The appetite for network bandwidth is insatiable, as is that of compute and storage, but our enthusiasm to acquire larger and larger chunks of all of these things is curtailed significantly by cost. If the cost per bit per second comes down fast, and the timing is right, then shifting to a higher bandwidth is relatively easy. This has been happening with 100 Gb/sec Ethernet for more than a year now, and the prospects are pretty high that it will start happening for 400 Gb/sec Ethernet in 2019 and really kick in during 2020.

But this is not just about bandwidth. In some cases, hyperscalers, cloud builders, and HPC centers need more bandwidth, as was the base in the intermediate bump from 10 Gb/sec to 100 Gb/sec, where both Ethernet and InfiniBand took an almost half step at 40 Gb/sec to give the industry time to sort out the signaling and optics that would eventually make 100 Gb/sec more affordable than was originally planned. (You can thank the hyperscalers and their relentless pursuit of Moore’s Law for that.)

In many parts of the networks at hyperscalers, there is a need for more bandwidth, but there is also sometimes a need to solder more ports onto a switch ASIC and thereby increase the radix of the device while at the same time creating flatter topologies, thus eliminating switching devices and therefore costs from the network without sacrificing performance or bandwidth.

All of these issues are in consideration as datacenter networking upstart Arista Networks, which has been making waves for the past decade, is the first out the door with switches that make use of the “Tomahawk-3” StrataXGS switch ASIC from merchant silicon juggernaut Broadcom, which we tore the covers off in January of this year.

The Tomahawk-3 ASICs are the first chips from Broadcom to switch from non-zero return (NRZ) encoding, which encodes one bit per signal, to pulse amplitude modulation (PAM) signaling, and in this case Broadcom has PAM-4 encoding which allows for up to two bits per signal and therefore on signaling lanes that run at a physical 25 Gb/sec, they look like they are running at 50 Gb/sec; if you gang up eight lanes of PAM-4 running at that speed, et voila, you have 400 Gb/sec ports. There are a lot of ways that this top end Tomahawk-3 chip, which has an aggregate of 12.8 Tb/sec of bandwidth across its 256 serializer/deserializer (SerDes) circuits, can have its interfaces carved up to link to the outside world – either natively at the chip or using splitter cables at the port. The Tomahawk-3 can carve down those 256 lanes running at an effective 50 Gb/sec to yield ports running natively at 50 Gb/sec, 100 Gb/sec, 200 Gb/sec, or 400 Gb/sec, or customers can use cable splitters to chop the 400 Gb/sec ports down to two running at 200 Gb/sec or four running at 100 Gb/sec.

There is a second Tomahawk-3 variant, which will have only 160 of its 256 SerDes fired up, that Arista is not yet using, and it will deliver 8 Tb/sec of aggregate switching bandwidth that Broadcom suggests can be carved up into 80 ports at 100 Gb/sec; or 48 ports at 100 Gb/sec plus either 8 ports at 400 Gb/sec or 16 ports at 200 Gb/sec; or 96 ports at 50 Gb/sec plus either 8 ports at 400 Gb/sec or 16 ports at 200 Gb/sec. That 80-port setup is important because that is the server density in a rack of hyperscale-style machines that are based on two-socket server sleds that cram four node into a 2U enclosure and twenty of these into a single rack, for a total of 80 ports. Arista’s initial Tomahawk-3 switches are not making use of this cut-down chip, which is obviously going to be made from partially dudded chips as is common among CPU and GPU chip makers that are pushing the envelope on chip making processes and transistor counts.

A Quick And Big Jump

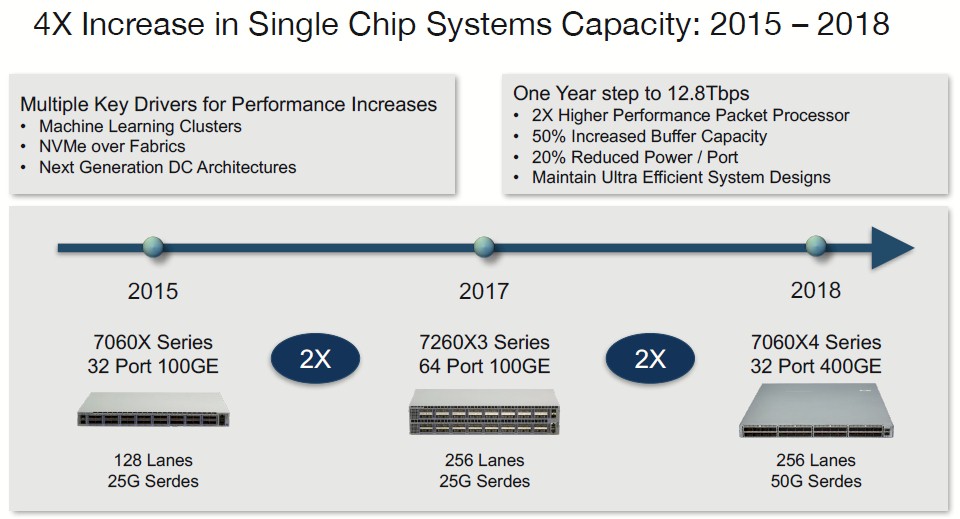

The line of switches that Arista builds based on Tomahawk ASICs from Broadcom have seen aggregate switching bandwidth on the ASICs go from 3.2 Tb/sec in 2015 to 6.4 Tb/sec in 2015, which is a normal Moore’s Law kind of pace enabled by the shrink from 28 nanometer processes that could put 128 SerDes running at 25 Gb/sec per lane on the Tomahawk-1 that made it into devices in 2015 to the 16 nanometer processes in the Tomahawk-2 that appeared in the Arista line in 2017 with 64 ports running on 256 SerDes running at 25 Gb/sec per lane.

The lane count went up because the width of the SerDes doubled, but what is interesting to us is that there was no appetite to have a 32-port switch that runs at 200 Gb/sec. (Or, at least not in the Tomahawk line.) There was similarly no appetite for 20 Gb/sec Ethernet as some sort of stepping stone from 10 Gb/sec to 40 Gb/sec Ethernet, which itself was just a waypoint to 100 Gb/sec. The significant thing, really, is that it is only taking a year to jump from Tomahawk-2 to Tomahawk-3, which is still being implemented on a 16 nanometer process at Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. It will be interesting too see what Broadcom does with a 7 nanometer shrink. . . . But let’s not get too far ahead of ourselves here.

While high radix is important for many, it is not a concern for everyone. Some clustered systems will require the higher bandwidth, and HPC and machine learning shops that can accept an 800 nanosecond port-to-port hop latency (compared to around 100 nanoseconds for 100 Gb/sec InfiniBand or 100 Gb/sec Omni-Path) are going to be able to connect Tomahawk-3 machines up with fewer switches and therefore flatter networks and thereby eliminate some of the hops in the switch fabric and make up for that higher latency compared to really fast Ethernet or blazingly fast InfiniBand or Omni-Path.

Suffice it to say, there are a lot of ways that hyperscalers, cloud builders, and HPC centers might make use of the new Arista 7060X switches. It will all come down to cases, and Martin Hull, vice president of cloud and platform product management at Arista, walked us through some of the math. Let’s say you have 2,048 servers that you want to lash together into a cluster using a single 100 Gb/sec port to the server, to walk through one example of the math that system architects have to do.

“There is no 2,048-port switch out there that runs at 100 Gb/sec per port, so you have to build a topology,” explains Hull. “If you are going to use a fixed 1U switch, with a 32 port by 100 Gb/sec switch, you will need 64 spine switches and 128 leaf switches, for a total of 192 switches, to link those 2,048 servers together. If you take a 32-port switch with 400 Gb/sec ports and have a four-way cable splitter to use it in 128-port mode at 100 Gb/sec, you only need 16 spine switches and 32 leaf switches, for a total of 48 switches. That’s a factor of 4X fewer switches and the cost of the network goes down by a factor of 2.5X.”

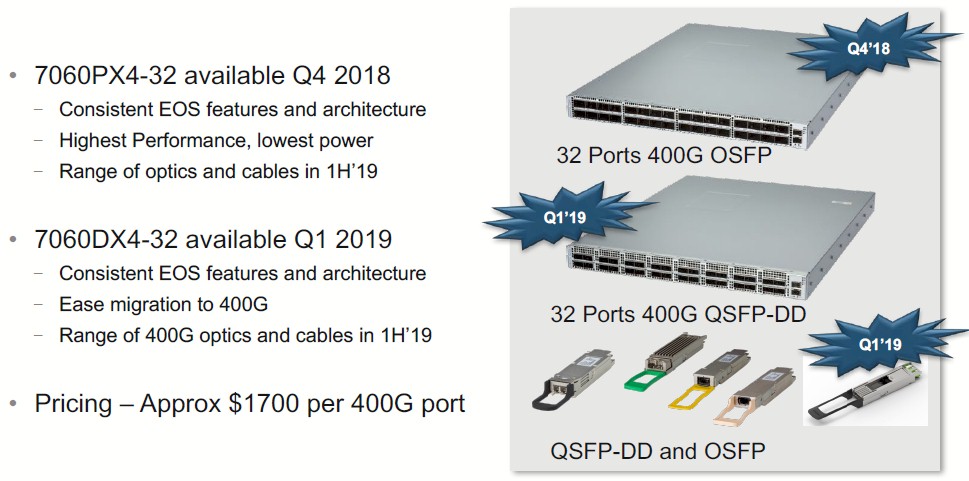

That is another way of saying that a 32-port switch with 400 Gb/sec ports is going to cost only around $54,000 compared to around $34,000 for a 32-port switch running at 100 Gb/sec. (That’s single unit list price.) This is the same ratio that we saw with the jump 40 Gb/sec to 100 Gb/sec switches, and in both cases, the higher radix was well worth the money – and you can always take out the splitters and run the switch in 400 Gb/sec mode somewhere down the line. That $1,700 per 400 Gb/sec port is about what a 100 Gb/sec port cost two three years ago.

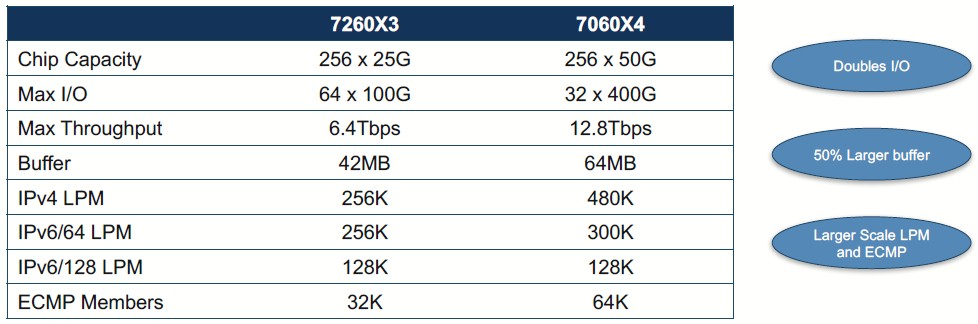

Back when the Tomahawk-3 was unveiled earlier this year, Broadcom was being cagey about how big the buffers were on this forthcoming ASIC. But now we know, from this comparison table that shows the Tomahawk-2 versus the Tomahawk-3 chip:

The Tomahawk-1 chip had 22 MB of buffer memory, less than half of the 48 MB in the Tomawhawk-2. The Tomahawk-3 has 64 MB, which sounds like a lot until you remember that Broadcom has the “Jericho” line of switch ASICs that have truly deep buffers for when the traffic is bursty and the congestion on the network is crazy.

In addition to the increase in the throughput and buffer size, the Tomahawk-3 chip has other enhancement to the IPv4 and IPv6 protocol, boosting the longest prefix match (LPM) table sizes as well as doubling the number of members in the Equal Cost Multi Path (ECPM) routing and load balancing.

The Arista 7060X4 switches based on the Tomahawk-3 ASIC come in two flavors, and they differ from each other in the optics that they support. One supports QSFP-DD optics and the other supports OSFP optics.

The situation is a bit more complex in that Arista is actually going to be delivering an OSFP-to-QSFP adapter that allows it to support existing 100 Gb/sec cables. This will be very useful for those organizations – mostly hyperscalers and cloud builders – that have already deployed some 100 Gb/sec cabling in their datacenters. In any event the switch supporting the OSFP optics that Arista favors will come out sometime in December of this year, and the QSFP-DD version as well as that adapter will come out in the first quarter of next year.

One of the things that is getting harder to bring down is the amount of heat that 100 Gb/sec ports throw off. With the 7060CX-32 switch based on the Tomahawk-1, the switch burned about 7 watts per port, and with the 7260CX3-64 switch based on the Tomahawk-2, Arista pushed a 100 Gb/sec port down to 5.5 watts. With the 7060X4 switch based on Tomahawk-3, that 100 Gb/sec port runs 5 watts, which is another way of saying that the 400 Gb/sec port is 20 watts. That’s a lot of juice, and that is the price you have to pay for higher bandwidth. But it is definitely less juice per bit transferred, even if the line is flattening out. (Some 7 nanometer chips would help on that front, but that shrink will no doubt be used to get baseline signaling up to 50 Gb/sec and with deeper PAM encoding will drive us up to 800 Gb/sec, 1.6 Tb/sec, and even 3.2 Tb/sec down the road. After that, who knows? 100 Gb/sec signaling looks like a barrier right now.)

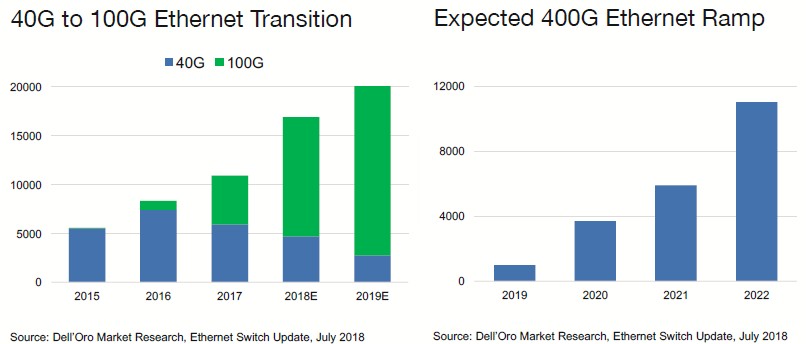

The question we have is how quickly can 400 Gb/sec Ethernet ramp. Here’s the best guesses coming out of Dell’Oro:

“The transition from 40G to 100G was a two-year crossover,” Hull explains. “In 2016, there was not a lot of sales, but in 2018, it crossed over. We are expecting 400G to follow a similar pattern, but you always have to remember that this is future gazing and crystal ball watching. We think that 2019 will be an important but low-volume year for 400G, but 2020 will be the volume year for 400G. That, of course, is predicated on some assumptions. We shall see.”

The initial customers who will be buying 400 Gb/sec Ethernet are, first and foremost, the hyperscalers and some of the larger cloud builders, but Hull says that given the bandwidth available, there will be some HPC centers that go with Ethernet over InfiniBand. Companies building machine learning clusters with very high bandwidth demands – machine learning is worse than HPC when it comes to network load once you scale out beyond one node – are also going to be deploying 400 Gb/sec Ethernet. But probably not the tier two and tier three cloud builders and telcos, and definitely not large enterprises for a while. But, eventually, we will all get there. The economics argue for sooner rather than later.

Be the first to comment