It takes an incredible amount of resilience for any company to make it decades, much less more than a century, in any industry. IBM has taken big risks to create new markets, first with time clocks and meat slicers and tabulating machines early in the last century, and some decades later it created the modern computer industry with the System/360 mainframe. It survived a near-death experience in the middle 1990s when the IT industry was changing faster than it was, and now it is trying to find its footing in cognitive computing and public and private clouds as its legacy systems business is on the wane.

That’s the thing about conglomerates with diverse product lines and long histories with large customer bases: something is always new and going well, but something else is always old and going wrong. It is a sign of maturity, and Google, Amazon, Facebook, and other giants of the modern era have just not been around long enough to see their day. But rest assured, days like IBM is having as it undergoes yet another metamorphosis are in their futures as sure as the Sun rises every morning. (Or more precisely, the Earth rotates around wherever we are to face it.)

The financial results of big companies are an even mix of disclosure and obfuscation, and Big Blue is no exception, even after recatagorizing its business lines in 2015 after it sold off its System x X86 server business to Lenovo in late 2014. This clarifies its business some, but also makes it hard to analyze, too.

We are interested in platforms here at The Next Platform, as you might expect, and IBM is still, despite selling off that $4 billion X86 server business, a major platform provider. Legacy applications persist because change in a large or midrange enterprise means risk, every bit as much as it does for any company like Google or Amazon or Facebook. The product of these companies is change that they absorb, but enterprises are by their very nature conservative because a slower pace of change and a more risk-adverse attitude is what they are often really selling. We don’t really want our bank to change its back-end systems unless it has to because the bits stored on disk drives are actually our money. If we thought our bank was messing around with the core banking systems like Facebook messes with its newsfeed we would move our money. No question about it. So there is a conservative, change-adverse streak in every industry, even if they are innovating all around these core systems of record, as they are called. This is why International Business Machines still exists.

We are old enough to admire IBM’s various platforms, and the parts it played to foster the computer industry as well as to stop it from changing, which only made matters worse because antitrust lawyers for the US government pried open IBM’s machines at the dawn of the mainframe era and kept them open until the early 1990s. And because IBM is a key vendor in the enterprise, even as others have surpassed it in selling and shipping systems, and because it does plenty of research and development and has a slew of industry and domain experts to bring to bear on any problem, we keep a close eye on Big Blue.

IBM has been shrinking for years now, both revenues and profits, as it sheds businesses like PCs, disk manufacturing, printers, memory chips, X86 servers, and other units and adds all kinds of marketing, social network, or mobile integration software businesses (just to name three) and fires up services that are based on its Watson question-answer system and runs them on its cloud and as a feature in its various SaaS products. IBM now talks a lot about cognitive solutions, which often include Watson components, but in truth, a large portion of this cognitive solutions business is still old-school database management systems, transaction processing middleware, and lots of integration and application serving software that runs on its own Power Systems and System z mainframes as well as other competing Windows, Unix, and Linux platforms. It is hard to tease out the new stuff from the old stuff, even if IBM does a rough job with what it calls its “strategic imperatives,” which include mobile, social, cloud, security, and cognitive wares, generated $33 billion for IBM in 2016 – 41 percent of revenue – and are on track to break $40 billion in revenues by 2018 as is the company’s oft-stated long-term goal. Growth in these areas was 14 percent in 2016, and if it grows by 10 percent or so for the next two years, it can hit its target.

“We are moving into a new phase,” declared Martin Schroeter, IBM’s chief financial officer, in a conference call going over the numbers for the fourth quarter of 2016 with Wall Street and that explains as succinctly as we have ever seen how the new IBM sees itself in the future of IT. “The debate about whether artificial intelligence is real is over, and we are getting to work to solve real business problems. As we move into this new era, it is important to understand what enterprise clients are looking for. They need a cognitive platform that turns vast amounts of data into insights, and allows them to use it for competitive advantage. They need access to a cloud platform not only for the capability, but for speed and agility. And they need a partner they trust, and who understands their industry work and process flows. This is where we’re clear and confident about our point of view. Yes, we have world-class cognitive technology, but that’s table stakes. We are building datasets by industry that we either own, or we partner for. Importantly, we have designed Watson on the IBM Cloud to allow our clients to retain control of their data and their insights, rather than using client data to educate a central knowledge graph. And we are using our tremendous industry expertise to build vertical solutions and train Watson on specific industry domains. We are amassing these capabilities, because you need more than public data and automation algorithms to solve real problems like improving healthcare outcomes or navigating the banking regulatory environment. So in this new phase, data, and the business model around data matters, industry matters, and time matters. And that is why Watson is the AI platform for business.”

But don’t expect to see a revenue figure pinned to Watson stuff explicitly any time soon. IBM is too clever for that. The most that Schroeter would say is that Watson is a “silver thread” that runs through its cognitive solutions.

IBM also has high hopes for the commercialization of blockchain, the distributed ledger that was created to authenticate and store the bitcoin digital currency, which is now being applied to various kinds of transaction processing systems. IBM has just inked a deal with Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation, a securities clearing and settlement house, to build a blockchain system, and it is working with Walmart to build blockchain into a food tracking system in China and with Everledger to build a diamond supply chain system to track diamonds worldwide. The SWIFT payments network is apparently looking at blockchain, too. Schroeter told Wall Street (which will be the biggest user of blockchain someday, perhaps) that IBM has had over 300 engagements with clients (likely large enterprises and governments) on blockchain technology and that Big Blue is building a complete blockchain stack.

This reminds us of WebSphere, a gussied up version of the Apache web application server that IBM created for the 1998 Winter Olympics and then turned into product line that has generated untold tens of billions of dollars of revenues and profits for the company since that time – and is still a cash cow at the heart of its software business. By the way, the man who steered that WebSphere product to market and its expansion into a suite of products – Tom Rosamilia – has been running IBM’s Systems business for years now, was the architect of the latest transformation at Big Blue at the behest of Ginni Rometty, and is very likely its next chairman and CEO. We would not be surprised to see him named president at IBM within the year.

It was Rosamilia who was behind the founding of OpenPower consortium and the sale of the X86 server business, and who said a year and a half ago that Power chips needed to have 10 percent to 20 percent of the server market or it was not worth doing. This is a tall order, and IBM does not need – or expect – for its own Power Systems to make up even the majority of Power-based server shipments. OpenPower partners may comprise the majority when Power machinery starts getting its slice. IBM just wants its piece of the action, to sell intellectual property or whole chips to other system makers, and to take a bite out of what is clearly an X86 monopoly in the datacenter, which is controlled with an iron hand by Intel in a manner that is reminiscent of how Big Blue steered the mainframe era. But in the political climate of the past two decades, monopoly is a feature, not a flaw, so don’t expect any antitrust action on this front.

IBM most certainly wants to see its Systems business rebound, of course, and is keen on maintaining the mainframes at the heart of the Fortune 2000-class enterprises and increasing the deployments of Power Systems at these and smaller enterprises as well as among government and academic institutions for simulation, modeling, and analytics workloads. Expect System z14 mainframes to roll out in the second half of this year, and Power9 systems around that time as well if not earlier if Big Blue can do it to steal some “Skylake” Xeon thunder from Intel.

Schroeter said that the current System z13 mainframe line was in its eighth quarter of sales and understandably at the tail end of its cycle, where customers don’t buy new machines but activate latent processing capacity in the machines. At this point, revenues are not booming, up 4 percent year on year driven by a double-digit growth in MIPS capacity shipped, but because that activation costs next to nothing for this capacity, mainframe margins are way up and helped offset IBM’s profit pressure in Power Systems as it pushes Linux machinery against X86 servers. IBM has added 80 new mainframe accounts during the System z13 cycle – we don’t know how many it lost, but there are always some.

IBM’s Unix-based Power Systems revenues were down in the quarter, but Linux-based sales were up by double digits and Linux now drives 15 percent of revenues for Power Systems within Big Blue. In the server market at large, Linux revenue share is probably closer to 35 percent these days, and there is no reason to believe that IBM can’t reach this level with Power Systems, if not push it higher, during the Power9 generation. Sales in the quarter were helped as the US Department of Energy installed Power8-based prototypes – hundreds of nodes, Schroeter said – for the “Summit” and “Sierra” supercomputers that will be the first hybrid supercomputers installed in the world that use Power9 and “Volta” Tesla GPU accelerators when they are deployed in late 2017. Despite this, Power Systems as a whole saw a revenue dip. How much, IBM is not saying.

Storage hardware sales at IBM shrank by 10 percent in the fourth quarter, due as much to the shift from hardware to software in arrays (this is a pricing strategy, just like it is for X86 servers) as to secular shifts in storage architectures away from arrays and towards clustered storage that runs largely on X86 iron. (IBM’s own arrays and some of its clusters run on Power-based systems, of course.)

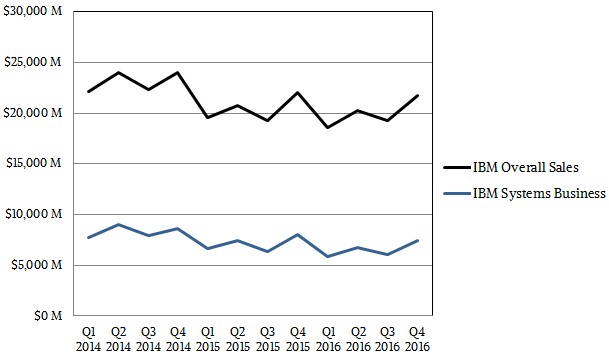

Add it all up with operating system sales, and the IBM Systems group posted external revenues of $2.53 billion with another $156 million in sales to other groups within Big Blue, for a total of $2.69 billion. Hardware sales came to just under $2.1 billion and operating systems accounted for $467 million, both down 12 percent year-on-year. IBM as a whole had $21.77 billion in revenues in the quarter, down 1.1 percent, with net income of $4.5 billion, up just under one point. We think IBM may have hit bottom – so long as there is not a recession in 2017, that is. If that happens, all bets are off, and not just for IBM, either.

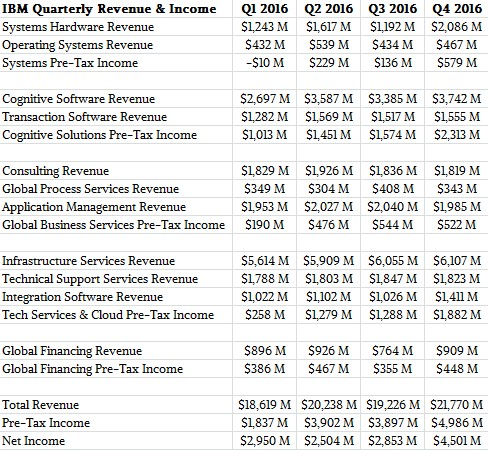

We did an analysis of IBM’s results in 2014, 2015, and early 2016 last spring, so we are not going to repeat all of that again. But here is a summary table of how IBM did, by group and division, in 2016:

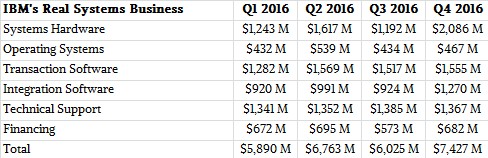

We are always interested in how the underlying platform business at IBM is doing, of course, and as we have been doing for a long time now, we have carved out, as best as we can, what we think IBM’s core underlying systems business – the “real” one that includes hardware and all kinds of systems software on its own platforms – looks like. Here is how we think it did in 2016:

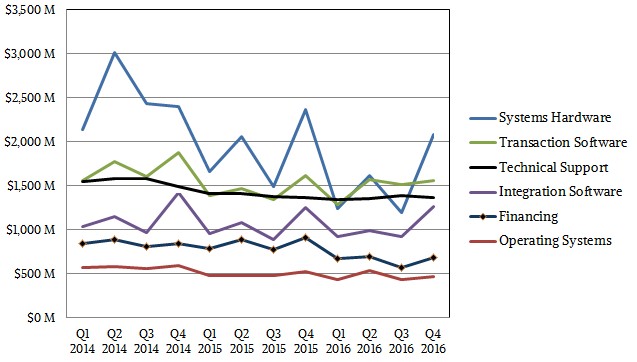

This core underlying systems business averaged somewhere around $6.5 billion per quarter in 2016, and has been declining every year because of product transitions as well as a shift away from Unix and mainframe systems and Big Blue shedding its X86 server business. Here is the three year trend for IBM’s systems business components:

The decline in IBM’s core business is slowing, and we think it may level off or even grow in 2017 and almost for certain in 2018, with a System z14 and Power9 double-pump. As the hardware grows, so will the software on those platforms, given the way IBM sells it. And none of this takes into account IBM’s public cloud business, which should continue growing – albeit mostly on X86 platforms for the next two years, possibly with an increasing sales of Power iron contributing some, too.

Be the first to comment