It is hard to imagine how anyone could run Nvidia better than it is being run right now. Even if the $40 billion acquisition of Arm Holdings falls apart because of regulatory concerns, nothing about Nvidia’s current strategy has to change for it to become even more of a powerhouse in the datacenter than it already is.

Nvidia has the most flexible and the most widely used GPU accelerators in the market and the most widely deployed software stack for both accelerated HPC and AI, plus a good bit of data analytics software, too. The homegrown “Grace” Arm server CPU coming in future hybrid systems and can merge CPU cores and Tensor Cores if the market decides it wants to consolidate again – at least for inference. Which we have thought for years would be likely at least among large enterprises. (Hyperscalers and their cloud computing arms can do whatever they want because IT money is nearly free.) It has both high bandwidth InfiniBand and Ethernet networking bases covered, and the BlueField DPUs for offloading storage, networking, security, and server virtualization hypervisors from CPUs in host systems, and NVSwitch interconnects to lash GPUs together into massive compute complexes. It has a systems business that drives datacenter revenues and profits and a channel that eagerly wants a piece of the same action, which is bigger than Nvidia can address by itself.

What Nvidia is not, as yet, is as big as Intel in the datacenter, but there is a chance that day could come. If we had to bet, in the longest of runs, the bulk of compute and network ASIC revenues will be split pretty evenly between Intel, Nvidia, and AMD, with just enough left over for smaller ASIC players (like IBM) and the OEM and ODMs that assemble piece parts out of components and try to make a living at that.

The split might be something like 35 percent to 40 percent for Intel, 25 percent to 30 percent for Nvidia (which has a datacenter business that is about 3.5X larger than AMD right now), and 20 percent to 25 percent for AMD. That leaves a mere 5 percent to 10 percent for the rest of the world. This scenario means Intel shrinks quite a bit in an expanding market, and it assumes that Nvidia and AMD ratchet up the competition like crazy, don’t leave any competitive openings, and just rake it in as they also beat each other over the head in both GPUs and CPUs.

Those are huge assumptions, we realize. The only way to know how this boxing match is going to turn out is to actually fight it. And this is reality, baby, not some simulation that gussies itself up with ray tracing to look real and deep fakes its physics with AI. It will be full of surprises, and sometimes full of shit. And sorrow. And joy. And unexpected turns of good luck. And bad luck. We got ringside seats right here at The Next Platform, and this is only the third round starting.

The second quarter of fiscal 2022, ended on August 1, shows just how well Nvidia is doing despite massive shortages in the semiconductor industry that are hurting all chip makers – including Intel (who talks about it) and AMD (who does not very much). It is hard to say how much more chippery they could sell if they could make more, but that they could sell at least some more seems to be the case. The cryptocurrency miners alone put a dent in the gamer GPU business because of the shortages, driving up prices for “Ampere” cards to the point where Nvidia had to massively cut the hash rates on GeForce RTX cards and create the separate CMP HX product line specifically for mining, using price and performance as controls to separate these two markets absolutely artificially. The gamers are the goose that lays the golden egg, and with only 80 percent of the 200 million gamers worldwide upgrading to modern GPUs, as Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s co-founder and chief executive officer, explained in the conference call with Wall Street to go over the numbers, Nvidia is not stupid enough to just chase the money and annoy those gamers into looking at AMD – and someday soon Intel – GPUs as more cost effective options.

That day could come, but it is far more likely that we see a three-way GPU price war as we are seeing a two-way CPU price war between Intel and AMD right now. As best we can figure, AMD is winning that price war in CPUs right now and has yet to put a dent in Nvidia’s GPU lineup – excepting some very substantial pre-exascale and exascale hybrid HPC-AI systems that will start rolling out later this year and build up steam next year. Intel has a pretty big credibility gap with discrete server GPU accelerators, but the ”Ponte Vecchio” Xe HPC device coming next year is a big step in the right direction.

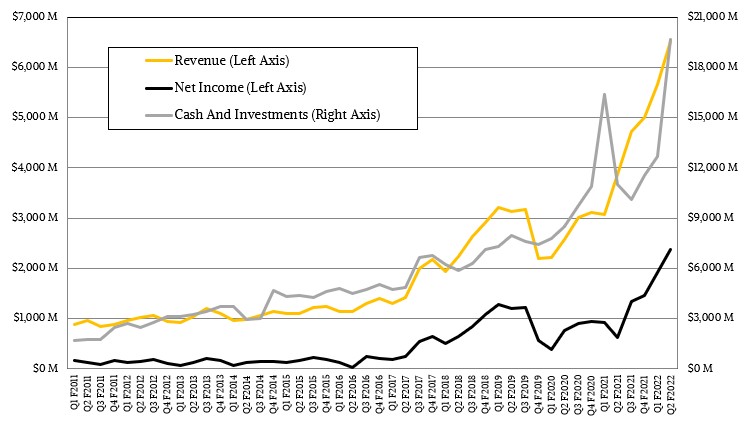

For now, though, let’s focus on the here and now. In Q2, Nvidia’s revenues across all product lines rose by 68.3 percent to $6.51 billion, and its net income rose by 3.8X to $2.37 billion. (In the year ago period, heavy costs, including big increases in research and development, whacked profits, making for a somewhat easier compare.) Operating margins are running at 67 percent and net income margins are a very healthy 36 percent, the second-highest in Nvidia’s history. Revenues this quarter were absolutely historic.

Nvidia exited the quarter with $19.65 billion in the bank. That’s halfway to the cost of acquiring Arm Holdings. Keep it up, and by the time the Chinese government approves the deal, Nvidia will have enough cash to do something truly dramatic. . . . Like buy VMware. (Hold that thought for a minute.)

The indications are that Nvidia will indeed keep it up. Colette Kress, Nvidia’s chief financial officer, said on the call that the company expected for revenues of $6.8 billion, plus or minus two percent, in the third quarter of fiscal 2022 ended in October, and added that excluding CMP HX cryptocurrency GPU sales, the accelerating demand in the datacenter would increase sales of datacenter products by $500 million or so sequentially, and that gaming GPUs would have a slight increase.

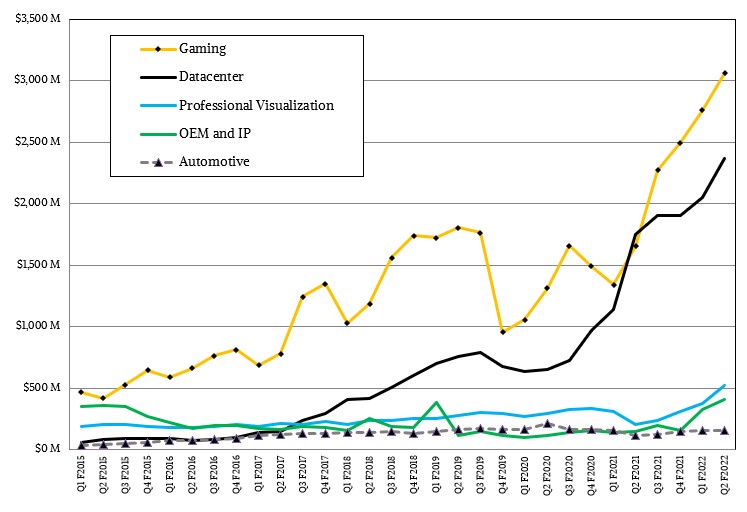

Datacenter sales rose by 35 percent to $2.37 billion in fiscal Q2, but gaming GPUs were the big story, with sales up 85.1 percent to $3.06 billion. The workstation business is finally taking off as artists and techies and executives all build home offices, and the professional visualization line had sales of $519 million, up by a factor of 2.56X. We don’t care about self-driving cars here at The Next Platform – driving is an essential and spiritual activity here – but we will mention that sales in the automotive line were up 36.9 percent to $152 million.

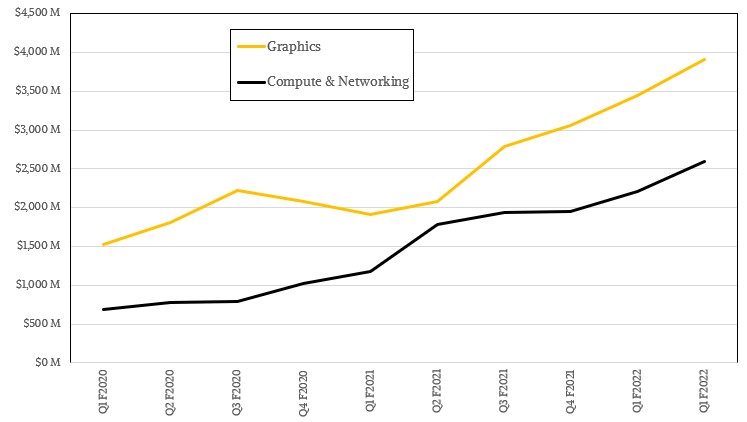

After acquiring Mellanox Technologies, Nvidia started presenting its financials in an additional way, separating its graphics business from its compute and networking business. For a while, it provided operating income figures for these two business groups, but stopped doing that a few quarters ago. (Which was odd.) In any event, the Graphics group had sales of $3.91 billion, up 87.4 percent, while the Compute & Networking group had sales of $2.6 billion, up 46 percent. These are both strong businesses.

We care about gaming inasmuch as it helps provide the research and development foundation at Nvidia for its datacenter products, but what we really care about is those datacenter products. So what is driving the datacenter growth? Huang said that it is really two distinct sets of customers doing distinct things. The first group driving datacenter product sales at Nvidia, of course, are the hyperscalers and cloud builders, who have been adding machine learning training and inference functionality to their applications for the past decade and who are now rolling out big AI projects into their production applications at scale. The second group are enterprises that are adding AI services to their own applications, particularly at the edge and particularly in conjunction with virtualized CPUs and GPUs being managed by the VMware ESXi/vSphere stack. At these large enterprises, there are “tens of millions” of servers that will be running AI at the edge and will be accelerated by GPUs, which Huang characterized as having “billions of dollars of opportunity.”

That off-the-cuff market sizing by Huang might be shy by an order of magnitude. But you get the idea.

Nvidia does not talk about how much of the Compute & Networking business is driven by the former Mellanox products, but Huang said that the Nvidia Networking division had a “solid growth quarter” and that scale-out architectures, particularly at hyperscalers and cloud builders, put tremendous pressure on the network and that the upgrade cycle to 200 Gb/sec and 400 Gb/sec networking was finally happening. Not only that, the advent of the AI revolution with GPU-accelerated machine learning and the exploding size of the AI models – they double their parameter counts every two months, not at the Moore’s Law pace of every two years – was turning every organization into an HPC center. And he put in a pitch for the BlueField DPUs being at the center of the creating the software defined datacenter that VMware and others have been dreaming about for a very long time.

Maybe instead of Intel buying VMware, as we suggested recently, Nvidia should. It could be an equally good fit. VMware is a much larger and more profitable company than Arm Holdings. So this could be Plan B if it comes to that. It would have to be done mostly with cash, or else Michael Dell, the largest shareholder in VMware, might end up being the largest shareholder in Nvidia.

This is an intriguing perspective! Acquiring VMware could give Nvidia a significant boost in the cloud infrastructure space, allowing them to leverage their GPU technology more effectively. It would be interesting to see how such a merger could enhance virtualization and AI capabilities.