It has been nearly five years since Michael Dell lined up $24 billion in cash to take the IT company that bears his name private, and it has been nearly four years since Dell announced its mammoth $67 billion deal to acquire enterprise storage maker EMC and its server virtualization minion, VMware. The deal to acquire both EMC and VMware closed three years ago this week, and it cost $7 billion less than expected, and we figured now might be a good time to take a look at how Dell is doing in its strategy, which involved selling off some troublesome services business and stopping trying to be the old IBM.

Dell is taking a radically different tack from its main competitor, the spinoffs from the former Hewlett Packard. Hewlett Packard split into two companies – one focused on the datacenter that sold off its services businesses as well as its software business, and another that sells PCs and printers. The idea was to bring greater focus so the individual baby HPs – that would be Hewlett Packard Enterprise and HP Inc, and we suspect there is a pun lurking in there consider the profits the latter piece of HP gets from selling containers of printer ink – would do better in their respective markets. We think that HPE lost some of its leverage with parts suppliers thanks to the breakup and has been burned by high component costs in recent years, and the financial evidence suggests that HPE has not been able to fully defend against the encroachments of a host of aggressive OEMs and even more aggressive ODMs that are trying to steal its server and storage business away.

Dell has been particularly aggressive in the enterprise and with hyperscalers and cloud builders, and has eaten market share away from HPE while the latter company has backed away from that so-called “Tier 1 service provider” business that it was craving when it launched its Cloudline servers in conjunction with Foxconn several years ago. HPE, being a public company, has to focus on profits and growth, and Dell, being a private company still (with the exception of VMware, which is 80 percent controlled by the company with the other 20 percent still in the hands of Wall Street) can do whatever it wants for the long haul of gaining market share with datacenter infrastructure as it sees fit. Still, Dell behaves a bit like a public company these days, even though it doesn’t have to, by showing Wall Street some of its financials above and beyond the figures that VMware puts out each quarter since it is still publicly held. At some point, Dell could go public again as is rumored, either by a direct sale of shares to Wall Street or through VMware by stuffing a $90 billion company into a $9 billion bag and then changing the name of VMware to Dell.

While that is all interesting, what really matters is what Dell is doing compared to its datacenter peers and how well or poorly it is faring in its desire to gain market share and influence in the glass house. Two years ago, in the wake of the acquisition of EMC and VMware, we did a detailed financial and strategic analysis of Dell up to that point, and we are not going to repeat all of that here. We are going to look at Dell from just before the deal went down and up until its second quarter of fiscal 2019, which ended in early August, and using the characterizations it currently has when it talks to Wall Street. Dell no longer has a services or software group, just like HPE doesn’t, but it still has a PC business that is largely a commercial operation and that gets its foot in the door at millions of companies worldwide. And, importantly, that gives Dell leverage with suppliers of processors, memory, storage, and other parts it uses to assemble its machinery.

Here is the main take away. If you go back to that original analysis from two years ago, it is immediately obvious that Dell reached its goal of generating $60 billion in revenues in fiscal 2011 and early 2012, but it could not hold the line and therefore it went private so it could pare down and then take a run at EMC and VMware to get a better configuration that was more suited to the times. It cost a lot – $84 billion, or around a year’s worth of revenue as it is currently running – but both Dells, meaning the company and the man, have no regrets about spending other people’s money (and some of the founder’s cash) to get the freedom of movement that being private affords.

King Of Servers

As the latest market statistics from IDC point out, Dell has done a great job eating market share from HPE while at the same time keeping the ODMs and the OEMs that have ODM-like units at bay in the server arena. Dell has been the shipment leader in servers for the past four quarters, and has had seven consecutive quarters of server sales growth to finally break through to become the top revenue generator in the server racket in the world. This is quite an accomplishment, considering the nature of the competition.

In the second quarter (calendar, not fiscal), IDC reckons that Dell’s server revenues grew by an astounding 52.9 percent to $4.25 billion and its shipments rose by 16.6 percent to 574,600 units. Just to give you a sense of scale, back in the early dot-com boom, circa 1997, all vendors combined pushed around 500,000 machines per quarter, and we thought that was a lot. Dell had $900 million in X86 server sales in 1997, according to IDC, and the next year it got very aggressive and nearly doubled its server sales to $1.6 billion while the combination of HP and Compaq (which did not merge until 2001) grew by 6 percent to $5.5 billion. Dell has been chasing the ProLiants with its PowerEdge iron for a very long time. And it has finally caught and passed them, and it did so not by giving up PCs and by staying in the hyperscale and cloud builder racket as best it can, considering the intensity of the competition. HPE, by contrast, grew server revenues by 11.7 percent to $3.74 billion and server shipments fell by 12.4 percent to 443,700 units. That is a pretty big gap in both sales and shipments, and it is not clear how HPE will close that gap, or even if it wants to.

Had Dell not gone private, it could not have come to this dominant position. The question we have is whether this market share gain will lead to more profits down the road for Dell, which is what this is really all about. It may not, but it could. What we can tell you for sure is that Dell has, like many IT suppliers selling raw infrastructure, had trouble making big money even though it generated big revenue. This was true before it went private and bought EMC/VMware, and it is true today, too.

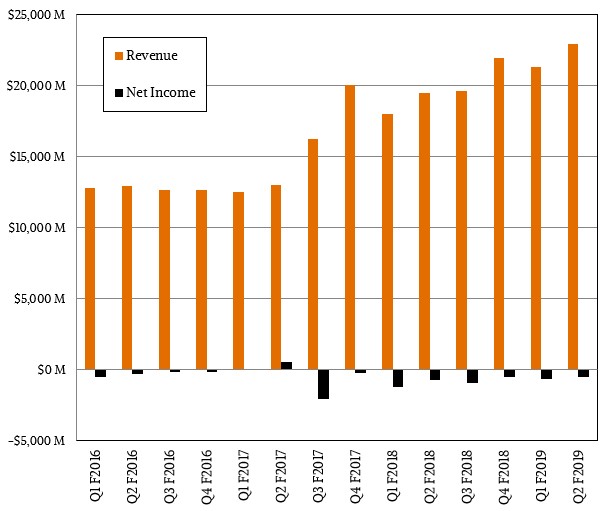

The revenues have gotten a lot taller thanks to the addition of EMC and VMware, despite the selloff of its services and software arms, and in fact, Dell’s run rate is now closer to $90 billion a year, not the $60 billion a year that was its goal for many years.

But the profit bars, despite the underlying operating margins that the company brings in, have been mostly negative for the past three and a half years. This is something that Dell, the man, knew would happen and got permission to engage in from his many bankers and Silver Lake Partners, the equity firm that helped do the leveraged buyout and the acquisition of EMC and VMware.

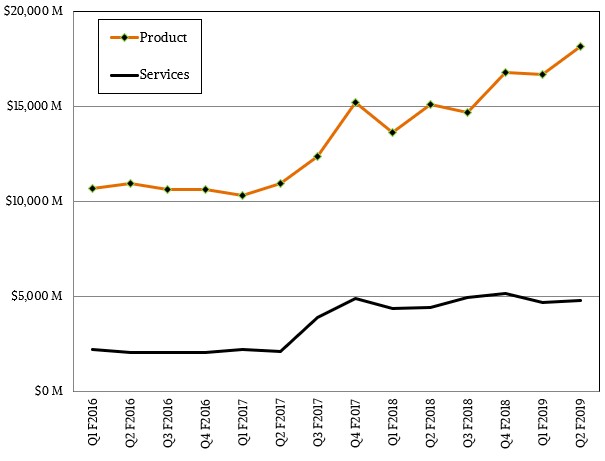

The new Dell has ramped up a fairly steady break-fix, warranty, and support services business for its products, which just hums along at around $5 billion per quarter now, and is a lot less stressful (and human intensive) than the outsourcing and systems integration services that Dell offered after it bought Perot Systems many years ago. The company’s product sales bumped along at around $10 billion a quarter before the EMC/VMware deal, but since then have been on the rise at a pretty steep angle not only because of those deals, but because Dell has increased its share of the server and PC business through very aggressive market segmentation and execution. Through various acquisitions and some organic growth, Dell’s storage business has grown by a factor of 8X, and its server business is now about 60 percent larger, but we think about half of that growth is coming from richer configurations as well as higher memory and flash prices, with the remainder being the expansion in shipments.

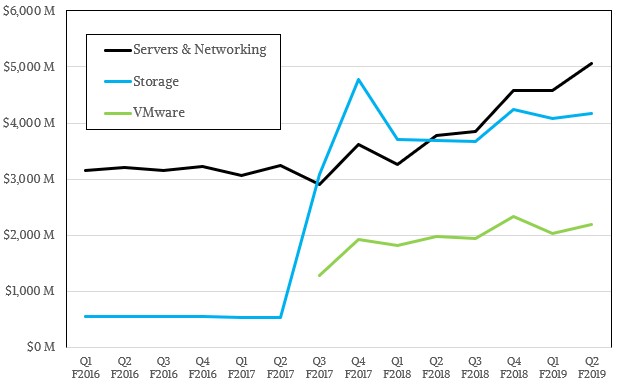

In the quarter just ended, Dell sold $5.06 billion in servers and switches, up 34 percent year on year, and damned near all of that has to be servers despite the very good switches that Dell makes (thanks to its Force10 acquisition way back in the summer of 2011). It is not clear how much of the server revenues came from hyperscalers and cloud builders, who have high volumes but contribute we presume are very skinny margins or none at all, and how much came from enterprises, who are where the profits still come from because they buy generic machines with management controllers and hardware redundancy because a lot of machines are running just one application, or one set of small applications, rather than being spread over a cluster. The server revenues are, as we have said, being pushed up by higher component prices and richer configurations, but whether this means better margins for Dell is a real question. Maybe not. A stable pricing environment where the cost of components comes down predictably always plays better to supply chain jockeys like Dell.

The Dell storage business has been obviously significantly enhanced by the addition of EMC and, to a certain extent VMware, but VMware’s virtual SAN business is not counted as storage. (Just like its virtual servers and virtual networking do not end up in the Server & Networking line of business.) It is getting increasingly difficult to draw lines between what is a server, a switch or storage, so what we can do is take a gander at how the Infrastructure Services Group as a whole is doing. Within this, storage revenues rose by 13 percent – still faster than the market for enterprise storage as a whole, we think – to $4.17 billion. Interestingly, if you peel out some networking from the server number above, Dell’s server and storage businesses are roughly the same size. This is not at all consistent with the market at large, where enterprise storage spending was $13.2 billion in calendar Q2 (up 21.3 percent) against 111.8 exabytes of total capacity (up 70.7 percent), but server spending in the same period, according to IDC, rose by 43.7 percent to $22.53 billion. Here’s the fun bit. If you add that all up, the Infrastructure Services Group had $9.23 billion in sales, up 24 percent year on year, for Dell’s fiscal Q2 and operating income was up 56 percent to just a little over $1 billion. That’s 11 percent flat of revenues, which is not too bad for a hardware maker.

But the trouble is that Dell, overall, continues to lose money. Well, that would be troublesome if Dell was public. As long as Dell pays back its relative handful of investors with their principle plus interest, this is a lot less troublesome than making millions of cranky shareholders who do not understand the IT business happy. Over the span of time we have examined in the charts above, from Q1 of fiscal 2016 through Q2 fiscal 2019, the server and networking business has grown by 1.6X, but storage has grown 7.6X and that has made Infrastructure Services Group expand revenues by 2.5X and operating margins to rise faster at 4.2X. If Dell maybe breaks $12 billion in sales for datacenter hardware, this part of the business could collectively have a real profit.

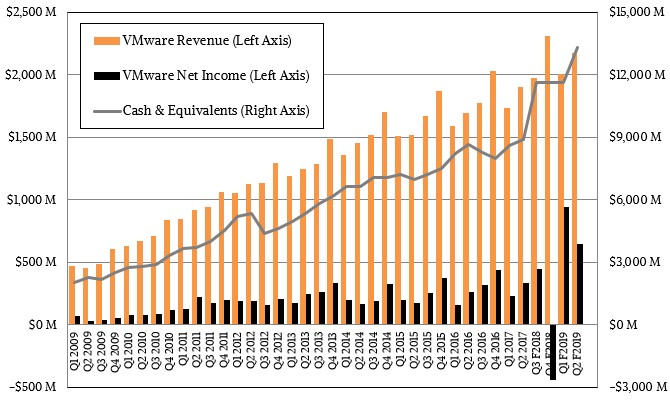

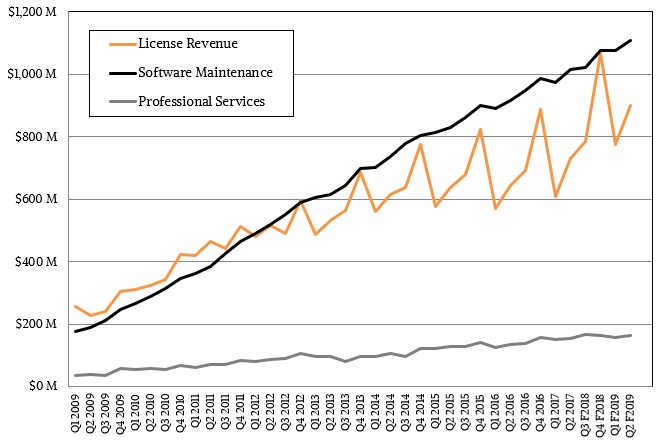

If Dell wanted to make its datacenter infrastructure business look instantly profitable, it would merge VMware into the Infrastructure Services Group. VMware is three times as profitable at an operating level as the core Dell infrastructure business, bringing 33.5 percent to the middle line. In the second fiscal quarter, VMware had $2.19 billion in revenues and an operating profit of $736 million, and brought $644 million of that to the bottom line. That is another way of saying that without VMware, Dell plus EMC would have lost about $1.1 billion against $20.75 billion in sales. Dell is clearly trying to do two things: make it up in volume with the core datacenter hardware and push towards breakeven and then grow VMware enough to actually make some money over the whole enchilada. This is not trivial since sales of VMware’s vSAN virtual storage eat into EMC’s actual SAN sales, and NSX similarly eats into switch sales. The point is, over time, as storage and networking virtualize more, this should boost the server business and eat into the storage and switch businesses, perhaps enough to get Dell’s proportion of servers and storage more inline at a 2:1 ratio as the industry at large is. (Storage in a cluster usually does not cost as much as compute, and networking can’t be more than 20 percent of the cost or organizations freak out.)

VMware presents an interesting set of challenges as well as rewards. With over 500,000 customers worldwide and probably all but a few hundred hyperscalers and cloud builders and a few thousand HPC centers not using its wares across maybe the top 50,000 IT sites worldwide, this is excellent market penetration and it is hard to imagine increasing this base. A certain number of companies are going to use the entire Microsoft Windows Server stack or the entire Red Hat Enterprise Linux stack, and that is all there is too it. So they won’t need VMware. Those who have encapsulated their applications in ESXi virtual machine wrappers are not going to be inclined to move them any time soon.

The question we have is what happens when and if Dell actually takes full control of VMware, or goes public again by pulling itself into VMware and dropping the entire value of the company into VMware and then changing its name to Dell. (There has been such talk for years now.) We think Dell, the man, doesn’t want to be the chairman and chief executive of a public company so much as he wants to run an influential company that is at the top of its game and at the top of the class. But VMware can’t afford to alienate the other four out of five server makers in the world that are not Dell if it wants VMware to continue to grow. Owning VMware might be as difficult as not owning it, if the competitive pressures shift if server makers start pushing other virtualization or container stacks.

Dell is ramping up its leasing and flexible metered pricing on datacenter hardware (more on that in a second), and probably needs to shift from perpetual licensing and annual support contracts to a true subscription model for VMware at some point and get off the upgrade cycle mill for VMware stuff. One key idea with the Dell-EMC-VMware merger was to get some annuity-like businesses for infrastructure, much as IBM has been able to do with leasing and monthly software licensing on its venerable System z mainframe platform.

The enterprise server virtualization juggernaut has doubled its revenues in five years, but its profitability (at the net, not operating, level) has been inconsistent. But not bad, mind you. VMware’s $13.3 billion in cash, most of which it made the hard way by earning it, represents 62 percent of the total cash hoard the company has.

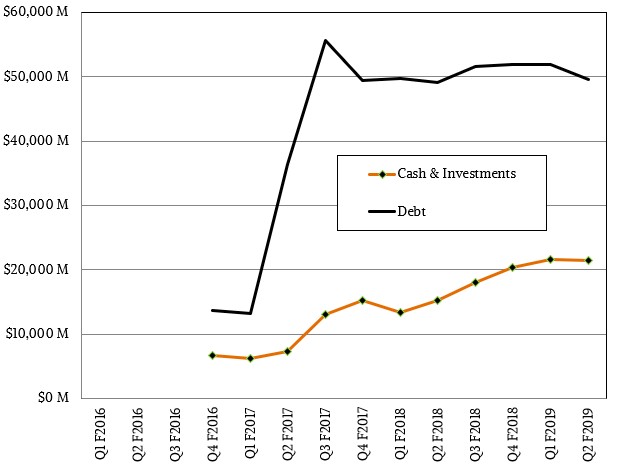

The cash pile is not growing as fast as it was, but part of that is because since the announcement of the privatization deal and then the EMC-VMware deal, Dell has paid off $13.7 billion in core debt to its banking and private investors. The debt load shot up thanks to those deals, and has been hovering around $50 billion, and you might be thinking, what gives? Some of that debt – and an increasingly large part – is the value of leases and other kinds of flexible financing and metered usage payments that Dell is increasingly selling as part of deals with large enterprise customers who are tired of laying out capital. They want their IT supplier to do it so they can get a more cloud-like experience.

This push to metered pricing will have the effect of balancing out the revenue streams and profit pools at Dell. Or at least that is the idea.

Be the first to comment