The edge is continuing to become a place where IT infrastructure vendors need to be, and that includes chip makers, all of whom have strategies to push their silicon to where the data is increasingly being generated and needs to be stored, processed, and analyzed. AMD, armed with the technology it inherited two years ago after closing its $49 billion acquisition of FPGA maker Xilinx, is taking its latest steps to ensure its presence at the edge.

The chip maker this week unveiled the latest addition to its family of cost- and power-efficient FPGAs, the Spartan UltraScale+, aimed squarely at IoT devices that may be small and mobile, but are having an increasingly outsized influence in how enterprises are running their businesses and how tech vendors are assessing IT needs in the coming years.

In talking about the rollout of the new Spartan FPGAs, Rob Bauer, senior manager of product marketing at AMD, ticked off the various trends that are influencing chip makers in how they’re looking at the edge and what needs to go into the processors that are making their way out there.

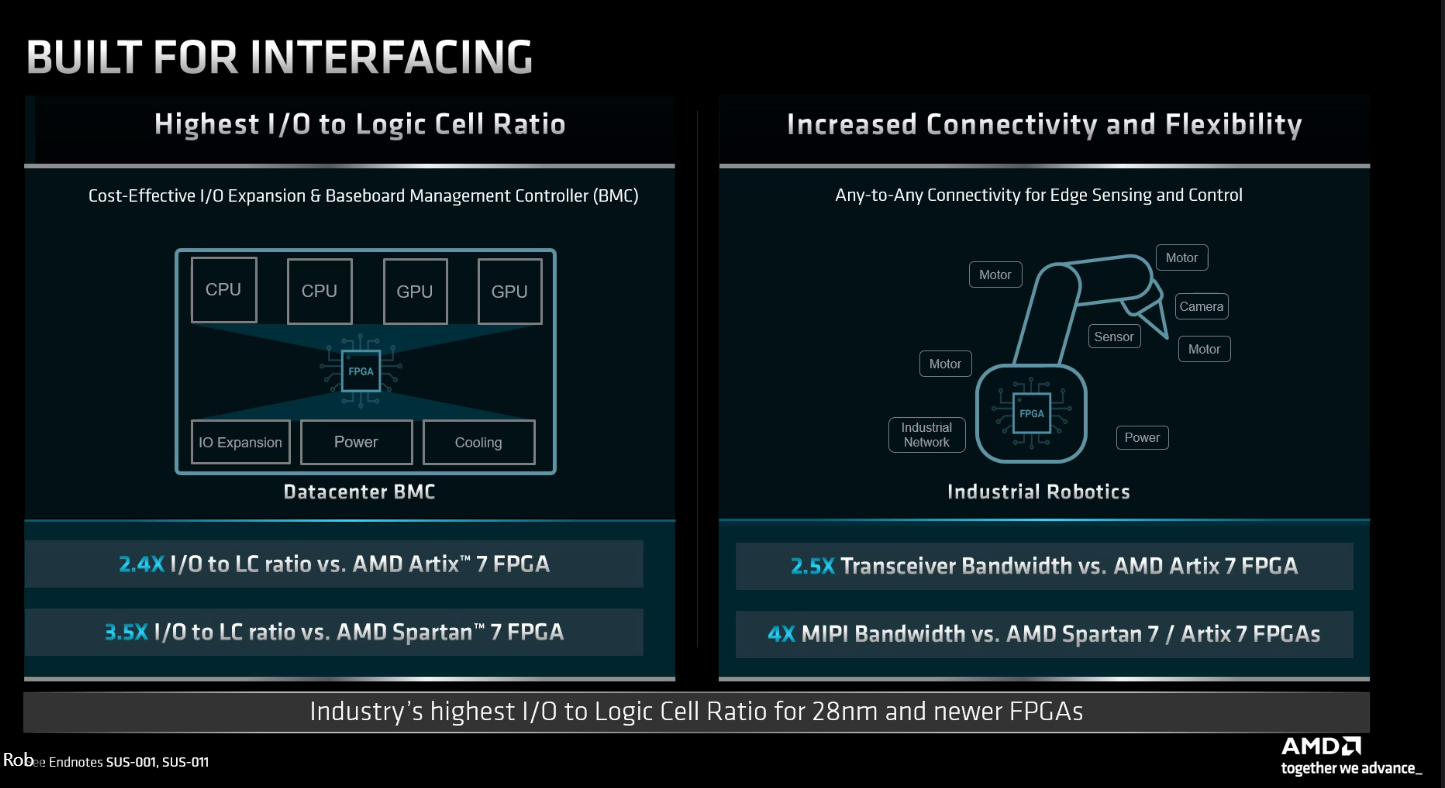

“The first one, and this impacts a lot of the silicon definition, is the explosion of connected devices at the edge and the requirements of some of those devices,” Bauer told journalists and analysts. “What we’re seeing in a lot of these devices an increased requirement for I/O, some more general-purpose I/Os to interface with various sensors, cameras in automatic data capture stacks, motors, etc. That’s really driving the next generation Spartan-class devices.”

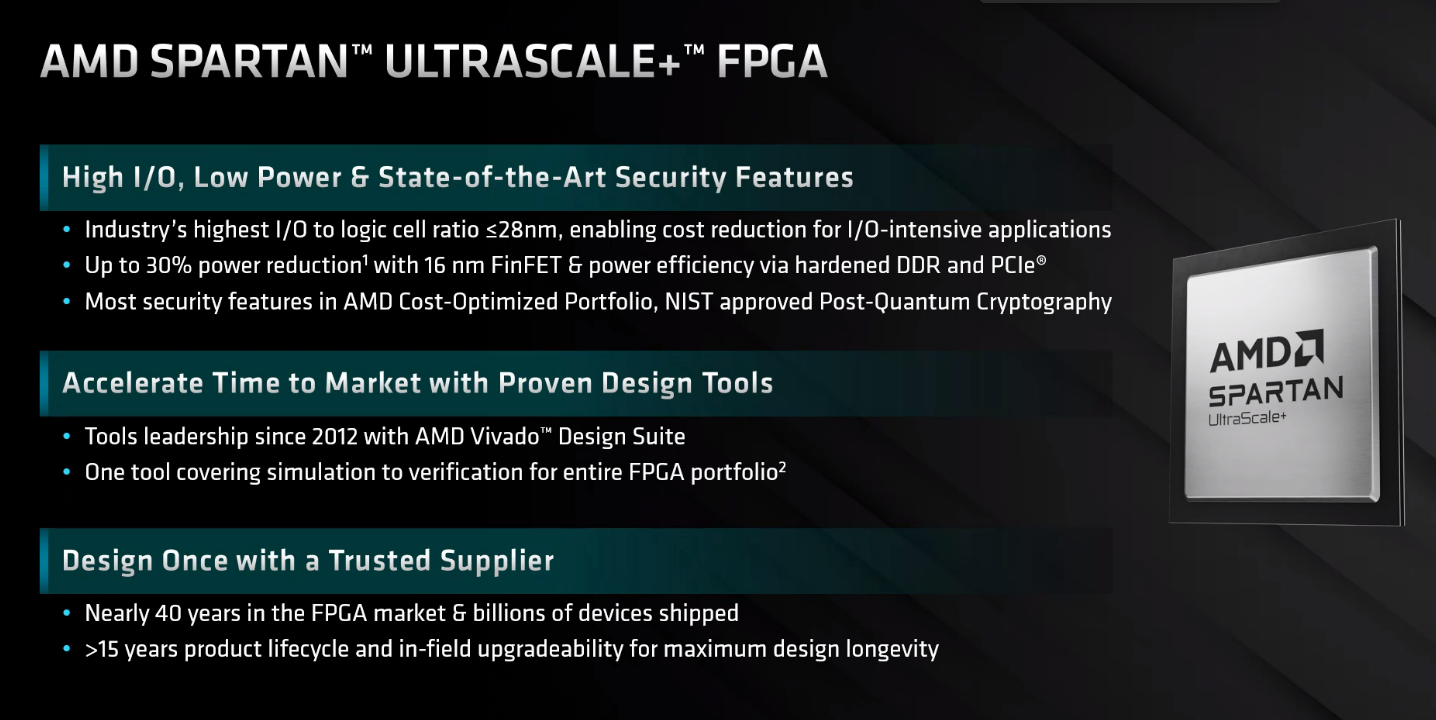

With the amount of data being collected, security and privacy are other factors – “table stakes,” he said – as are making it easier for developers to work with the silicon and the need for longer lifecycles and stability for chip designs at a time when product lifecycles, particularly on the consumer side, are getting shorter.

“New phones are introduced every year with minor and major revisions,” Bauer said. “Sometimes if you look in the industrial spaces – industrial robotics, healthcare, those types of applications – they still need really long lifecycles because they can take years to get a product into production. Imagine spending four to six years just building the thing and getting it into production. You’re going to expect much, much longer lifecycles beyond that. That’s first and foremost in our design selection when putting together a cost optimized product line.”

The focus on the edge by chip makers and other IT vendors isn’t surprising, particularly when you look at the staggering numbers. The proliferation of internet-connected devices – automobiles, cameras, you name it – is accelerating, with the number expected to grow from 15.1 billion in 2020 to more than 29 billion by the end of the decade. By next year, as much as 75 percent of data could be generated outside of traditional datacenters and the cloud.

And the money is following, with global IoT revenue expected to hit more than $1.3 trillion this year and grow to more than $2.2 trillion by 2028.

FPGAs, with their programmable capabilities, small footprints, low power, and low costs, are finding a home at the edge. AMD president and chief executive officer Lisa Su, in a statement announcing the closing of the Xilinx deal, said the acquisition will help the chip maker “capture a larger share of the approximately $135 billion market opportunity we see across cloud, edge, and intelligent devices.”

Intel two months ago spun out its FPGA business – and returned the Altera name to its former Programmable Solutions Group – while a cadre of smaller FPGA makers, such as Achronix, Lattice Semiconductor, Efinix, and startup Rapid Silicon, are looking for traction at the edge.

For AMD, the latest FPGAs – the nine-member Spartan UltraScale+ family is the sixth generation in the Spartan line – will help the company burrow deeper into the space.

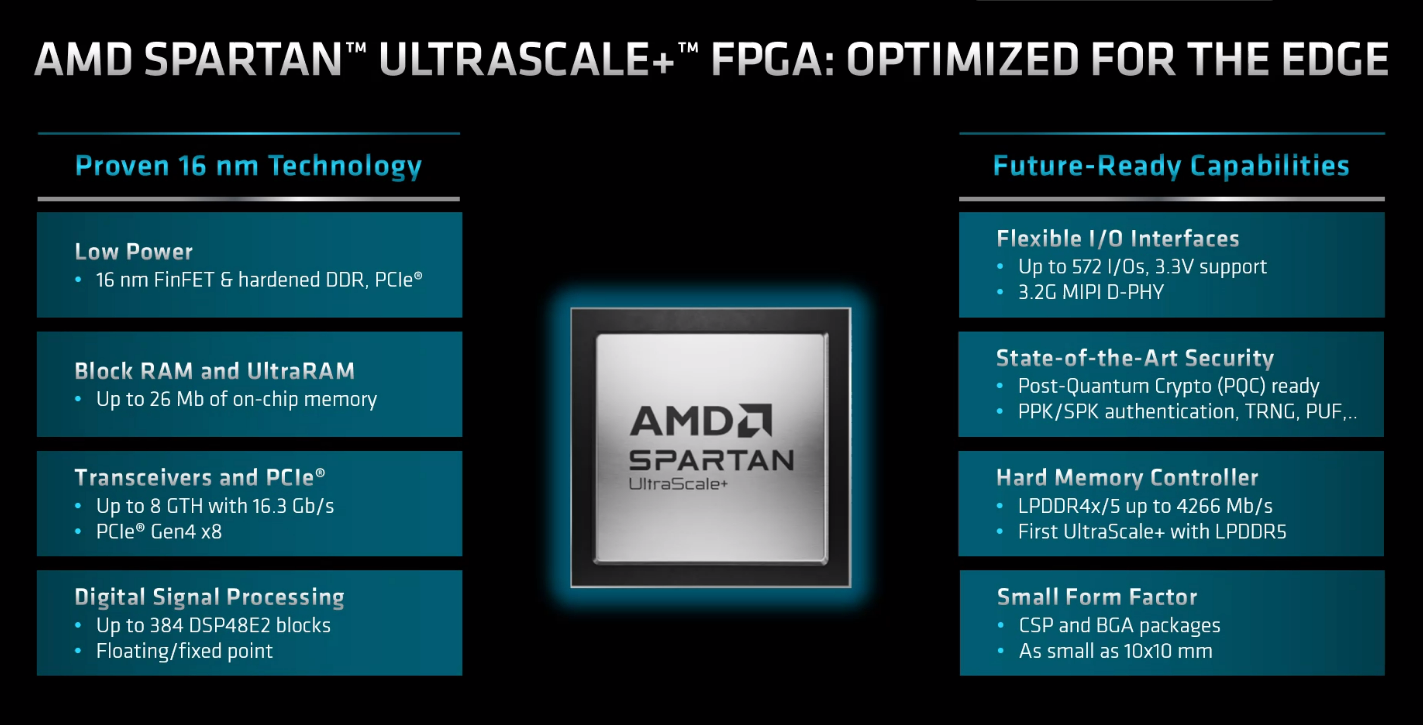

“From a silicon perspective, we really focused on interfacing at the edge,” Bauer said. “What that means is we packed a ton of I/O [up to 572] into these devices. Spartan UltraScale+ offers the industry’s highest ratio of I/O to programmable logic for any device in 28 nanometers or newer. That’s advantageous for I/O-intensive applications and allows you to have more interfacing in a smaller package, which helps with cost reduction, helps with power, and helps with footprint.”

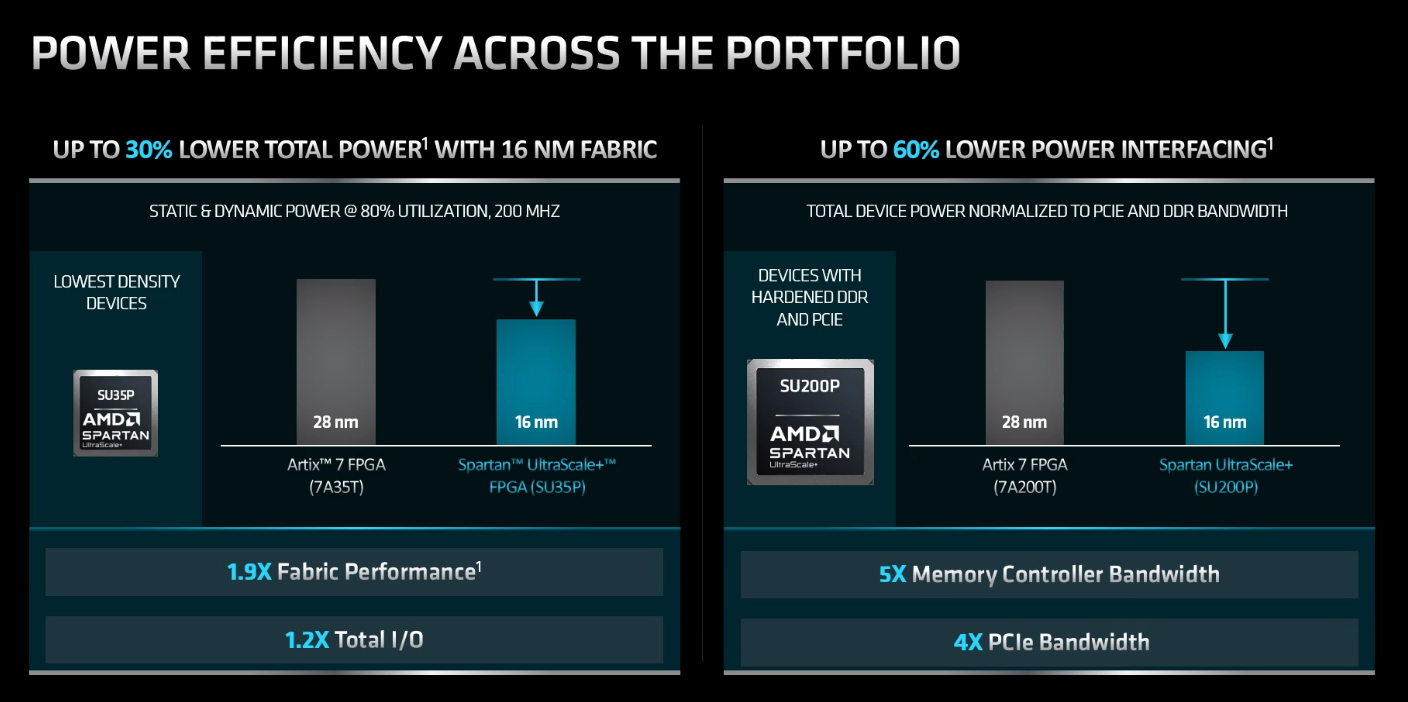

Another focus was power efficiency, with the 16nm FinFET design delivering up to 30 percent power reduction on the lower end of the portfolio over AMD’s Artix 7 FPGAs. It also includes 1.9 times better fabric performance and 1.2 times the overall I/O. In addition, power efficiency also came with how AMD treated memory, giving the 60 percent lower power for interfacing over the Artix 7, as well as five times the memory bandwidth and four times the PCI-Express bandwidth.

“On the upper end of the portfolio, we have also added in hardened IP for memory interfacing and for PCI-Express,” Bauer said. “Historically, a customer, if they wanted a memory interface or [PCI-]Express interface, they may have had to implement that in soft logic, which costs FPGA resources. Because we’ve hardened high-performance memory and PCI-Express, that allows our customers achieve a power efficiency improvement as well.”

There is a range of security features – critical given the location of the data being collected and analyzed – including NIST-approved algorithms for post-quantum cryptography.

Bauer also stressed the commonality of tools, with the new FPGAs supported by AMD’s Vivado Design Suite and Vitis Unified Software Platform, adding that “in the competitive landscape, a number of the other – especially the smaller – FPGA suppliers don’t offer a synthesis tool or a simulation tool, meaning that their customers have to switch back and forth between different tools, which really hurts from an efficiency perspective.”

There also is the importance of the chips’ lifecycle, a key factor for such target applications like industrial healthcare and machine vision.

“We have a track record of over a fifteen-year product lifecycle as standard, but we issue lifecycle extensions, working with our suppliers to secure those agreements,” Bauer said. “The goal here is to help our customers realize the return on their multi-year investments to bring a product to market based on this type of device.”

That lifecycle pushes its usability out to 2040 and beyond. All this is good, but it’s going to take a while to get the new FPGAs into end-user hands. The family of chips is sampling now and evaluation kits should be out in the first half of 2025. Documentation for the Spartan UltraScale+ chips are available now and tool support beginning with Vivado will happen in the fourth quarter this year.

These are great updates of the Spartan line (IMHO): LPDDR5, 16nm, higher bandwidth, lower power, and a footprint that goes down to 10×10 mmm! They should provide a very nice platform for experimenting with edge-oriented Coarse-Grained Reconfigurable Array (CGRA) dataflow architectures, going beyond Verilator simulations and onto the realm of physical realization (eg. this recent Open-Hardware effort from EPFL: https://infoscience.epfl.ch/record/302118/files/CGRA_OSHWorkshop_CF23_Bologna.pdf ).