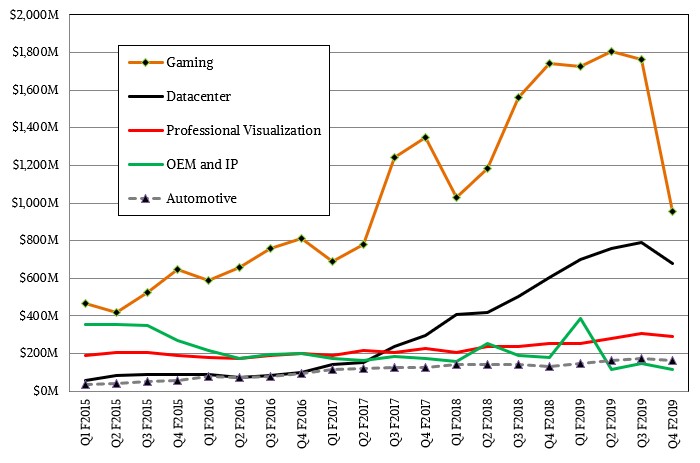

To a certain way of looking at it, Nvidia has always been engaged in the high performance computing business and it has always been subject to the same kinds of cyclical waves that affect makers of supercomputers and enterprise systems. It is just that Nvidia’s waves used to be in an entirely different ocean, one dedicated mostly to GPUs (and now sometimes processors with the Tegra line) for gamers and professional workstation with the Quadro line for engineers.

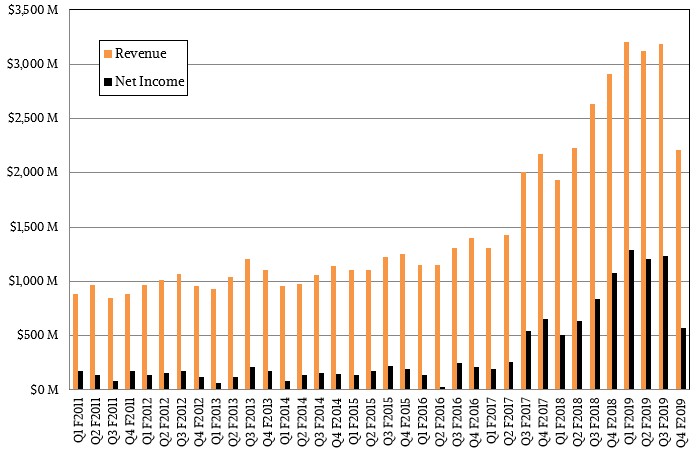

Now that Nvidia is participating in a lot of different markets with its GPUs – which sometimes do graphics, sometimes do compute, sometimes do both at the same time – it has a lot of different waves it is surfing on. This is exciting when all of the waves are rising, as has been the case in Nvidia’s fiscal 2017 and 2018 years ended in January. But it can be tough when a lot of different waves descend, as waves inevitably do, at the same time.

Nvidia, like graphics chip competitor AMD, has been enjoying booming sales of GPUs and CPUs for game consoles and for special tweaks to its GPUs aimed at cryptocurrency miners. Sales of the latter devices have dried up as cryptocurrency mining has moved more to custom ASICs at the same time as the currencies themselves have, for various reasons that smell a lot like tulips in a bubble exactly three hundred years ago, collapsed. Neither Nvidia nor AMD created this cryptocurrency bubble, and they certainly benefitted from its expansion, but now they are paying with tough compares as this cryptocurrency exuberance abates. You make the money when you can as a chip supplier, and not every market behaves predictably, so it is tough to point fingers. That said, this downdraft aptly demonstrates how quickly some aspects of high performance computing can change quickly, often leaving architectures by the side of the road when they make a hard turn or just crash outright. (High frequency trading on Wall Street used to drive a lot more CPU sales, as an example, but the market has shifted more towards smarter trading than faster trading.)

The good news is that Nvidia’s core graphics markets for display and compute are solid, even if they softened in the final quarter of Nvidia’s fiscal 2019, which started in November and ended in January. Colette Kress, chief financial officer at the chip maker, said that Nvidia had gone back over its numbers and figured out what it thought the baseline of its GPU business for PCs, notebooks, and consoles would be absent the uplift from the cryptocurrency mining, and that the core gaming GPU revenue run rate was around $900 million per quarter and ramping with the growth of the “Turing” GeForce product line this year as inventories in the channel get burned and resellers start buying at normal rates again; another $500 million or so per quarter will come from notebook and consoles, leaving the overall GPU graphics business at around $1.4 billion per quarter. If you back that out, then in fiscal 2018 and fiscal 2019, Nvidia was doing anywhere from around $160 million to $400 million in cryptocurrency sales per quarter.

Nvidia needs to sell gaming GPUs to pay for its aspirations in the datacenter, just like Intel has to sell PC processors to be able to invest heavily in server processors. Although in recent years, the cutting edge technology appears first in the GPU accelerators for servers from Nvidia, as it did with “Volta” and trickles down in a slightly improved version with the “Turing” gaming GPUs, which will be used in datacenters for all kinds of workloads, including render farms, video streaming, virtual desktop infrastructure, and machine learning inference, to name a few.

Kress said that sales of the GeForce RTX 2070 and 2080 gaming cards, based on the Turing chips, were lower than expected because as they launched last year there were not enough games available using the machine learning assisted real-time ray tracing, Jensen Huang, Nvidia co-founder and chief executive officer said that the price points and performance points were good, but that Nvidia did not have enough Turing chips to make the midrange GeForce RTX 2060 card, which launched in January at CES. Things will normalize once the channel empties of Pascal card inventories in the next couple of quarters, and as the games come out that can employ RTX, then growth will resume and gamers will do what they do, and that is spend lots of money on hardware. Nvidia is expecting for very good sales of the Turing GPUs on gamer notebooks and professional graphics notebooks, with over 40 gamer notebook design wins as of January and that’s twice as many as this time last year.

Having said all of that, it is tough to stomach a 45.1 percent drop year on year for gaming chip and card sales, which Nvidia did, with sales of $954 million in the final quarter of fiscal 2019. The professional visualization business did better, with sales up 15.4 percent to $293 million, and the datacenter business, which includes sales of GPU accelerator chips, cards containing them, NVLink switch interconnects, system board components for DGX-2-alike clones, and whole DGX-1 and DGX-2 systems as well. There’s some software support in that datacenter revenue, too. In any event, Nvidia’s datacenter sales rose by 12 percent in the fourth quarter of fiscal 2019, to $679 million, but that was after the company experienced a more severe slowdown than it anticipated that started in late December and curtailed sales here. Some datacenter deals set for January were pushed out. Overall sales were down 24.3 percent in fiscal Q4, to $2.21 million, and net income dropped by 47.5 percent to $567 million.

“As the quarter progressed, customers around the world became increasingly cautious due to rising economic uncertainty and a number of deals did not close in January,” according to Kress. “In addition, hyperscale and cloud purchases declined both sequentially and year-on-year as several customers paused at the end of the year. We believe the pause is temporary, and the strength of Nvidia’s accelerated computing platform remains intact. We continue to lead the industry in terms of performance for scientific computing and deep learning, and with CUDA’s programmability, we can continue to expand the value of our platform.”

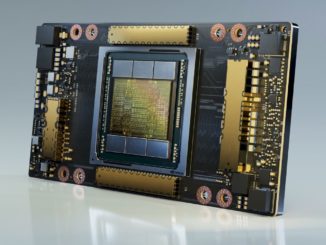

Kress added that Nvidia’s visibility into the datacenter business was low looking out into fiscal 2020, and said that Nvidia does not expect a recovery in datacenter spending before the middle of the year. Nvidia is hanging a lot on inference, and Kress added the tidbit that inference, which Nvidia is focusing on with the Turing T4 accelerators announced last September, represented only 10 percent of its datacenter business at this point.

Huang piped up on the call with Wall Street with regard to the decline in spending by datacenter customers. As Huang said:

“The slowdown is broad based. We saw it across every vertical, every geography. There was just a level of cautiousness across the enterprise customers and the cloud service providers that we have not experienced in a while. I think that it has to be temporary. The computing needs of Earth are certainly not satisfied by what was shipped last quarter, and so I think that the demand will return. Our situation in datacenter is dramatically better year over year, and if you take a look at where we are, our deep learning solution is unquestionably the best in the world. We introduced T4 with inference, which is the world’s first universal GPU. It does everything that Nvidia does, in one GPU, and at 75 watts it fits in every hyperscale server.”

Nvidia says that it has four growth drivers to push the datacenter business up again, with inference and rendering being two already mentioned and the third being data analytics as embodied by Nvidia’s Rapids software stack and finally enterprises just beginning to deploy GPU accelerated algorithms in production, be it for simulation and modeling, machine learning, database acceleration, or analytics.

When pressed again for some more concrete guidance, Huang said that in the short term Nvidia had very little visibility given the uncertainty its own customers are experiencing, but that the company guidance for the year – that sales would be flat to down slightly – implies growth going forward for the company as a whole and for the datacenter in particular.

For the full year, Nvidia’s overall sales rose 20.6 percent to $11.72 billion, and net income rose by 35.9 percent to $4.14 billion, which also works out to 35.3 percent of revenues as net income. This is really good for any company in any business. Wall Street’s unreasonable expectations for explosive growth and for income to be growing faster than revenues always, is always the problem. The ups and downs of the business cycle are like seasonal weather – you just deal with it. Even San Diego has crap weather sometimes. Or is on fire.

Looking ahead, Nvidia is expecting to post sales of around $2.2 billion in the first quarter of fiscal 2020 ending in April, and if you monkey around with the numbers, it is reasonable to expect that fiscal 2020 will be a mirror image, more or less, of fiscal 2019. The issue Nvidia has is that its Q1 of fiscal 2018 was very strong, and it looks like revenues will drop around 30 percent or so year on year even as they stay flat sequentially. But if all plays out, the fourth quarter of fiscal 2020, and possibly the third quarter, will show growth, we think, and profitability for 2020 could be on par with what Nvidia did in 2019.

There are far worse fates. Imagine if Nvidia had not expanded into workstations, or datacenters, or automotive markets, or gaming consoles? It would be half the size it is, and profitability per unit of revenue would probably be considerably lower. Riding the ups and downs of many cycles is far better than just having one cycle, even if sometimes the cycles align against you. In the long run, the area under the curve is a lot bigger, and that is winning.

So…

nVidia is the whole world? Is that the message?

That this was your takeaway from the entire article says more about you than it does about nextplatform or Nvidia.