While not perfectly elastic in the economic sense, where there is a linear relationship between price and volume, we have always contended that the relationship between the price of IT infrastructure and its cost are reasonably elastic.

Amazon Web Services has spent the past decade and a half testing this principle, and is being tested now as companies are skittish that national economies are going to push the world into recession. At exactly the moment when AWS doesn’t want to cut price, it almost has to in order to keep customers from radically cutting back on capacity as they worry about budgeting ahead of, or during, a recession.

Amazon was a user of computers long before it was a supplier of IT capacity, and it is always important to remember that it got its footing during the Great Recession. And therefore it has never forgotten the principle that people expect for the cost of a unit of compute, storage, and networking to go down over time.

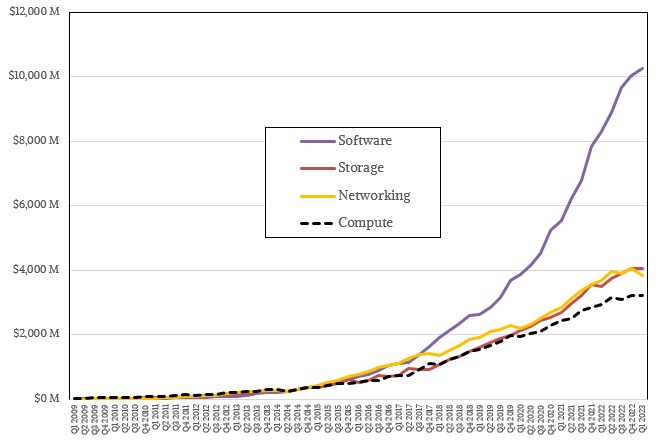

And that means, if you follow the laws of economics, a company like Amazon – and specifically its Amazon Web Services IT infrastructure rental business – has to constantly make it up in volume as well as push down the cost of infrastructure so it can leave a profitability pool to extract between the lowering cost of a thing and the lowering price of what it can charge for a thing.

Some quarters are better than others for illustrating this principle, and the first quarter of 2023 shows that it takes more than many several billions of dollars of capital to execute the cloud game at the high level that AWS plays. Helping customers sometimes means not making as much money now to maintain a relationship over the longer haul. And Andy Jassy, the chief executive officer at Amazon and the general manager of its AWS unit for many, many years, makes no bones whatsoever about it, and neither does Brian Olsavsky, chief financial officer at Amazon.

“Given the ongoing economic uncertainty, customers of all sizes in all industries continue to look for cost savings across their businesses, similar to what you have seen us doing at Amazon,” Olsavsky said on a call going over the first quarter numbers with Wall Street analysts. “As expected, customers continue to evaluate ways to optimize their cloud spending in response to these tough economic conditions in the first quarter. And we are seeing these optimizations continue into the second quarter, with April revenue growth rates about 500 basis points lower than what we saw in Q1. As a reminder, we are not trying to optimize for any one quarter or year. We are working to build customer relationships and a business that will outlast all of us. Therefore, our AWS sales and support teams continue to spend much of their time helping customers optimize their AWS spending so that they can better weather this uncertain economy. This customer orientation is built into our DNA and is how we think about our customer relationships and business over the long term.”

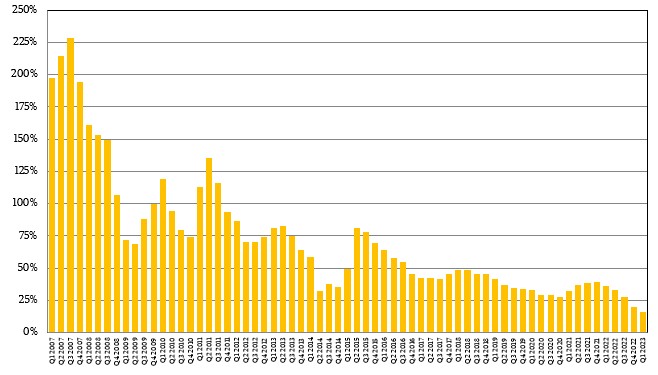

That means for the month of April that the revenue growth rate of AWS is looking like 15.5 percent, and the wonder is whether that will hold steady in May and June or will it drop by a half point each month until it drops to 14.5 percent.

You could build an AI model to use the quarterly growth rates shown above to project it, but if you just eyeball it, there are a number of possibilities. One is that growth falls off a cliff with a big single step down as it has four times in the past. Frankly, the high growth, go-go days of AWS are long gone, but that is to be expected from a company that has an $85 billion annualized run rate serving the IT sector. Amazon is by far the largest direct supplier of compute and storage on the planet, bigger than both Hewlett Packard Enterprise and Dell. We think there will be a flattening decline as AWS saw in 2015 and 2016 and then again in 2018 through 2020.

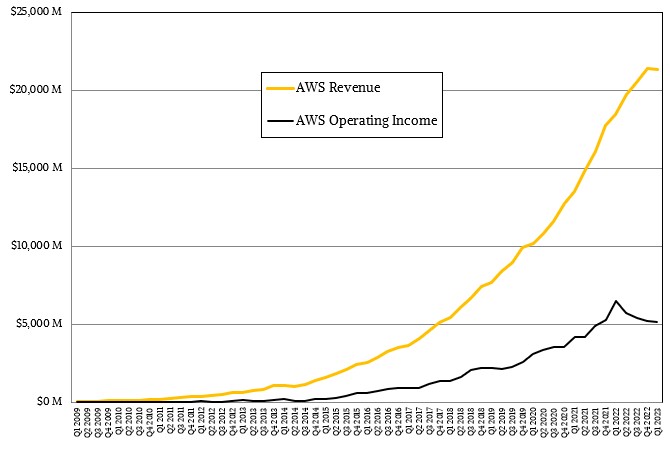

In the quarter ended in March, AWS reported revenues of $21.35 billion, up 15.8 percent year on year and representing less than half the growth rate it saw a year ago and marking the slowest growth in the history of the Amazon cloud operations.

More concerning given that AWS represents all, or sometimes more than all, of the profits of its larger Amazon retailing and media parent, is the fact that operating income for AWS fell by 21.4 percent to $5.12 billion, representing 24 percent of revenues. Q1 2023 was essentially a carbon copy of Q4 2022 for AWS, which is unusual and which probably reflects the uncertainty we are all dealing with.

Parent company Amazon had sales of $127.36 billion in the quarter, up 9.4 percent, and operating income rose by 30.1 percent to $4.77 million. If you extract out AWS, then the rest of Amazon posted a tiny bit more than $106 billion in sales, up 8.2 percent, and the operating loss for the rest of Amazon came to $349 million. All told, Amazon had a net income of $3.17 billion in Q1 2023, and that was after a pretax valuation loss of $467 million on its investment in Rivian Automotive. (There aren’t net income figures for AWS since it is not a standalone company.)

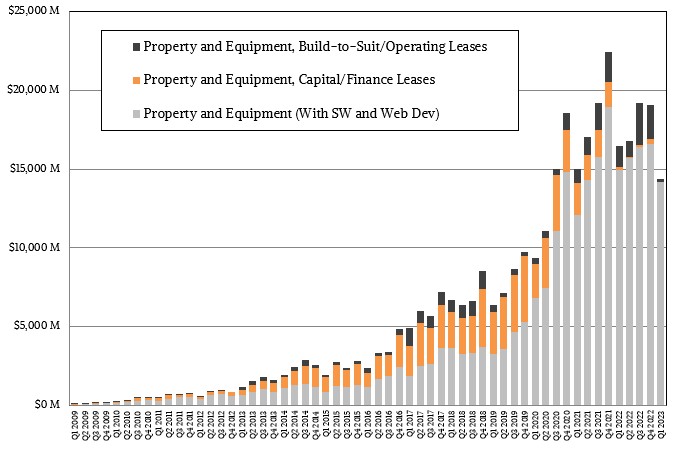

Amazon doesn’t provide a breakdown of its capital expenses, and this is intentional. For those competing with AWS in cloud computing, Amazon is perfectly happy to let everyone freak out and assume most of the money it invests is for datacenters and the stuff inside of them. And for those competing against Amazon in retail, it is perfectly happy for them to overestimate and think that most of Amazon’s capital spending is for warehouses and the transportation network – which is now roughly the size of the United Parcel Service and which was built in a matter of years – it is creating to improve and expand the Amazon Prime delivery operation. The sheer size of both of these businesses and the amount of capital they both require puts up mighty barriers to entry, and if those barriers are artificially higher because Amazon is not specific – well, that’s just killing two birds and getting stoned. Or something like that.

What Olsavsky did say on the call is that Amazon was cutting back on the fulfillment network investments but it would be putting dough into AWS.

“For the full year 2023, we expect capital investments to be lower than our $59 billion investment level in 2022, primarily driven by an expected year-over-year decrease in fulfillment network investments,” Olsavsky explained. “We are continuing to invest in infrastructure to support AWS customer needs, including investments to support large language models and generative AI.”

Jassy actually shows up on the Amazon financial calls, unlike co-founder Jeff Bezos, who rarely did, and had this to say about the situation at AWS.

“In AWS, what we are seeing is enterprises continuing to be cautious in their spending in this uncertain time,” Jassy said. “Customers are looking for ways to save money however they can right now. They tell us that most of it is cost optimizing versus cost cutting, which is an interesting distinction because they say they are cost optimizing to reallocate those resources on new customer experiences. One of the great attributes of the cloud is that you can scale seamlessly up or down as demand dictates, which is not the case with on-premise infrastructure. Customers want help finding ways to spend less during this challenging time. And given that it is best for customers long term, we have been actively helping customers make these adjustments. We have spent a fair bit of time analyzing what we are seeing, and I have spent a good chunk of time myself looking as well, and we like the fundamentals of what we are seeing in AWS. The new customer pipeline looks strong. The set of ongoing migrations of workloads to AWS is strong. The product innovation and delivery is rapid and compelling.”

Wall Street may or may not freak out about this. (Amazon’s stock was down 3.5 percent as we write this.) Newsflash! Wall Street! Growth is always slowing for a new market that explodes on the scene, as cloud computing did on the third try with the creation of AWS in 2006. Of course growth is slowing. It has to or else in a short period of time, AWS would be bigger than the entire IT market and then shortly after that, it would be larger than the entire world’s economy.

What it looks like to us is that AWS is giving back some margins to customers as cost cutting. If AWS has spare compute, networking, and capacity laying around, at the lower price and profit margin, it looks like customers are indeed spending more than they otherwise might. But the growth rate of around 15 percent may be the new normal, as 300 percent, 200 percent, 100 percent, 75 percent, 50 percent, and 30 percent were, broadly speaking, as time went by.

This happens as markets mature and competition heats up, and in the long run, a market grows at maybe twice that of gross domestic product, if the industry and the players in it are lucky. There is nothing to freak out about here. This is how things work when they are working.

My understanding is customer-owned hardware, even if purchased at a premium compared to the hyper-scalers, is often better from a price-performance point of view because the configuration can be optimised to meet specific customer needs, which are often more modest than general cloud infrastructure. Needing to justify every R&D cloud expense to accounting is also a sure way to decrease the efficiency of IT, business analytics and software engineering to the point that any hardware costs are irrelevant.

On the other hand, during times of financial shortfall, people and companies are often forced to do things in less efficient ways. From this point of view, easily being able to scale cloud compute up and down offers a hedge against economic uncertainty where reducing short-term risk is more important than long-term growth. I think this is why the cloud providers won’t be hit as hard as hardware vendors right now.

Well, the other huge benefit of cloud is paying for someone else to do a lot of the engineering around creating highly available networking, and all of the infrastructure an application sits atop. It’s hugely expensive compared to inhouse systems if they are fully utilized. But if your application is small, it may not be worthwhile to invest in the talent to create the necessary reliable infrastructure, and if the application is big, you have to design scalable available infrastructure, which is even harder; the cloud vendors have figured out how to do both. They just charge a lot in order to share that investment.

Amazon is all about (ab)use of scale. They can’t and sure don’t want to help it. And you point out rather well, how with their combination of retail and cloud they can outscale anyone who started with a single focus: fair competition is impossible and that needs adressing.

I think it’s not about ideology but quite simply about gravity: Amazon has reached a size that eclipses nation states and those need to worry about sovereignty when cloud & retail gravity changes who revolves around whom. Somehow the Chinese seem more sensitive to that issue and wise to react before leverage is lost.

Anything near the size where suns, planets and moons change roles just needs to be split, geographically, functionally or any other way or you’re looking at a fundamental societal change instead.