The biggest benefit that is coming from the separation of the Intel chip design and marketing business from its foundry operations is that Intel’s chip product groups no longer have to shoulder the totality of the immense costs of its manufacturing operations.

The biggest downside is that they these chip product groups will be treated no better and no worse than external customers who also use Intel’s foundries.

As promised by chief executive officer Pat Gelsinger, Intel has just rejiggered its financials to extract Intel Foundry, formerly known as Intel Foundry Services, from the rest of the company. Intel Foundry Services was the temporary name of that part of Intel’s business that allowed outsiders to treat the company as a merchant foundry akin to semiconductor industry juggernaut Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. It was not a very large part of Intel’s business, and its unprofitability was growing as the chip maker was making heavy investments in processes and factories and frankly did not have enough volumes in this business to cover the costs.

We knew that Intel’s fabs were not running at anything near peak utilization, with the PC and server businesses taking it on the chin in the past several years after massive sales during the coronavirus pandemic. But we did not have a concrete sense of just how far under water the thing now known as Intel Foundry was. Well, with the new financial breakdown provided by Gelsinger and chief financial officer Dave Zinsner, we get to see Intel Foundry in its totality, warts and all.

Intel has only recast the financials for the company for the calendar years 2021, 2022, and 2023 and has not provided a quarterly breakdown over that time. We would love to see Intel Foundry numbers back to the Great Recession, or even to 2015 when the company made a concerted effort to supply full stack components for HPC systems excepting main memory. That’s never going to happen.

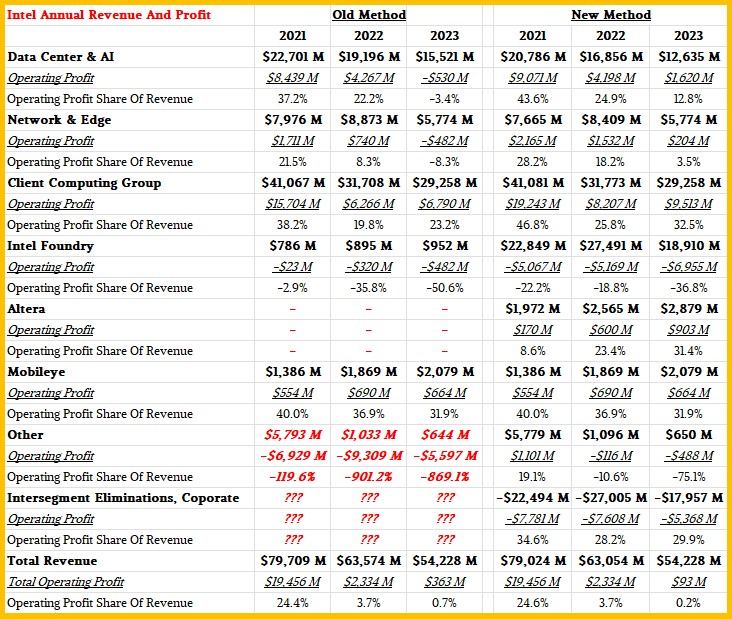

Oddly enough, with the cost allocations for chip manufacturing shifting to “whatever Intel feels like” to “fair market price,” the profitability of the remaining Intel product groups that Intel has not sold off – Xeon products in the datacenter and at the edge and Core CPUs on the desktop – has actually been enhanced. This may be lost on people who did not build their own before and after spreadsheet, as you knew we would. This data comes from historical financials in the Old Method and from an 8-K filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission for the New Method:

Some interesting things to point out in the numbers above.

First, we put the Accelerated Computing and Graphics Group (AXG in the old lingo) into the Others category in the Old Method of financial reckoning when it was reported with a separate profit and loss statement in 2021 and 2022. We didn’t know where to put it any more than Intel did, apparently.

When AXG was disbanded in 2023, pieces of revenue from this unit were distributed to the Data Center and AI group (DCAI), the Network and Edge group (NEX), and the Client Computing group (CCG). Yes, Intel’s names and abbreviations for its groups are inconsistent. Don’t use the word “group” in the group name, just like you don’t use the word “processor” in the processor name. (Thankfully, it looks like Intel is killing off Xeon Scalable Processor, which we always called Xeon SP, and reverting to using the Xeon name.)

In the Old Method for Intel Foundry, Intel was just talking about its external sales of manufacturing capacity. With the New Method, fair market prices for the manufacturing of chips are extracted from each group, and combined with other costs a new operating profit for each group was calculated. As you can see, profits went up in all the major groups. Altera and Mobileye were essentially unchanged.

So if you are running DCAI, NEX, or CCG and you have performance-based bonuses based on the P&L, you deserve a bonus?

The other neat thing is that $3.51 billion in revenues in 2021, $2.34 billion in revenues for 2022, and $2.89 billion in revenues in 2023 was moved out of DCAI. That is $8.73 billion in stuff over those three years, and that seems to us to be material and that also seems to be the Altera FPGA business being separated out. The good news is that DCAI is a little more profitable on considerably less revenues. But that is mostly because DCAI is not shouldering so much of the foundry cost.

Intel Foundry is – to use a technical business term – a real stinker. And it is no wonder that Intel didn’t separate out its financials until after the US government doled out the funds for the CHIPS Act, whereby Intel has received $8.5 billion in direct funding and income tax credits of 25 percent on more than $100 billion in investments, and another $11 billion in federal loans for a combined $44.5 billion.

Some of the mess is Intel’s own fault and some of it is the industry changing back to a more competitive computing environment at the same time that Intel ran aground with its 10 nanometer, 7 nanometer, and 5 nanometer processes. You can’t screw up three major process nodes and not have consequences – particularly when your former near-monopoly in CPUs is under attack and GPU compute takes over nearly half of server revenues and all of those competitors are using a very successful and steady freddy TSMC as their foundry partner.

The server recession, which was made worse by the generative AI boom that started in late 2022, has not helped Intel’s cause, either. Overall server revenues are up even with shipments down, but that is only because an AI server with eight GPUs costs somewhere around $400,000 a pop. Fewer and fewer AI server designs have Intel CPUs in them, Intel doesn’t sell main memory, flash memory, or Ethernet or InfiniBand networking, and it doesn’t have a lot of spare “Ponte Vecchio” Max Series GPUs laying around.

Intel has a certain number of Gaudi2 matrix math accelerators in the barn, and Gaudi3 is on the way this year, both of which will be reasonably well regarded. But let’s be honest, if you can make a reasonably powerful AI accelerator that can beat an Nvidia A100 and match an Nvidia H100 and it can run PyTorch, you can sell all that you can make because Nvidia is very likely already allocated for 2024 and into 2025. But the Gaudi2 and Gaudi3 chips are made by TSMC, not Intel Foundry, and so Intel is only going to get its fair share of TSMC capacity for chip etching and interposer stacking.

Over the past five years, Intel’s share of the CPU market has slipped from 97 percent or so down to 75 percent or so, depending on the quarter. Intel is holding ground in recent quarters, but is doing so at a chip manufacturing process disadvantage – still. And it doesn’t look like it will get much better in 2024, but Intel could start drawing even in 2025.

But Gelsinger is hopeful, as ever, and he is correct that there are political and economic reasons to have a big chip foundry owner located in the US of A.

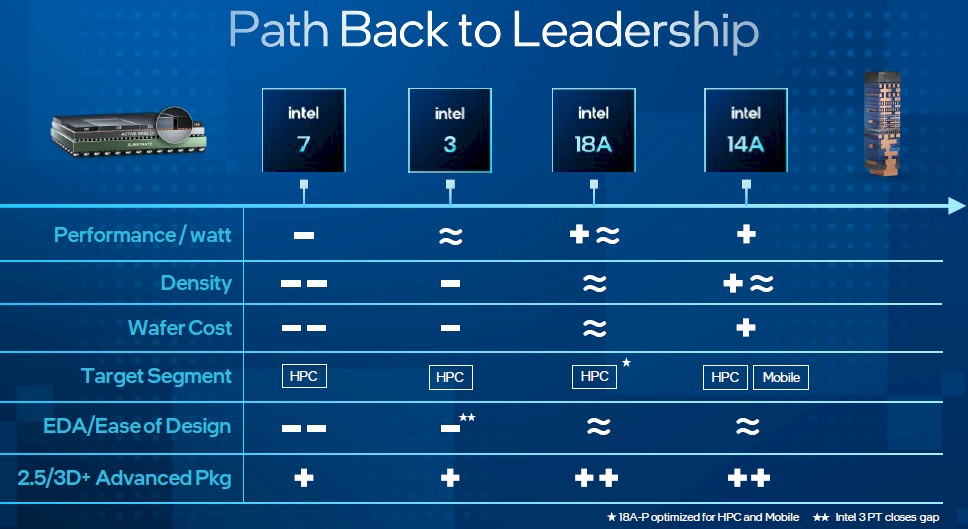

“As we went through our stumble of not embracing EUV and Intel 7, this allowed the industry to catch up. But the cost and complexities of EUV resulted in a flattening of the curve for the entire industry,” Gelsinger said on the call explaining the new numbers to Wall Street. “We have now broken through that EUV wall and turned the corner toward High-NA. And importantly, we’re putting the economics back into Moore’s Law, where it’s going to be uncompetitive for earlier pre EUV technologies and for chips and fabless vendors using those to not embrace the leadership technologies. We have seen through the industry’s history that once a decade, capital technical complexity reduces the number of firms capable of economically manufacturing leading edge transistors. EUV adoption is this decade’s barrier, and AI is driving an explosion in compute needs. Physics is driving density and packaging, and bringing more of these chiplets closer together and to package them in 3D. The rack is becoming a system. The system is becoming a chip, and as we get to the other side of this EUV transition, as you see in this picture, hugely valuable position for Intel in the industry.”

This is the picture Gelsinger is talking about, which lays out the competitive landscape for Intel 7 (10 nanometer) and Intel 3 (5 nanometer) processes, doesn’t bring up the 20A (2 nanometer) process, and jumps right to 1.8 nanometer and 1.4 nanometer processes:

It is going to take a decade to turn Intel around, but the good news is that we are already three years in and Gelsigner has done all that anyone could do to try to right this chipper ship.

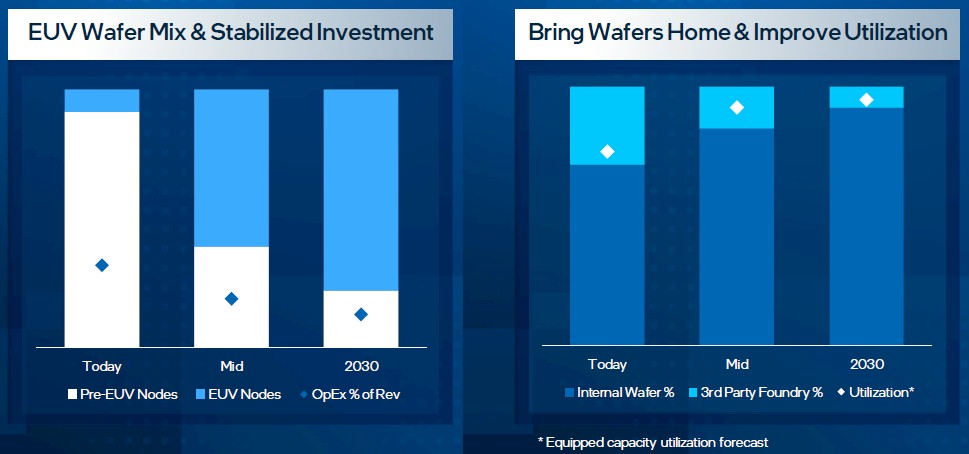

Intel’s profitability depends on becoming a top-notch EUV foundry partner for its own products as well as for others. So far, Intel has $15 billion of deals from outsiders that spans many forward looking years, and most of them are on the 18A process where Intel will have parity – or close to it – with TSMC.

Intel is only getting started on its transition to EUV manufacturing, and its operating expense as a share of revenue is very high, which is causing massive losses for Intel Foundry. But as you can see in the chart above on the left, by 2027 EUV will comprise about two thirds of wafer mix at Intel Foundry, and it looks like it will be about 85 percent by 2023 with operating expenses cut in half as a percent of revenue.

At the same time, Intel will be driving up foundry utilization rates from about 75 percent today to what looks like more than 95 percent in 2030, while also utilizing TSMC for wafers less and less – but not entirely eliminating its own use.

But for now, Intel Foundry looks pretty bad, posting an operating loss of $6.96 billion against revenues of $18.91 billion in 2023, and the expectation is for operating losses to peak this year as Intel finishes up its 5N4Y (five nodes in four years) effort. Intel Foundry is expected to be at break even in 2027 and Intel is targeting 40 percent non-GAAP gross margins and 30 percent non-GAAP operating margins in 2030. Operating losses at GAAP were 36.8 percent of revenue in 2023. This is some startup class lossage.

But, looking ahead, Intel thinks it can build more than $15 billion in annual revenue for external foundry customers by 2030, which is a pretty bug business. The Intel product groups will push at least $20 billion a year, we think, although Intel did not do any forecasting here, and if its competitive position improves in key compute engine markets, it could be as much as $25 billion a year in revenues for Intel Foundry. Be generous and let’s say that Intel can have a $40 billion foundry business that is decently profitable by 2030.

Then, Gelsinger can become chairman, find a new chief executive officer, and breathe a little. But 2030 is a long way off, and Gelsinger had better take his vitamins and keep running.

Thank you for a non-biased look at this company’s transition. As a stockholder, the avalanche of negative articles is difficult to remain holding for 6 more years.

Great analysis! This retro-historical delineation of the foundry’s balance sheet seems like a much better indicator of Intel past performance across its many divisions, an approach that clarifies recent decisions in my view (eg. Altera), and helps in evaluating how profitability may now evolve over time with the more independent fab.

I can imagine Intel’s High-NA-EUV bet to pan out (while TSMC stays with Low-NA-EUV litho to 2030) and generate an increasing customer base (of folks with deep pockets) for the corresponding most advanced nodes. Apple (for example) was apparently happy to reserve “all of” TSMC’s 3nm production for its latest M3, and will likely keep orienting itself towards the most cutting edge processes, whoever has them (IMHO).

If all goes to plan…

See what Xeon 14 nm monopoly bridge collapse at Skylake into Cascade Lake looks like, as it occurred, q3 2017 through q4 2020 at slide 21 compared to Intel monopoly bridge structure during Gallatin and Prestonia 90 nm 2001 through 2002 shown at slide 22.

https://static.seekingalpha.com/uploads/sa_presentations/670/64670/original.pdf

For 2023 dependent Intel total volume which I have at range ‘net’ 309 million to 402 million units fixed cost per unit of production is $70 to $91 that calculated from property, plant, construction and equipment net / 8 years plus R&D for the year. Variable cost per unit is $95 to $123. All up average total cost per unit of production range $164 to $214. Chose to rely on the usual suspect’s annual volumes for Core products and Intel cost per unit of production increases. On a 50% gross margin basis Intel average price per unit then has to be $247 to $321 and anything under the lows contracted out to someone who can make a margin at less than Intel cost which is a structural variable.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing

Intel cannot fail for national security purposes and it is unlikely that sales will run Intel anytime soon, with or without Gelsinger. There will be an engineer at the helm of Intel for quite some time

Nice summary article. One small correction, Intel does sell Ethernet networking products ( one of the largest suppliers)

I meant switches and routers. I will clarify. Thanks for the catch, and of course I know about the NICs and DPUs. Just moving fast.

“But we did not have a concrete sense of just how far under water the thing now known as Intel Foundry was. ”

That was PG’s decision to do 5N4Y … creating parallel research groups for several nodes. Would an independent IFS have made that decision? So, why call “stinker” on the foundry?

It is just a stinker because is is losing a huge amount of money and losses will be worst this year than last year. It is a long way to 2030, but I think Intel can get there. The politics are in its favor. And it can and will create advanced nodes and packaging that people will want. All it takes is one bad earthquake or a war with China to really upset the TSMC applecart, and even if these scenarios are relatively low in probability, they are top of mind and people are swayed by their hopes and fears as much as by statistical analysis.

The paragraph long quote from Gelsinger… it is wonderful to learn Intel has not lost anything on the bafflegab metric.

Which leads us to the “Path Back to Leadership” slide. That is Intel introducing an entire new species of marketing: Visual Bafflegab.

~-+ Well done, Intel.