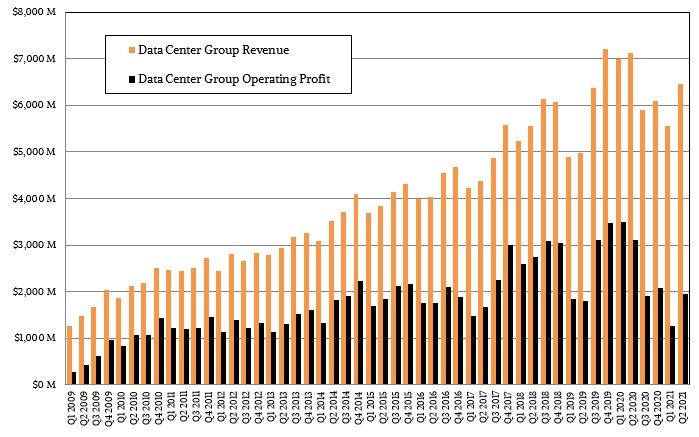

Intel’s Data Center Group has just turned in the third best revenue quarter in its history, just behind the two thirteen-week periods that started off 2020, which was before the coronavirus pandemic had hit and just after it hit and the full effects were not seen as yet. Oh, and when the hyperscalers and cloud builders were buying up server chips like mad. So given all of the general woes of the global semiconductor supply chain and the several acute problems Intel itself is facing, this would seem to be a cause for celebration.

But it really isn’t because the profitability of the Data Center Group – this is operating profits, which is what Intel reports, not gross profits or net income, which Intel doesn’t give out for its groups – is now averaging at a level we have not seen since 2013 and 2014, which the Data Center Group was considerably smaller. This is to be expected with some of the hyperscalers and cloud builders making their own chips or embracing AMD’s Epyc line of X86 server chips or even now Ampere Computing’s Altra Arm server chips. Moreover, some of the work that might have otherwise been done on CPUs is being offloaded to GPUs and to a lesser extent FPGAs, and that has muted Data Center Group’s growth prospects considerably.

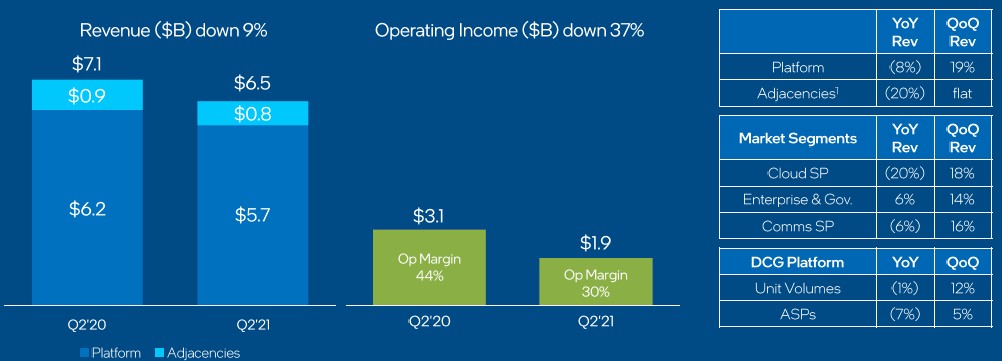

To be fair, Data Center Group managed to grow sequentially thanks to the “Ice Lake” Xeon SP ramp, with revenues in Q2 2021 at $6.46 billion, up 16 percent from the $5.56 billion in Q1 2021; operating profits rose by 52.5 percent to $1.95 billion, which had to be something of a relief given that revenues were down 7.7 percent from the peak Intel revenue in any quarter for Data Center Group, which happened in Q2 2020 when it hit $7.12 billion in sales and operating profits got back to their “normal” level of just a hair under 50 percent at $3.49 billion. For a brief moment, it almost felt like 2013, 2014, or 2015, when Intel was riding high and telling the world it could grow Data Center Group revenues at 15 percent per year indefinitely. Remember that? As we said at the time, we never believed that. No company with 50 percent operating profits can keep competitors away, no matter how hard the engineering task and no matter the investment in time, talent, and money.

And so, the day has come. Pat Gelsinger, who was trained by Intel’s co-founders and who was brought in as chief executive officer earlier this year, called Q1 2021 the bottom for Data Center Group. It’s his job to be sure and to project that. We have our doubts, given the competitive landscape. There are a lot of companies that are looking for a cheaper alternative than Intel chips. So either Intel is going to make less profits on more revenues or it is going to make less revenues at an increasing rate with operating profits that shrink at an increasing rate. Unless, of course, others selling CPU, GPU, FPGA, and DPU compute really screw up, or there is an earthquake and/or tsunami in Taiwan. Neither seems likely, but neither is impossible.

Here is how Gelsinger sees it, according to what he said on a call with Wall Street analysts as he was asked about the “Sapphire Rapids” Xeon SP launch delay in particular and the datacenter business in general.

“Overall, the datacenter business has strong momentum. We really felt that Q1 was the low point, Q2 was gaining momentum, second half the Ice Lake ramp being very strong. And obviously now customers are very anxious and excited by Sapphire Rapids. Huge performance improvements, but also huge feature capabilities as part of that. So we did add a bit more time for the validation cycle, and we are now deep into the validation – it’s in the hands of customers with volume sampling underway, and they’re quite excited about not just the performance capabilities, core count increases, but a lot of the new technologies in the area of new memory, new PCI-Express 5.0, and many of the new features we brought in here for AI performance in particular. So overall, it is going to be a great product and we are expecting to see a very strong ramp of it in the first half of next year. And we think that this will just continue to build the momentum of the datacenter business. As we have indicated, a strong second half is forecast and we are going to build on that into next year with Sapphire Rapids. And the overall roadmap execution is improving as we look for 2023 and 2024 to deliver unquestioned leadship products across everything that we do, including the datacenter.”

In his opening comments to Wall Street, Gelsinger said that the transition to 7 nanometer processes, on which the future “Granite Rapids” successor to Saphire Rapids depends, “is going well,” and that the 10 nanometer ramp, one which Sapphire Rapids depends, is such that during the quarter Intel made more 10 nanometer wafers than it did 14 nanometer wafers. That was a long time coming – like maybe three or so years later than expected, considering that 10 nanometers was supposed to be a relatively easy stop on the way to 7 nanometers. We are not going to get into all of the comments Gelsinger sort of made because it is hosting its “Intel Accelerated” event next Monday to talk about Intel Foundry Services and the other 99 potential customers it has in addition to Intel itself. What we need to know is that more than 50 million “Tiger Lake” Core processors for clients have been made using 10 nanometer processes, the same ones that Ice Lake Xeon SPs use, and another several million are on the way in the “Alder Lake” Core chips that are using the same refined 10 nanometer process that Sapphire Rapids will deploy. Things are bad, but they are getting better. As we said, it is all uphill from here, but in a good way. Maybe the right metaphor is that Intel is climbing out of a hole of its own making. There are a lot of boots at the top, ready to kick it right back down.

In the second quarter, the big surprise was the uptick in spending by enterprise and government customers, with spending up 6 percent compared to the same period last year and up 14 percent compared to the first quarter of this year. Spending on Intel stuff from hyperscalers and cloud builders – what it calls cloud service providers – was down 20 percent year-on-year but up 18 percent compared to the first quarter. Again, Q2 2020 was Intel’s best quarter for Data Center Group in its history, so that is truly a tough compare. Sales to communication service providers – telcos and ISPs and such – were off 6 percent, but up 16 percent sequentially.

Across Data Center Group, unit volumes were off 1 percent and average selling prices were off 7 percent because, to be blunt, Intel has cut price on a unit of compute. And operating profits for Data Center Group we hit by this fact – which Intel dances around and never really admits to – and because there are increasing costs for the 10 nanometer ramp for Ice Lake and Sapphire Rapids, there are 7 nanometer startup costs for Granite Rapids, and there is a greater cost for research and development across Data Center Group as well.

Still, Intel is optimistic and says that it will see “double digit” revenue increases for Data Center Group in the second half. However, in the fourth quarter, expect another profit hit. Intel said in its filing that in the final quarter of 2021 it would be taking a $300 million writeoff for its Intel Federal business, which we strongly suspect is some kind of charge relating to the ill-fated “Aurora” exascale supercomputer that is based on Sapphire Rapids processors and “Ponte Vecchio” Xe HPC GPU accelerators that is being built by Intel and Hewlett Packard Enterprise for Argonne National Laboratory.

Intel didn’t say that, but we suspect that is what it is, and if it is, and Intel and HPE/Cray are still building the system, which had a price tag of over $500 million with $100 million of that going to Cray (which won the deal with Intel before HPE bought the supercomputer maker). Intel may be writing off a chunk of the Argonne contract as a loss and also rolling up a slew of HPC stuff into the carpet before it stuffs it in the trunk of a 1970 Cadillac colored the same as the Intel Inside logo.

George Davis, Intel’s new chief financial officer, said that the charge was related to Intel’s “HPC activities through its Intel Federal” business, and added that “it is crystalized in Q4 at the same time that we execute a contract.” That sure sounds like Aurora to us.

And Gelsinger piped up real quick now after Davis said that.

“I would just say that the HPC business for us – consistent with the reorg that we just announced – we just see a huge opportunity for us once we start delivering our Xe HPC GPU and HPC-specialized versions of the Xeon product, we just see a great opportunity. And the reorg brings more focus on this business, so even though there is the one-time charge in Q4, we see this as a great business for us in the long term and one that will bring many technological, market, and business benefits.”

Over the long haul, both Davis and Gelsinger said that there was no reason that Intel could not get back to the historic margins it had in the Data Center Group. We would argue it already has, and that the run from 2016 through 2020 was the ahistoric margin time. Anything is possible, particularly if the competition in foundries or XPU designs have their own issues. Everybody gets a turn in the hole, after all. But hope is not a strategy, and you can’t count on competitors failing so you can win. We suspect Intel will not reach such margins sustainably ever again, and a feisty Intel will hurt the margins of others as it fights.

“We suspect Intel will not reach such margins sustainably ever again …”

A surprise conclusion, apparently based on some idea that Intel will never again have IP worthy of high margins.

It isn’t hard to note Intel’s leads vs AMD on pcie5, cxl, ddr5, 3D fabrication, Optane memory, VRAN, silicon photonics, any of which could lead to products with significant performance advantages in the data center.

It isn’t that Intel won’t innovate and compete. It is that others will be innovating and competing, too. I didn’t say they would not have any margins. But the highs set are the unnatural condition.

Intel has been feeding the R&D for years… 15 years on silicon photonics, for example, and similar investments in Optane and 3D fabrication.

Intel annual research and development expenses for 2020 were $13.556B, a 1.45% increase from 2019.

Intel annual research and development expenses for 2019 were $13.362B, a 1.34% decline from 2018.

Intel annual research and development expenses for 2018 were $13.543B, a 3.9% increase from 2017.

I’m not saying they will start innovating and competing. I’m saying they have a recognizable treasure trove of IP that is the result of many years of expensive research, and that is just now being turned into products.

There is no way I am stupid enough to count them out. And for the record, I didn’t count AMD out, either. I wished I didn’t have to count Sun Microsystems out, and some days I wish for a Sun revival based on Ampere Computing Arm server chips and the kind of real hardware engineering that the former Sun and the improved Oracle once did. And not just for its own Oracle Cloud. Of course, Ampere Computing can be the basis of any new hardware vendor. Why not?

Xeon Ice Lake sample volume 1K AWP on channel holding data is $2392 that is 1% more than Xeon average 1K back through q3 2020.

Figure the discount anyway you like MC = MR = P at < 50% Intel historical profit maximizing or hyperscale price maker at 80% off Intel 1K equals on average $478 per unit gross / DCG revenue statement equals 13,598,326 units for the quarter. 13.5 M units is down by 1/2 on channel inventory data analyst's Skylake/Cascade Lake on v2/v3/v4 volume comparison defining Skylake / Cascade Lake peak output per quarter whose estimate is free from this analyst pondering what really is DCG INTC 10K revenue. One really can never tell on the amount of component volume thrown into any procurement as del credere brokerage incentive to close a sale.

$478 per unit means a lot of Silver? The channel knows what to do with Silver 2P. Where Ice margin has not really improved over fully depreciated 14 nm+ Cascade Lakes? At least on channel inventory holding data assessment?

Pursuant Ice Xeon Platinum = 20.83% of volume, Gold = 55.83% of volume and Silver = 23.33% of unit volume;

40C = 5% of unit volume

38C = 5%

36C = 4.16%

32C = 15.83% split 6.67% Platinum and 9.17% Gold

28C = 19.17%

26C = 1.67%

24C = 1.67%

20C = 5.83% and its all Silver

18C = 11.67%

16C = 17.50% split 10% Gold and 7.50% Silver

12C = 10% split 2.50% Gold and 7.50% Silver

10C = 2.50%

8C = 0%

On the CCG side channel inventory holding data shows Core primary production current generation q2 1K AWP at $385 up 9% from the average back through q3 2020. On DCG/CCG 10K financial reconciliation on channel holding data this analyst has Core volume discount at 30% off 1K = $269.50 / CCG revenue statement = 37,476,809 units. One could argue closer to $176 net historical, okay, but on DCG Intel needs the margin but let's do it anyway; CCG q2 1K / 2 = $192.50 in this example MC = MR = P for 52,467,532 units sold in q2.

Channel inventory data does lag and currently sees minuscule Tiger H octa/hexa volume. Channel data does record what appears to be Ice Lake U and Comet U mobile and Comet S desktop end of q2 contract reward is not primary production but cleaning out back generation inventory. Hard to say at what price is traditionally a customer freebie and cost to Intel.

On back generation surplus this analyst still sees Intel primary production volumes lower than other analysts perhaps counting in their estimates back generation Intel and OEM surplus in primary procurement and in quarter OEM unit volume end sales estimates.

One thing's for certain pursuant Intel q2 financial call, no financial analyst brought up Xeon inventory digestion where this analyst estimates there's sufficient Xeon Skylake and Cascade Lake channel inventory to satisfy the majority of uses on known product for the next three to four years. XSL/XCL+r at 400 M units produced where 60% is 4-way capable.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing