By its very nature, HPC isn’t exactly cheap to do. Even moderate sized systems ring in at many hundreds of thousands of dollars. Get serious about HPC, and it quickly becomes a multiple hundred million dollar – and therefore cost prohibitive – affair.

Since the very first computing machines were constructed, we have sought out ever more intricate ways to slice them up and share them out, including modern advanced job schedulers and containerized systems. This is all well and good for folks in academic centers, or those with substantial budgets, but what happens if you fall into the large mass of small or medium sized businesses who need access to HPC but aren’t able to get started because of a lack of the needed skills, money, or physical resources?

Even towards the higher end of the business spectrum you still may not have enough physical capital to invest in large capacity of equipment, it quite simply just may not be able to pay for itself at the final bottom line. Also, the physical equipment is only half the battle. Never mind all the complicated plumbing and power provisioning gymnastics you have to do before you can even plug anything in, you will also need some expert humans to actually make it all work. These humans are specialized, difficult to find hire and retain, and have unique skill sets. It would make significantly more financial sense to rent the humans along with your computing capabilities by the hour. To make the analogy, very few residential homes own their own landscaping equipment; it is just far cheaper and much more sensible to rent the expert humans and their equipment by the hour.

Industry programs for HPC aren’t new ideas, and for decades public and private collaborations between academia and industry have thrived, each adding value with money flowing from industry into higher education, and profit generated by the industrial partners through novel products and services. It is essentially a chocolate and peanut butter solution – they do just go so nicely together. However, building partnerships to supply highly specific, technical services to industry as a physical product from inside academic organizations is non trivial.

The pace, velocity, and style of these two classes of organizations do unfortunately have an obvious impedance mismatch. Especially when the end game is to supply advanced computational technology and support that can significantly impact the bottom line of a company and shareholders. The shape, size, and level of detail that specific organizational interactions take will also need to vary considerably, accordingly we are going to call out four projects, a regional, a European, a national, and finally a smaller detailed local project. Each describe how industry, academia, and supercomputing centers have come together to improve their science, research, and product development.

The Regional Project

An interesting high level interaction of private industry (Cisco Systems and EMC), with state and local government in the Massachusetts area with higher education leaders MIT, Boston University, Harvard University, Northeastern University, and the University of Massachusetts resulted in the physical construction of the highly successful Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Center. The only slight drawback in designing such centers with a vast array of a committee of experts and organizations is that it will inevitably result in you naming your high technology research datacenter the MGHPCC. Catchy, right?

However, the important point here is that not only did private industry and academia have to come together to construct the center, they had to continue to innovate within and externally to it. It is not just the bricks and mortar. The MGHPCC has continued to build stronger ties to industry, with The Commonwealth Computational Cloud for Data Driven Biology (C3DDB) as an example of one of the earliest projects funded by the Massachusetts Life Science Center to engage the datacenter with local companies. The MGHPCC now lists out a number of collaborative projects including a regional large shared storage project and also a wide reaching statewide open cloud project to share compute and resources. The MGHPCC is an example of nucleating industry activities around a core set of academic projects connected through a hub which started simply as a regional datacenter that now helps to meet the needs of a whole raft of industrial collaborations.

The European Project

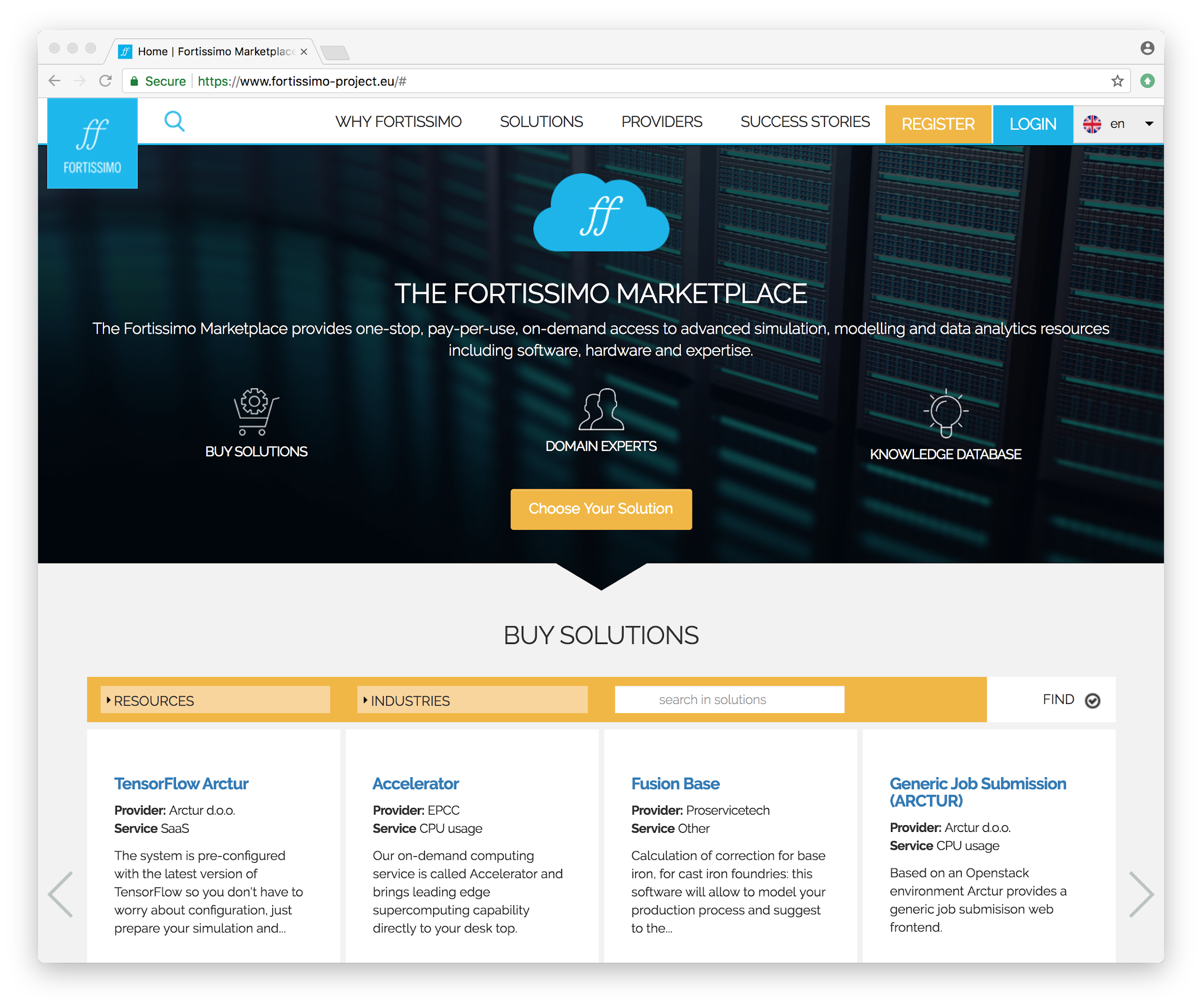

In Europe, they have a particularly elegant approach (certainly winning the collaborative project name contest if nothing else) to the issue of interacting with academia and industry. The Fortissimo project received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development, and demonstration and is coordinated by the University of Edinburgh and 123 partners. It is an extremely large operation (123 partners) if not only in budget required but also in terms of the pure organizational dexterity needed to be able to pull it all off.

At the recent ISC industry day, Mark Parsons of the EU Fortissimo Project explained: “HPC is an immensely powerful tool to improve products and services across many industry sectors. It’s also expensive and complex to use the first time a company decides to adopt it.” To that end, they formed the Fortissimo Project, which has now helped almost 100 manufacturing SMEs in Europe to take their first steps with HPC. Parsons discussed a number of success stories from simulation of high-temperature superconducting cables, additive manufacturing and steel casting and also highlighted a project with Koenigsegg AB (they manufacture extremely fast motor vehicles) who managed to save over €100,000 every year in design costs by partnering with the folks at the Fortissimo marketplace. Like the MGHPCC story, it is both compelling and fascinating to see these subtle interactions result in real world development of new products and processes.

The National Project

The United States also has a successful program that runs out of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Called NCSA Industry, the program has worked with more than one-third of the Fortune 50 companies, in sectors such as manufacturing, oil and gas, finance, retail and wholesale, biomedical, life sciences, and agriculture.

To do this, NCSA has what appears to be a two pronged approach from a technology point of view. First, it has an up-to-date, dedicated computing environment called iForge that is refreshed frequently and sits inside the 88,000 square feet NCSA datacenter. This system gives NCSA the ability to provide computational access to small and medium enterprises and provide effectively a computational on ramp. If that doesn’t scale for you, NCSA Industry can bring out the big guns and will offer up allocations on their mighty Blue Waters system. It is no surprise that this makes the program that currently includes 35 industrial partners as one of the largest industrial HPC outreach programs in the world.

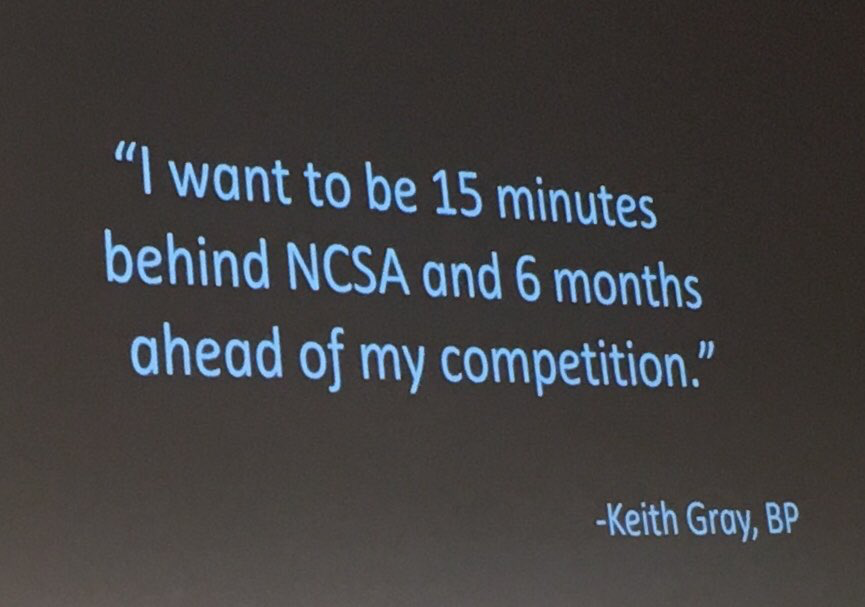

As an example, NCSA in partnership with ExxonMobil recently took a reservoir simulation for oil and gas scaling, and after a planned maintenance of the system, they were able to “borrow” the entire system, where they not only showed strong scaling of their algorithm but were also able to allocate 716,800 MPI processes. This run set a new world record for an oil and gas simulation. ExxonMobil stated the simulation could result in $1 billion in indirect return on investment. That is a shockingly large ROI, but then again the machine and staff that were needed to run the simulation are equally impressive. Interestingly, Keith Gray of BP, who works in the same sector as ExxonMobil and also partners with the NCSA industry program, summed up their own interactions with NCSA and what it means to them perfectly in this quote shown by Brendan McGinty of NCSA, who presented the NCSA industry program ISC:

The Local Project

Heading back to Europe, and as homage to the fact that ISC is held in Germany, it was only appropriate that Steffen Hagmann, a PhD student at Porsche AG, spoke about the challenges of water management in the vehicle development process. Having water unexpectedly pour into your new $100,000+ luxury motor vehicle is quite obviously something that Hagmann (and Porsche AG) clearly wants to avoid inflicting upon their loyal customers. To do this they turned to HPC.

Hagmann has built the standard method for the numerical simulation of water management and uses it to make sure that Porsche AG keeps its cars and customers dry. He does this by weaving in the demands of his compute while the machines are not busy running regulated and important crash data suites of modeling. They turn to the High Performance Computing Center, or HLRS in Stuttgart, another center with a very catchy name. In any case, At the HLRS, Hagmann has access to a Cray XC40 with over 7.4 petaflops, the total Porsche AG workload is made up of 49 percent CFD structure computations and 47 percent crash predictions leaving about 4 percent left over of the allocation for Hagmann’s water models.

Porsche AG is considered a “partner” of the HLRS, the financial conditions for access were not disclosed, however Porsche are listed prominently on the HLRS website as a key partner. Some money obviously changes hands at the higher levels, but the important thing here is the leverage of the economies of scale and access to expert humans combined with high performance computing. For sophisticated users such as Hagmann, who has a well defined algorithm and simply needs access to more simulation time, this whole idea of a tightly coupled “rent-a-flop” model works out just fine.

Wrapping Up

Trying to understand the intersection of industry with high performance computing centers and resources was the high-level aim at the recent ISC Industry day. At The Next Platform, we see it as a series of efforts to remove barriers and reduce friction between industry and large HPC centers so they can seamlessly deliver computer time, storage and personnel expertise. As we continue to develop more complex AI and HPC applications and systems, it is even more important that our knowledge and best practice are able to be shared seamlessly between academic and industrial segments.

Some centers are simple “pay-as-you-go” computer rental operations, others with much more sophisticated agreements to work on multi-year deeply complex projects, and others more of a virtual hub or meeting place for exchange of ideas and sharing of knowledge. Whichever type of collaboration it is, the point is one of leverage, of being able to join forces on some of the world’s most difficult and challenging problems.

Coupling lots of extremely solid “shock and awe” science and overarching leadership who support and encourage the sharing of resources in a sustainable and secure fashion has been proven to lead to success. So, if you are in industry right now and you think you have a computing problem, and you can’t find help from anyone else, it is absolutely worth calling your local HPC center. From where we stand, and from what we have seen, they are all going to be very interested in hearing from you.

Be the first to comment