Designing and manufacturing processors – or paying a third party foundry to do some of the work – and then manufacturing systems and updating and modernizing operating systems and middleware is tough work. And it is work that few IT vendors and about the same number of hyperscalers do these days. Despite all of the gut-wrenching changes in the datacenter over the past six decades, International Business Machines is still in the game that it largely defined so long ago.

In the fourth quarter of 2017, the company’s System z mainframes had the highest shipment level, as gauged by aggregate MIPS computing capacity shipped, in the company’s history and despite the fact that there are maybe only 5,000 or 6,000 companies that still have mainframes deployed in the world, the aggregate installed base of MIPS capacity on Earth has grown by a factor of 2.5X since 2010. We don’t know the MIPS base number for the end of 2010, but we do know it was at 3.5 million aggregate MIPS in the first quarter of 2000 and just a tad over 11 million MIPS in the first quarter of 2007, when IBM had about 10,000 mainframe footprints. If you extrapolate that curve out – and it is slightly more exponential than linear, but only slightly – then there should be an installed base of mainframe MIPS of around 30 million or so in the world.

That is nearly a factor of 10X growth in the installed base of mainframe capacity in 18 years. That may not be Moore’s Law growth, but it is growth that is larger than that of global gross domestic product increase over that same time, and that is as good as it gets in transaction processing and the related activities that surround it. We suspect that at least half of that capacity is running Linux, which can honestly be said to have saved the mainframe.

The mainframe is not exactly the next platform, of course, but to its credit since its birth in April 1964, the mainframe has always been concerned with absorbing the technologies on whatever the next platforms are that are suitable for enterprise computing. And so the mainframe has evolved, and at a pace that the enterprises that depend upon mainframes can go with. The mainframe may be a dinosaur to some, but it is a colorful one with a fur coat that now gives birth to its young alive in a scaly pouch and that tends those babies in a way that is distinctly mammalian despite its core reptilian nature for security, sturdiness, and I/O weight.

The important thing about the mainframe, for those who are building the next platforms, is that the meaty profits that it brings to Big Blue in these early quarters of a mainframe upgrade cycle give it the money to invest in future z and Power processors and a steady stream of monthly licensing fees for operating systems, middleware, and databases that still gives the total mainframe stack gross margins that are probably well north of 80 percent of revenues. Those profits are what allowed IBM to develop the Power family of RISC processors in the first place and to take on Sun Microsystems, Hewlett Packard, and others in the open systems revolution of the late 1980s and 1990s. That money is what is giving Big Blue the funds to invest in the OpenPower ecosystem – starting with its own Power8, Power8+ and now Power9 platforms and their GPU and FPGA accelerators – here in the 2010s.

In the period ending in December last year, which was the first full quarter that IBM was shipping the new System z14 mainframes, which were announced last June, revenues for the System z platform were up 71 percent and MIPS shipments grew in the double digits, according to Jim Kavanaugh, IBM’s new chief financial officer.

The Power platform, which had a small injection of sales as the initial nodes of the “Summit” supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and its companion “Sierra” system at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory started shipping. In the quarter, Power Systems sales rose by 15 percent, with double digit growth for both high-end NUMA machines, often running SAP HANA’s in-memory database, and low-end machines, often running Linux and open source database or data analytics tools. For all of 2017, according to Cavanaugh, Linux represented a quarter of revenues on Power Systems, up significantly from a few percentage points a few years back. IBM wants Linux to drive Power, and for GPUs and FPGAs to help, which is why it has put so much effort into CAPI, OpenCAPI, and NUMALink interconnects for the Power9 processors. IBM’s storage revenues, which are based on Power hardware and which does not include the storage software such as Spectrum Scale (formerly known as GPFS) and other software add-ons, rose by 8 percent in the quarter. All-flash array sales were up in the double digits, but IBM did not clarify. (As it often doesn’t.)

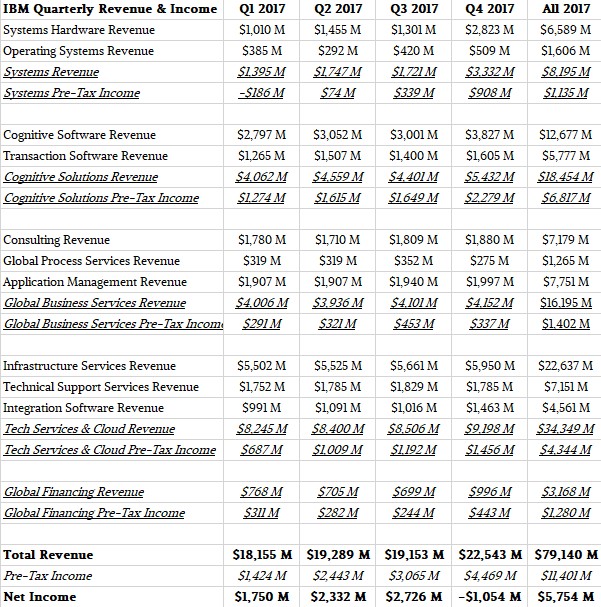

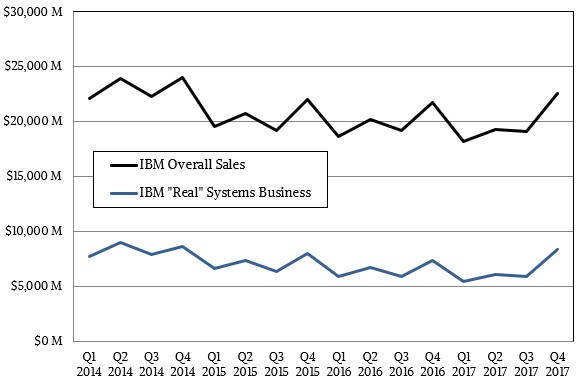

Add it all up, and IBM’s overall systems hardware revenue to external customers was $3.33 billion, with another $179 million sold to other IBM units for their own products based on this hardware. Doing the math based on some figures IBM gives out, we reckon that IBM had $2.82 billion in hardware sales plus another $509 million in operating system sales, with the combination yielding gross profits of $1.87 billion and yielding a pre-tax income for Systems group of $908 million. That is 35 percent growth for hardware against flat operating system sales.

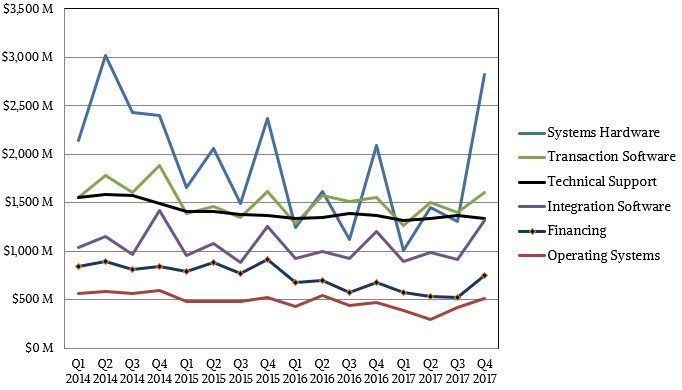

This, of course, is not the entirety of the real systems business at IBM, which is obfuscated by the frankly bizarre way that IBM talks about itself to Wall Street so it can look like it is more of a cloud, mobile, security, and data analytics (cognitive) company than it is. IBM does all of these things, to be sure. To calculate the “real” systems sales each quarter, we take all of IBM’s systems hardware, operating system, and transaction software sales, plus 90 percent of its integration software, 75 percent of its technical support and financial revenues, and then add it all up. This is imprecise, we realize, but if IBM actually talked about itself in a way that made sense, we would not have to make estimates but just observations.

In the fourth quarter of 2017, this number came to $8.34 billion, up 13.3 percent from the year ago period. This represented 37 percent of IBM’s total revenues of $22.54 billion, which is back in a range where it belongs. We estimate that the gross profits for this “real” systems business at Big Blue came in at $4.91 billion, up nearly 9 percent, but still a healthy gross margin at 58.9 percent of revenues and, importantly, representing 45.2 percent of the company’s overall gross profits of $10.86 billion in the quarter.

As we have said many times, this “real” systems business may be a smaller than it once was, but it is still quite large and it is now in upgrade cycles that will give Big Blue some fuel to invest and expand its market.

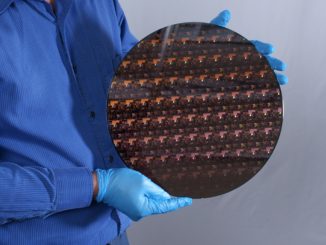

The question now is what the Power9 ramp will look like, and if IBM will see more uptake of these platforms among enterprises and hyperscalers than it did with the Power8 and Power8+ platforms it has sold for the past four years. IBM has been vague about its specific rollout plan for Power9 gear. The first Power9 machine – the “Witherspoon” or sometimes called “Newell” system used in Summit and Sierra supercomputers based on the “Nimbus” variant of the Power9 chip – was commercially rolled out in early December. (We told you about some early competitive analysis on the Newell system a few weeks later.)

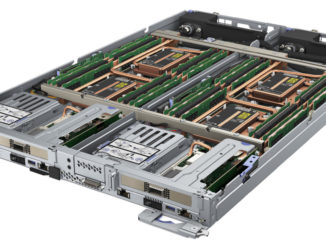

The word on the street is some lower-end iron using the Nimbus Power9 chips will be coming out in March, with variants aimed at Linux-only HPC and data analytics workloads and Nutanix hyperconverged storage coming later, followed by larger four-way systems. Then, later in the year, we expect for the “Fleetwood” high-end NUMA machines, which scale up to 16 sockets in a single system image, to debut. You can bet that IBM wants to get these big iron boxes into the field to see another fourth quarter revenue bump in 2018, when the System z14 upgrade cycle will be spinning slower. In the meantime, more than 9,000 very hefty, GPU-laden nodes will be going into Oak Ridge and Lawrence Livermore over the next two quarters, and more will be sold to customers who want to build baby AI supercomputers using the AC922 Newell systems.

One final note. IBM’s revenue of $22.54 billion was up 4 percent, the first time in 22 quarters that it has seen a revenue decline, but the company reported a net loss of just over $1 billion. Pre-tax income was down 10.4 percent to $4.47 billion, so net income was going to go south in the quarter because of higher sales, general, and administrative costs and lower intellectual property revenues. But IBM was going to be in the black. Then, in the wake of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that passed in Congress in December, which includes a favorable tax rate on profits parked in overseas business units and the re-evaluation of deferred tax assets and liabilities, IBM booked a $5.5 billion charge now for what it expects to come down the pike this year. While there has been much hemming and hawing about how American corporations pay high taxes (nominal rates are around 30 percent of net income) compared to companies located in other countries, Big Blue’s full year tax rate was 12 percent, and then with other writeoffs and changes, it wiggled it down to 7 percent for the full year. The average corporate tax in America is more like 15 percent. So Big Blue clearly has some very good tax accountants. That’s another reason it can keep investing in hardware, we suppose.

Be the first to comment