Any company that holds more than a quarter of a market – by money or shipments – is doing pretty well. Those few that have somewhere between a third and half of the market are exceptional. Those that attain 65 percent are rare indeed. And those that have 85 percent or more of their market are probably wielding monopoly power, whether they want to or not, and probably also should be regulated if they are in a key industry for the economy.

Monopolies don’t need to be broken, they just need to be watched and counterbalanced as necessary for the good of consumers and to foster at least some competition. Near monopolies need to be watched as well, but in the IT sector at least, the marketplace of ideas and ambition usually takes care of the problem, with upstarts taking on incumbents to try to siphon off their revenues and profits. This can be hard, as AMD has found out twice now – first with the Opteron processors and now with the Epyc processors nearly a decade later – when trying to take on Intel in datacenter compute, for instance. Oracle in relational databases seemed unassailable for a long time, but no fortress with its moats holds forever. Ditto for datacenter switching and routing giant Cisco Systems, which had Juniper Networks come after it in routing and then in switching. But for datacenter switching, particularly at the high end with hyperscalers, cloud builders, other service providers and telcos, and some large enterprises, it is Arista Networks that has been dogging Cisco’s heels relentlessly, thanks in large part to very good merchant switch ASICs that started coming to market more than a decade ago – particularly from Fulcrum Microsystems (long since part of Intel) and Broadcom initially, but now including Barefoot Networks (now also part of Intel), and Innovium (still freestanding and selling its ASICs to Cisco and others, and XPliant (now part of Marvell by way of its acquisition of Cavium). Oddly enough, Arista Networks has not done deals with Mellanox Technologies (now part of Nvidia), but that could change.

It is with all of this in mind that we consider how Arista Networks is doing as we are in the midst of the Great Infection and the resulting medically induced global recession. Serial entrepreneurs Andy Bechtolsheim and David Cheriton, who founded Arista Networks quietly in late 2004 with Ken Duda and uncloaked the company in 2009 with former Cisco switching top executive Jayshree Ullal, who has been the company’s president and chief executive officer since October 2008, when the Great Recession was really building momentum and it was clear that both servers and switching in the datacenter were ripe for change. These Arista Networks executives have a long history, sometimes together, in networking and distributed systems, and we talked about this in detail a few years ago and are not about to repeat all of that history now.

What is relevant today is that Arista Networks has done what seemed to be impossible: Actually take on Cisco in its switching bastion in the high end of the datacenter and win customers, revenue, and profits. Arista Networks has more than 6,000 customers today, and has taken an appreciable bite out of Cisco, and this implies that others can do so as well, and the very people who helped transform Cisco from a supplier of Internet routers to a maker of datacenter switches are the ones who are picking Cisco apart. (Ullal came to Cisco in 1993 when Cisco bought Crescendo Communications for its 100 Mb/sec switches, and Cisco bought Granite Systems, a maker of 1 Gb/sec switches founded by Bechtolsheim and Cheriton three years later – and only one year after it was founded. When Arista Networks uncloaked back in 2009, more than a few people expected that Cisco would snap it up and embrace merchant silicon, but instead Cisco went down its Nexus route with proprietary ASICs and dug in for a protracted battle. In recent years, Cisco has adopted merchant silicon – we did a deep dive on its chip choices in the Nexus lineup here – becoming a little more like Arista Networks. And the two got into a protracted legal battle which they settled in the second quarter of 2018, with Arista Networks paying Cisco $405 million, and now they are fighting it out in the markets instead of in the courts.

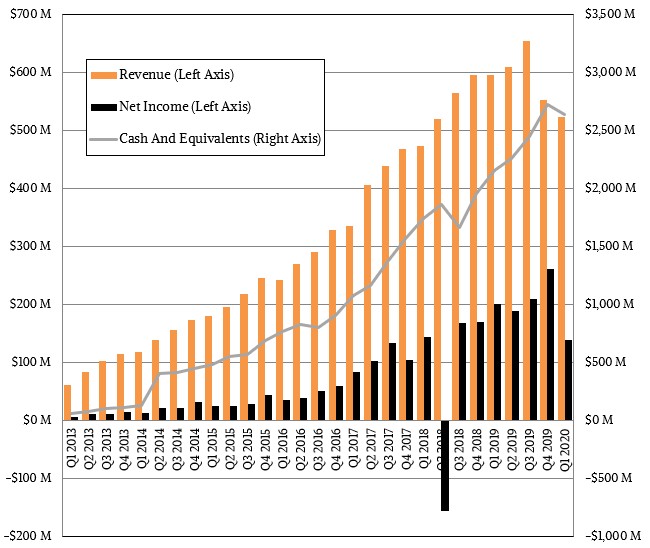

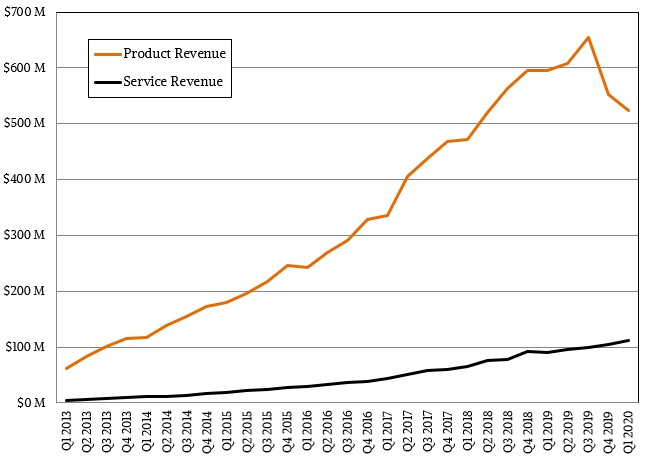

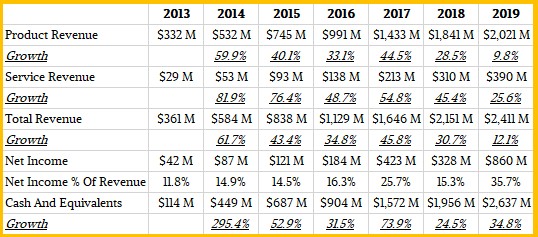

Arista Networks has been growing more or less steadily since its inception, and we have data going back to 2013 because the company went public in 2014 and backcast that far ahead of its initial public offering. But clearly, as the server market was booking in the fourth quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020, at least as far as the numbers we have seen so far indicate, something was going on in datacenter switching – and that something was at least caused in part by disruptions in the supply chain for Arista Networks in the first quarter of this year due to the coronavirus outbreak. In the quarter ended in March, product revenues were off 18.7 percent to $410.9 million, but services revenues, which are largely insulated from sudden downturns, rose by 24.6 percent to $112.1 million. Add it up, and overall revenues fell by 12.2 percent to $523 million flat, and net income fell by 31.1 percent to $138.4 million. Arista Networks had $2.64 billion in the bank, which is over a year’s worth of revenue as cash, and this does not include another $596.8 million in deferred revenue. So it is in great financial shape to weather the coronavirus storm in that regard and in a world where cash is king, queen, and jack.

Given the capriciousness of its hyperscaler and cloud builder customers, you almost have to look at Arista Networks on an annual basis instead of a quarterly one, and you have to take a long view on the company, just as we always advised companies to do when looking at HPC businesses such as those from Cray and SGI, both of which were absorbed by Hewlett Packard Enterprise in recent years. If you look at Arista Networks over a seven-year span, here is what it looks like:

On the call with Wall Street analysts going over the numbers for the first quarter, Ullal said point blank that Arista Networks was not able to predict revenues for the full 2020 year, but said that the company would be dialing back expenses to levels set in 2018 so it would not be unpleasantly surprised. The company did give guidance on revenues for the second quarter, saying that they would be somewhere between $520 million and $540 million, up 1.3 percent to 5.2 percent with the midpoint of $530 million being up 5.3 percent year on year. Some of that is business sloshing over from the first quarter into the second quarter, of course.

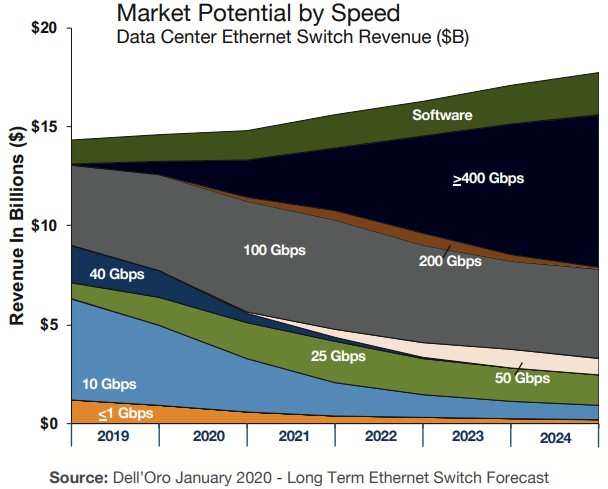

There are some other changes going on in the market, and one of them is that the ramp of 400 Gb/sec Ethernet is being delayed at some customers who might otherwise have been a little more enthusiastic about getting on the front end of that transaction.

“It is not so much that we are seeing a change in product mix,” explained Ullal. “I would say the biggest change we are seeing is people are doubling down on 100 Gb/sec and 400 Gb/sec is getting pushed out to next year in the cloud.”

Not that anyone was expecting a big ramp of 400 Gb/sec Ethernet this year, although Arista Networks has had products rolled out since October 2018 to attack this upper echelon. Ullal said that during the quarter, various market researchers indicated that around 5,000 ports of 400 Gb/sec equipment were sold and for 100 Gb/sec equipment, several million ports – actually, 3.5 million ports according to Dell’Oro – were sold. “So there is a 1,000X magnitude difference between the two, and I don’t think that is going to change in the near term,” she said, adding that Arista Networks always figured 400 Gb/sec trials would get going in earnest in the late 2020 timeframe as the cost of 400 Gb/sec optics came down, with deployments in 2021. The 400 Gb/sec ramp is really as much about increasing the radix and port density of switches as it is in getting more bandwidth into each port, and Bechtolsheim has been clear about this from the beginning and reiterated it at our Next I/O Platform event last summer. And both Bechtolsheim and Ullal have been clear that this is not 100 Gb/sec or 400 Gb/sec, but a combination of the two at most companies.

Here is the target market that Arista Networks, Cisco, and the switch market is chasing:

As you can see, there is still going to be a lot of 10 Gb/sec Ethernet revenue in the datacenter in 2020 and 2021, and even 40 Gb/sec is going to have a last hurrah this year it looks like, according to the forecast from Dell’Oro that was done in January of this year. It is going to take a long time for 400 Gb/sec and even 800 Gb/sec Ethernet to get rolling.

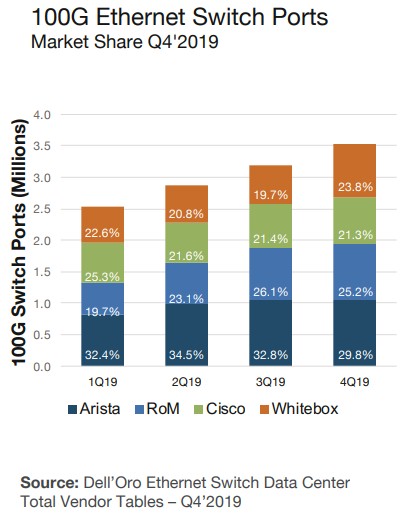

In the belly of the 100 Gb/sec transition, Arista Networks has done well. Here are the port counts by quarter sold worldwide, with the revenue share from Cisco, Arista Networks, the whitebox switch makers, and the rest of the market:

Arista is averaging somewhere near a third of the total capacity of 100 Gb/sec ports sold, and Cisco is under a quarter and heading towards a fifth of the market. This is amazing, really, and it shows the port of the merchant ASICs that came into being and the power of a non-proprietary hardware platform (meaning the switch vendor itself doesn’t control it) that is akin to X86 running Linux in a world that was dominated by dozens of RISC chips all running their own variants of Unix. (The analogy is not perfect, but it is close between servers twenty years ago and switches starting ten years ago.)

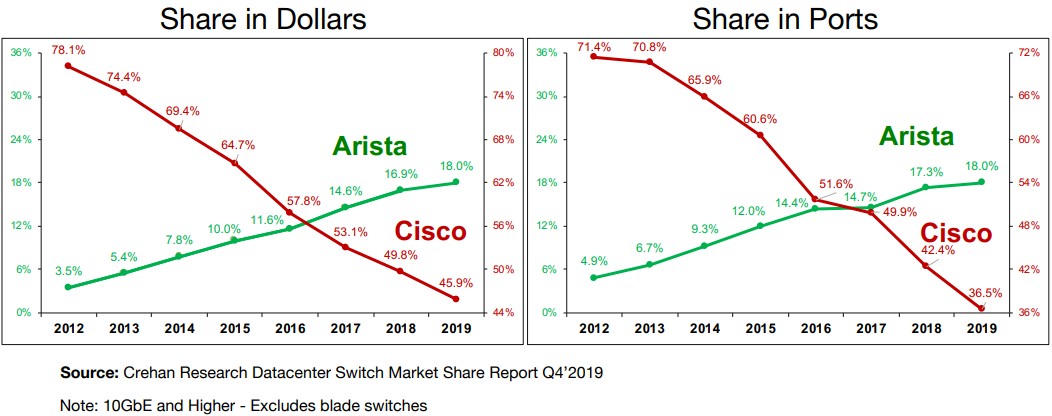

This chart, which comes from Crehan Research, really brings home the dramatic impact that Arista Networks – and indeed, whitebox switch makers, too – has had on the formerly dominant revenue and port share that Cisco enjoyed for many years.

But starting with the 10 Gb/sec generation and moving forward, Cisco let vendors – particularly Arista Networks – get a beachhead in the datacenter and now they are taking big pieces of the glasshouse and opening new fronts in campus networking and, with the acquisition of Big Switch Networks in February, software defined networking.

That last bit is very interesting, and something we are going to talk to Arista Networks about. Stay tuned.

In the interim, we think that customers are going to look at the cost per bit for networking gear very closely, balancing out high radix and high port count against lower bandwidth and potentially much lower cost per bit. A switch ASIC with 3.2 Tb/sec or 64 Tb/sec of aggregate switching bandwidth might have a street price cost per bit for a 25 Gb/sec server port from the top of rack that rivals what could be delivered with a 12.8 Tb/sec or 25.6 Tb/sec device, which would very likely deliver 50 Gb/sec or 100 Gb/sec down to the server. It all comes down to how flat companies want to make their networks and how fast they want their server port speed to be. Flatter networks are cheaper by far because they have fewer switches in the infrastructure, but it might have a higher capital outlay per server (not per bit) and cash right now might be more important than buying server bandwidth for the future. We shall see how this all plays out, but a server boom should mean a networking boom – right up to the moment it doesn’t if this recession really goes deep and wide.

Be the first to comment