Intel has made another big move toward its ambition to dominate the artificial intelligence space in the datacenter, acquiring Israeli AI chipmaker Habana Labs for $2 billion. The amount dwarfs the $350 million or more Intel paid for AI chipmaker Nervana Systems back in 2016. Which leads us to the question: Why would the company buy a startup that offers products that directly compete with the Intel’s recently launched Nervana-based Neural Network Processor (NNP) line?

First a little historical context. Habana was one of the first AI chip startups to make its silicon available to datacenter customers. Goya, the inference chip, was released in January 2018, followed by Gaudi, the training processor, in June 2019. The Gaudi training chip is currently sampling with unnamed hyperscale customers. Goya is also being trialed by a number of select customers. And considering that Facebook’s Glow compiler has been ported to the platform, we have a pretty good idea who one of them is.

Habana’s aggressive roadmap beat even Intel to the market with its NNP-I and NNP-T processors, the chipmaker’s two corresponding offerings for inference and training, respectively. At Intel’s AI Summit in November, Naveen Rao, corporate vice president and general manager of the company’s Artificial Intelligence Products Group, launched the two NNP product sets, announcing Baidu and Facebook as early customers.

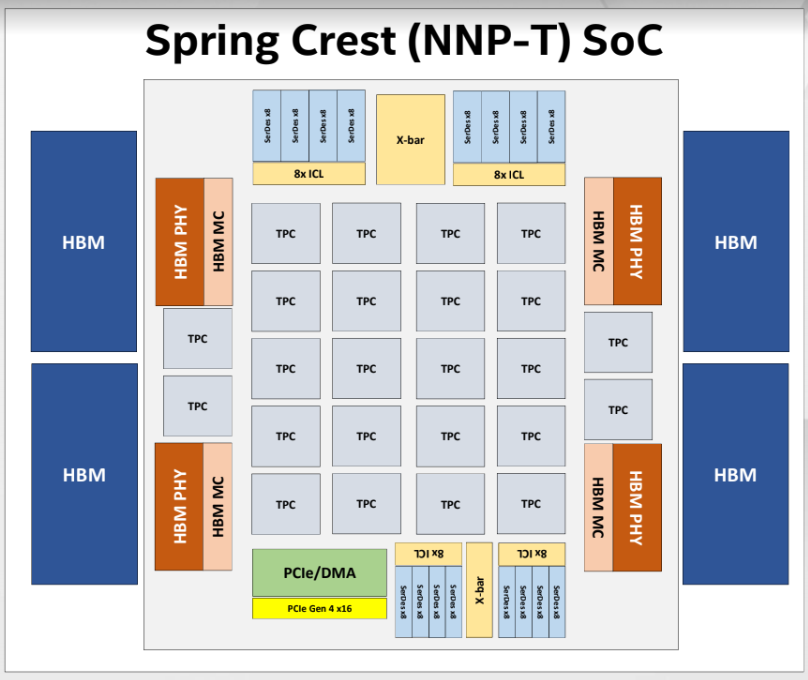

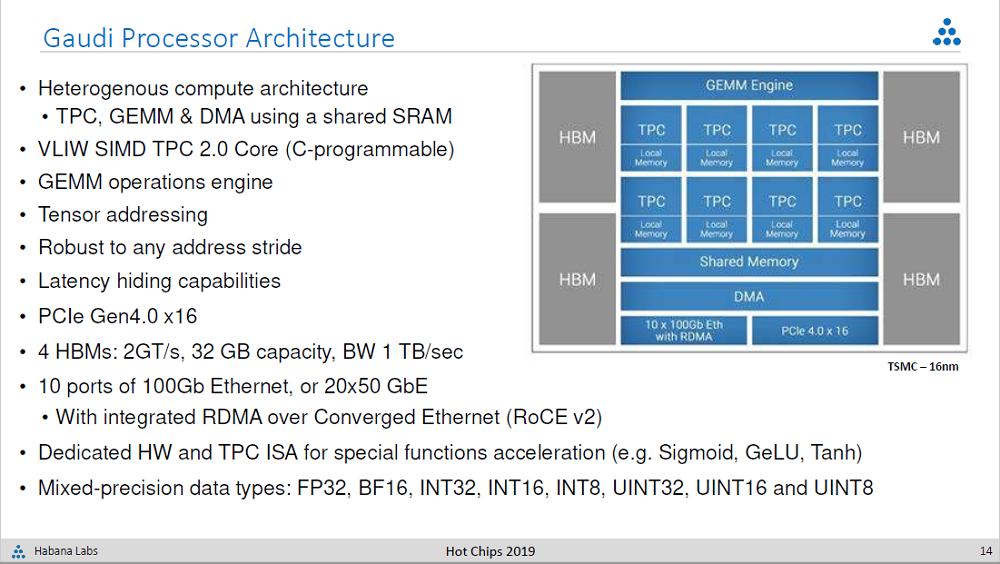

The similarities between Gaudi and NNP-T are especially striking. Both are powered by tensor processing units sharing SRAM memory and hooked up to 32 GB of on-package High Bandwidth Memory (HBM). Both incorporate built-in networking to support scale-out configurations: NNP-T uses a custom network; Gaudi employs standard RDMA over Converged Ethernet (RoCE). The schematics below illustrate the similar designs.

Here’s the Intel chip:

And here is the Habana Labs Gaudi architectural block diagram:

When asked about what Intel has planned regarding the overlapped products, they were non-committal. “We’re not making roadmap decisions on day one,” offered the spokesperson. “We’ll take time to assess this combination with input from our customers.”

Make no mistake. Intel wouldn’t be plunking down $2 billion if it was completely satisfied with its Nervana-based strategy. There is not enough daylight between the Habana offerings and the NNP products to justify both portfolios. So that means either the products will be merged somehow, or one line will be jettisoned in favor of the other. And since they just bought Habana, it’s difficult to imagine that it spent so much money just to give customers a different set of tires to kick.

Some of us at The Next Platform – TPM in particular – believe that this Habana deal is as much about keeping Habana out of enemy hands as it is about adding technology to the Intel portfolio.

We will take Intel at its word that it is not going to rush to any decisions right now. Dropping NNP immediately would give Baidu, Facebook, and whatever other customers may be surreptitiously trialing the hardware severe whiplash. At the very least, Intel would port the AI software stack – the Deep Neural Network Library (DNNL), along with the associated machine learning frameworks and libraries – to the Habana hardware to easy any needed transition.

Given the rapid pace of AI hardware development, what eventually emerges may be an evolved hybrid of the two product sets. Imagine an NNP-T offering, incorporating the standard RoCE networking of the Gaudi design. Or consider lower-wattage Goya products, offered in M.2 or PCI-Express form factors, as is the case for the NNP-I line.

There are certainly other ways Intel can make the Habana Gaudi and Goya technology more attractive. Just the fact that Intel has the size and the developer base necessary to maintain a complete AI software stack for their hardware should give customers more confidence that their applications will continue to run even as that hardware morphs over time. For most customers, that’s at least as important as any temporary performance advantage afforded by one technology over another

Intel can also surround its AI hardware with other in-house technologies like its Optane DC persistent memory and Barefoot Networks switching, creating additional differentiation for those products. Plus, the fact that Intel designs and manufactures chips for a living should give those same customers at least some assurance that those products can be maintained on a competitive roadmap. We same “at least some” because Intel is only to happy to discard product lines they deem no longer worthy, for example, Itanium, Larrabee/Xeon Phi, Omni-Path, and so on.

Even taking Intel’s propensity to drop product lines into consideration, when all is said and done, a multinational behemoth is perceived as a less risky proposition by hyperscalers and enterprise companies alike compared to a small startup out of Israel. (We could argue that it guarantees very little. Ask QLogic InfiniBand customers, for instance.)

If $2 billion seems like a high price to pay for what is essentially Intel’s third shot at the AI datacenter business, keep in mind that the chipmaker expects AI processor revenue to be greater than $25 billion by 2024, $10 billion of which will apply to the datacenter market. And those number just go up in succeeding years. Given the youth of the market for AI silicon and the fast-moving nature of the technology, it truly is anyone’s game right now. And if Intel has been consistent at anything in this space, it is that it is not shy about placing some big bets.

Be the first to comment