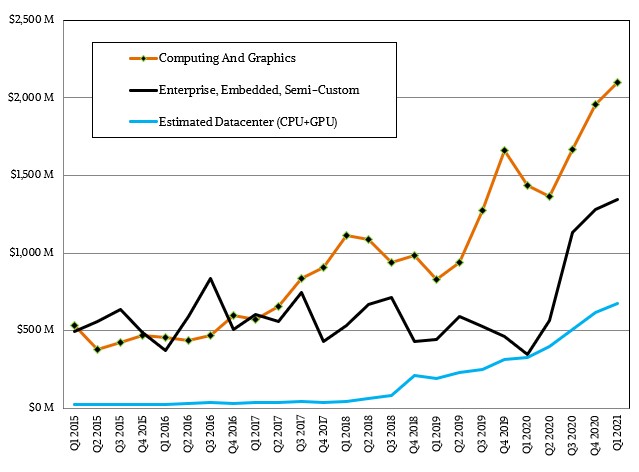

On the server front, it is easy to assume that all of AMD’s success has come from the rollout of the third generation “Milan” Epyc processors, but that is not the case according to Su, who said on the call that server CPU sales were “more Rome weighted in the first quarter compared to Milan, but there was good growth in both.” Heading into the second quarter, AMD is projecting “good growth” for both Rome and Milan, with Milan growth accelerating, and by the third quarter Milan will cross over and bypass Rome. It is always better to have two things to sell, and the pricing across the two generations works itself out with discounts on the older stuff and premiums on the new stuff, as necessary.

When talking specifically about money for server chips, Su said that Epyc CPU sales more than doubled year over year and grew by a “strong double digit percentage” sequentially from Q4 2020. Each Epyc launch has ramped faster than the previous one, and Su added that “2021 marks an inflection point in terms of scale, ecosystem support, and customer adoption for Epyc and Instinct processors.” She added that overall datacenter product revenues more than doubled since this time last year and represented a “high teens percentage” of overall revenue, and that datacenter revenues will grow faster than AMD overall as we progress through 2021. That means datacenter could be as high as 25 percent of sales, we think, as AMD exits 2020. That’s starting from essentially zero five years ago, and that is remarkable and, we always believed, perfectly plausible because markets support competition if competitors bring it.

In the quarter, AMD’s Computing and Graphics group posted sales of $2.1 billion, up 46 percent, with operating income of $485 million, up 85.1 percent. The Enterprise, Embedded, and Semi-Custom business was up by 3.9X to $1.35 billion on the strength of Eypc CPU sales; game console chip sales (which we think were down a tiny bit). Instinct GPU accelerator sales (which we think declined year-on-year) are reported in the Computing and Graphics group, and presumably some of the other GPU cards are added into “datacenter sales” for AMD, too.

If we take what Su said and then apply some model magic to it, we figure that total AMD datacenter sales were up 104.4 percent to $675 million in the first quarter, which represented a 9.5 percent increase sequentially from Q4 2020. We think Epyc CPU sales were up 141 percent year on year to $608 million, up 11.7 percent sequentially, and that Instinct GPU sales as well as some visualization GPUs that get lumped into the datacenter number were off 14.1 percent to $67 million.

Let’s have some fun with math now. AMD’s Epyc CPU sales were up $356 million by our math comparing Q1 2020 to Q1 2021, and Intel’s Data Center Group sales were off $1.43 billion. Some of Intel’s revenue decline is due to increasing price competition from AMD (and some from homegrown Arm servers at Amazon Web Services), and some of it is due to the fact that a CPU sale lost also takes away chipset sales and in some cases a motherboard sale, so there is a multiplicative effect. Intel can counterbalance that by tossing in network interface cards or FPGAs into a CPU and chipset sale for a bigger bundle, but at a much-reduced price. Our point is that a dollar gained by AMD is not a dollar lost to Intel – it is many dollars lost. And, as we have said before, this sets a new ceiling for pricing and that money per unit never comes back. Ever. Ask the failed RISC/Unix server businesses of Sun Microsystems and Hewlett Packard.

The AMD effect on operating income is much more dramatic. It is hard to allocate operating income to Epyc CPU sales, but the Compute and Graphics group, which is sells client CPUs and APUs as well as graphics cards, has been running at around 60-ish percent operating income. We think Instinct GPUs and Epyc CPUs are probably somewhere around 50 percent, which is Intel’s peak in the Data Center Group, so that should be on the order of $304 million in Q1 2021, up from around $126 million in Q1 2020. That’s an incremental $178 million in operating income. If the operating income is higher because AMD charges a more fair price to begin with, fine. Call it a $200 million boost in operating income related to Epyc CPUs.

Intel’s operating income in Data Center Group is down a stunning $2.22 billion year on year in Q1 2021. Every dollar in operating income that AMD has gained has cost Intel about 11X that amount in lost operating income. You have to adjust that for increasing costs on 10 nanometer and 7 nanometer processes for the Xeon line and other factors. But even so, the AMD effect could be a 5X down draft on operating income for Intel’s Data Center Group for every dollar that AMD gains. And on the pure CPU only revenues, that could be against a 2X to 3X revenue multiplier, which is the difference at list price Intel has enjoyed over Epycs for the past couple of years. That means every CPU dollar AMD gains hurts Intel by 2X to 3X, and then it when other factors are thrown in – lost NIC sales, lost FPHA sales, lost motherboard sales, lost chipset sales – that can be a 5X loss multiplier, which translates into a 5X operating income decline multiplier.

This is what we expected, and talked about, six years ago when AMD said it would step back into the server ring. And this seems to be what is happening.

This sounds reasonable:

“We think Epyc CPU sales were up 141 percent year on year to $608 million, up 11.7 percent sequentially.”

But it seems to contradict with this:

“Quarter to quarter, AMD’s Epyc CPU sales were up $356 million by out math”. That does not sound reasonable.

By the first sentence, Epyc CPU sales were up about $64 million Q/Q, not $356 million. Perhaps they were up a little more than that, like $70 million or $80 million, but definitely nowhere near $356 million since AMD says there was a single-digit decline – less than seasonally normal – in semicustom revenue (PS5 and Xbox Series demand is very strong and AMD is churning out as many modules for them as it can). Regarding your estimate that data center GPU sales were down, that seems to contradict what AMD said: “Data center graphics revenue grew year-over-year and sequentially, driven largely by adoption of Instinct accelerators across cloud and HPC customers.”

I also don’t understand your discussion of AMD’s operating income. AMD’s non-GAAP operating income this past quarter was 22% of revenue($762 million/$3,445 million). By segment, the Enterprise, Embedded, and Semicustom segment had an operating margin of 20.6% and the Computing and Graphics segment had an operating margin of 23.1%. Maybe those 60% and 50% margins you are talking about were meant to be gross margins, not operating margins. But AMD’s gross margin for both segments combined was only 46%, and it’s impossible for both of the two segments to have margins above the weighted average of the two.

Regarding your chart, how can “Enterprise, Embedded, and Semicustom” sales ever be equal to data center sales, as it was for Q1 2020? That implies 0 semicustom sales – as if PS4/Xbox One sales went to zero that quarter.

In any case, it sounds like Intel’s claim of a digestion period is somewhat true (though one needs to consider ARM, and the pricing pressure ARM and AMD put on Intel, as well). Intel’s data center sales were off $1.43 billion and AMD’s were only up $70 million. Some was from AMD’s pricing pressure, but a lot was probably from lower demand. Lower demand makes sense as both AMD and Intel were about to launch a new generation of server chips. AMD is much more upbeat for next quarter than Intel overall, but Intel said it sees Q2 data center revenue being higher than Q1.

Before long-term trends are derived from the results of the past year, it must be considered that Intel’s current situation has as much to do with Intel’s problems as it does with AMD’s success. One must consider the possibility that Intel fixes its problems going forward and reclaims some pricing power. Now from Intel’s perspective, the specter of Arm is burning bright in the distance. My speculation is that Arm is currently heavily subsidizing its datacenter efforts to establish its architecture. It remains to be seen what the future competitive landscape will be once ARM is no longer giving away value to its customers, which is likely to happen no matter if NVIDIA buys Arm or if Arm has an IPO – probably faster in the latter case. Will Amazon, for example, still want to be in the CPU-making business?

Well, I want to correct something I said. Enterprise, Embedded and Semicustom equaling datacenter revenue doesn’t mean 0 for PS4 and XboX One sales, rather it means that PS4 and Xbox sales equaled data center GPU sales, if data center GPUs are put in Computing and Graphics and not Enterprise. Even so, that’s hard to swallow.

TNPs $608m number is what they see as the total for Epyc in Q1. Their $356m number is how much it increased by from Q1 last year to Q1 this year. Q1 TO Q1, not Q over Q.

“That implies 0 semicustom sales – as if PS4/Xbox One sales went to zero that quarter.” That’s pretty much what Lisa Su said. In that quarter it was right before new console ramp, so there was negligible sales to MS/Sony at that time (they were selling old stock MS/Sony already had, there were no new console chip orders yet and were not ordering old ones).

Regarding ARM, wouldn’t you say that companies that design/make the ARM server chips are giving away/paying/subsidizing for adoption costs, not ARM itself?

“TNPs $608m number is what they see as the total for Epyc in Q1. Their $356m number is how much it increased by from Q1 last year to Q1 this year. Q1 TO Q1, not Q over Q.”

I suspected something like that, but that’s not what was written. The article has been updated now to say the correct thing.

“That’s pretty much what Lisa Su said. In that quarter it was right before new console ramp, so there was negligible sales to MS/Sony at that time (they were selling old stock MS/Sony already had, there were no new console chip orders yet and were not ordering old ones).”

OK, thanks.

“Regarding ARM, wouldn’t you say that companies that design/make the ARM server chips are giving away/paying/subsidizing for adoption costs, not ARM itself?”

No, I mean Arm itself. FY2015 Arm had a 42% operating margin. FY2016 was similar. Then Softbank took over, resulting in the following: https://www.analysysmason.com/globalassets/x_migrated-media/images/fig1412.png

It stops at 2018 but Arm’s R&D went up more in 2019, not sure about 2020. Meanwhile their revenue did not grow much from 2016 through 2020. How much of that R&D spend went to the IoT Services Group, I don’t know. But, companies used to design their own Arm cores. Ampere, for example, was doing so until they dropped it and switched to Arm-designed cores. Cavium (and then Marvell after they bought Cavium) designed their own cores. They had a ThunderX4 in the works and pulled the plug on it even though they had interest from HPC shops. Perhaps they didn’t see much future in monetizing it commercially if they had to compete with Arm-designed cores. Why should AWS pay Ampere or Cavium for an Arm-designed core when they can just use the Arm-designed cores? A lot of the work has been done already and it comes at favorable value. I get the impression that under Softbank, Arm operated at lower margins in order to push into the datacenter. They spent an extra $500 million per year in R&D (increasing the R&D spend between 2 to 3 times). The wildcard in this analysis is the IoT R&D.

Did you take note of Su’s comment in the call that consoles dropped ‘a bit’, thus Epyc picked that up and then some? Hard to tell from your second chart.

The dropping a bit was “a single-digit percentage sequentially, which is better than typical seasonality.” The and then some is about $61 million, since that’s the Q/Q increase in AMD’s Enterprise, Embedded, and Semicustom revenue.

So the most Epyc could have gained was 9% of $700 million + $61 million which is about $130 million. The chart seems to show a gain for Epyc of about $86 million since Next Platform figured that data center GPU sales were off about $11 million, assuming data center GPU sales are in Computing and Graphics. I used to know which it is placed into but AMD’s counter-intuitive revenue segmentation is hard to keep track of. (AMD seemed to indicate they were up, instead, but that’s neither here nor there concerning the Epyc sales). That would imply semicustom sales off by $25 million or about 3.6%. My guess is that the amount semicustom was off was more likely 3.6% than 9%. So it seems to me the data center chart for Q1 2021 is reasonable, it just needs to have that $11 million add back in. But that would hardly move line much.

Just another reminder that the Instinct GPU accelerator revenue is actually in the C&G segment under Graphics. Please fix this as it’ll show a truer EPYC revenue for AMD and its impact you’ve highlighted so well here. Thanks.

Excellent article once again!

I didn’t think I said anything that implied it was in EESC.

That’s how I read it based on this. Minor detail. Thx.

“The Enterprise, Embedded, and Semi-Custom business was up by 3.9X to $1.35 billion on the strength of Eypc CPU sales but also on some Instinct GPU accelerator sales (which we think declined year-on-year) and game console chip sales (which we think were down a tiny bit).”

I fixed it. Vestigial thought lurking in my head.

“And, as we have said before, this sets a new ceiling for pricing and that money per unit never comes back.”

maybe the money per unit doesn’t come back on those particular products, but the products get renewed every year and it becomes a new game.

For example … Sapphire Rapids will provide CXL, PCIE5, DDR5, AMX tiled matrix operations on bfloat16. If AMD has nothing to offer with those features, Intel can raise prices.

Same can be said for Optane DIMM support. If more and more customers need it and Intel is the only company that provides it, prices can go up.

A few years out, add in the co-packaged optics feature that Intel demoed in March, 2000 on their Tofino 2 switch. Will there be a competitor with a solution to keep those unit prices down?