It has been nearly four decades since the Chinese Academy of Sciences handed Liu Chuanzhi and Danny Lui $25,000 to help found Legend, originally a maker of TV sets that, in the wake of the success of the IBM PC and the Apple II computer, decided maybe becoming a maker of PCs was a better idea.

And it has been thirty years since Legend, which was eventually renamed Lenovo, tipped its PCs on their side and helped create the X86 server market as we know it. It has been 17 years since Lenovo bought the PC business from IBM and eight years since Lenovo bought the Motorola smartphone business from Google and the System x X86 server business from IBM. The latter isolated Big Blue in its System z and Power Systems moats, and has set Lenovo on a course to be one of the largest makers of systems in the world.

As we have pointed out many times, manufacturing systems is a very tough business to make money in. The original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), who make and support iron they sell directly to customers, see margin pressure increase year after year. This is in large part thanks to the direct competitive pressure they feel from each other as well as the indirect pressure they feel from the original design manufacturers (ODMs), who work with hyperscale, cloud builder, and large service provider customers to design bespoke equipment and make it on the cheap.

Having an enterprise customer base is a real asset because there are still some profits there, and that is why Hewlett Packard Enterprise and Dell have focused down on the enterprise and have left Lenovo and its Chinese rival, Inspur, to duke it out with each other and with the ODMs that feed the hyperscalers and cloud builders – namely, Foxconn, Inventec, Quanta, WiWynn, and Celestica are the big ones. Mind you, there are not a lot of profits there. And in the case of Lenovo, which still has a fairly large server business in North America and Europe thanks to the IBM System x acquisition, the company has whatever profits it can glean from enterprises to help prop up its hyperscale and cloud builder aspirations.

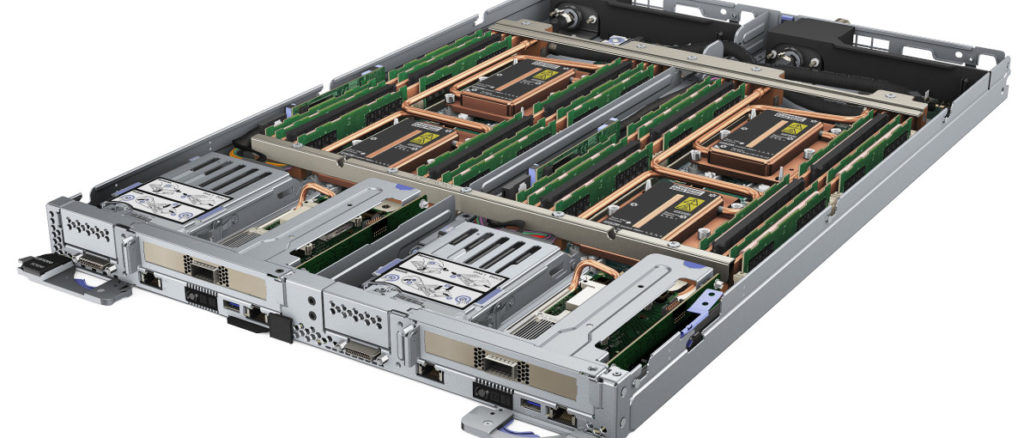

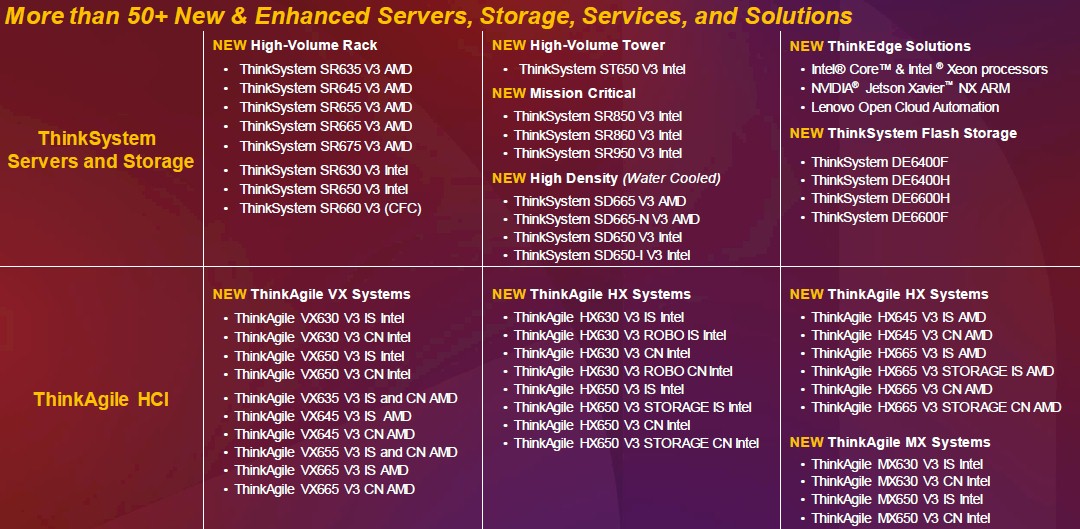

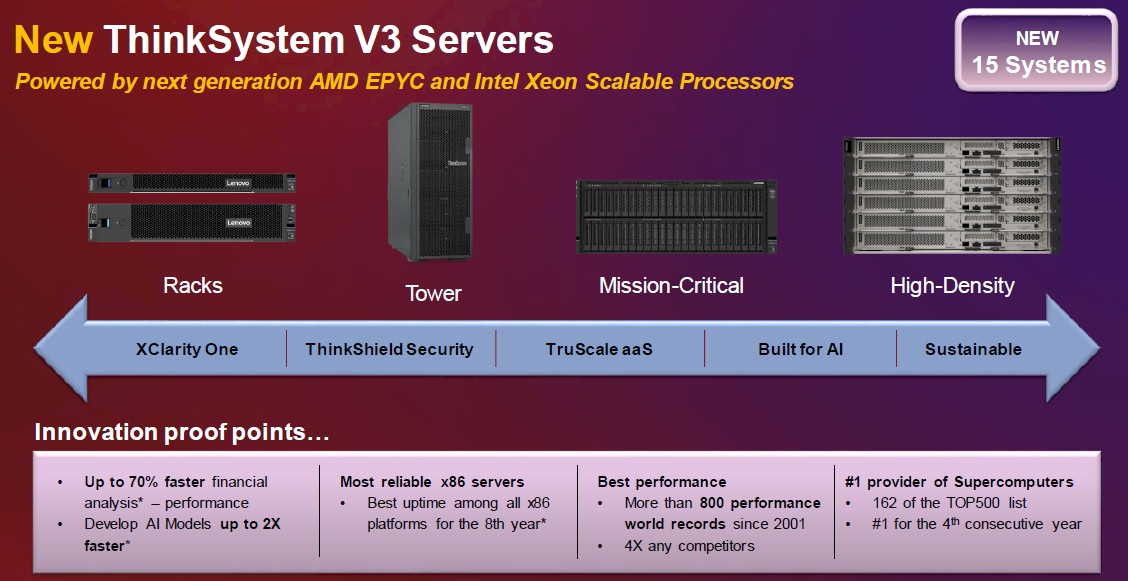

The 30th anniversary server launch last week, Lenovo previewed its future ThinkServer machines that will support the future Intel “Sapphire Rapids” Xeon SP CPUs and the future AMD “Genoa” and “Bergamo” Epyc 7004 processors. We didn’t get any feeds and speeds that are useful, but we did get a sense of the breadth and depth of the Lenovo product line for servers and storage servers, the latter driving software-defined storage across various architectures including converged infrastructure for enterprise datacenters and parallel file systems for HPC and AI workloads.

These sort of “big bang” announcements, where vendors just hurl everything at customers and the media all at once, are increasingly the norm because companies don’t want to spend money launching products continuously. This is cheaper, and every server maker on the planet is constantly pinching pennies, making sure people reuse paperclips, turn out office lights when they are unoccupied, and keep the factories humming as efficiently as possible when the world’s supply chains have gone a little nuts.

Suffice it to say that Lenovo took on 6,500 IBM System x employees and a portfolio of products and patents, and it has managed to maintain an ever-broadening portfolio of systems and systems software. Frankly, Lenovo has done a better job being International Business Machines than Big Blue itself did. The machinery Lenovo sells in the datacenter looks like IBM designs, and the way people talk about it still sounds like IBMers. The difference is that Lenovo is committed to the market, for the longest of hauls, in a way that Big Blue just was not a decade or more ago.

We think IBM made a mistake selling off its PC business, and made another mistake selling off its X86 server business, and Lenovo has been able to capitalize on those mistakes. In 2013, within eight years of buying the IBM PC business, Lenovo took over as the dominant shipper of PCs worldwide; it had become the largest supplier of PCs in China many years before. And the client device business Lenovo has amassed and expanded is profitable, thanks in large part to the company’s vertical manufacturing.

And here we are, eight years into the System x acquisition, and Lenovo has just broken through its first $2 billion quarter and is actually posting some operating income after bleeding red ink for a long time – much as it did in the PC business a decade earlier and as it was doing in the mobile phone business for a long time, too.

It is natural enough to wonder what Lenovo has that IBM ran out of and never had? The first thing is patience, and the second thing is a progressively lower cost manufacturing operation that comes from being a vertically integrated manufacturer across a wide variety of computing devices.

While taking a briefing on the Lenovo product launches, we asked Kamran Amini, a 17-year IBM veteran who is vice president and generation manager of server, storage, and software-defined solutions for Lenovo’s Infrastructure Solutions Group. Amini was a manager of IBM’s BladeCenter blade server development, and was in charge of Flex System converged system infrastructure when Lenovo bought the System x business. In 2016, when Lenovo brought in Kirk Skaugen, who used to run Intel’s Data Center Group, to run its own Data Center Group, Amini was put in charge of both the server and storage businesses at Lenovo underneath Skaugen.

“Growth wise, we have been on a tear in our server and storage businesses,” Amini tells The Next Platform. “Edge has been one of the fastest growing parts of the business, and TruScale as a service has been growing. And we’re growing all of this, and in every region of the world – not just one area. We are serving the top cloud guys with custom designs. We have eight of the top ten hyperscalers as customers. And we are serving all customers – the enterprise, SMBs, MSPs, and system integrators – with our general purpose solutions, which we are expanding with this announcement. I was there for 25 years at IBM and Lenovo together for this 30 year celebration. I believe that IBM, at its core, knew how to drive innovation. A lot of times IBM was the first to market, but just didn’t know how to market well enough and others copied.”

$5 Billion In One Year, With Profits

When Lenovo shelled out $2.3 billion in January 2014 to buy the System x business, it had a relatively small server business and was utterly dwarfed by the like of HPE and Dell, which is now the dominant shipper and revenue generator by far and considerably ahead of HPE, which was neck-and-neck at the time. Inspur, partially due to its reseller agreement with IBM for Power Systems in China (a market that IBM was essentially driven out of, as it would have been with X86 servers, too, had it not sold to Lenovo) and partially due to sales of minimalist machines into Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent, quickly jumped out ahead of Lenovo to become the number three seller of servers worldwide.

In the wake of the System x deal, Lenovo had a simple goal: create a $5 billion-a-year datacenter infrastructure business that generated more profits than its PC business. In theory, neither of these should have been all that hard, given the razor-thin margins of the PC business. In practice, servers and PCs are both tough businesses.

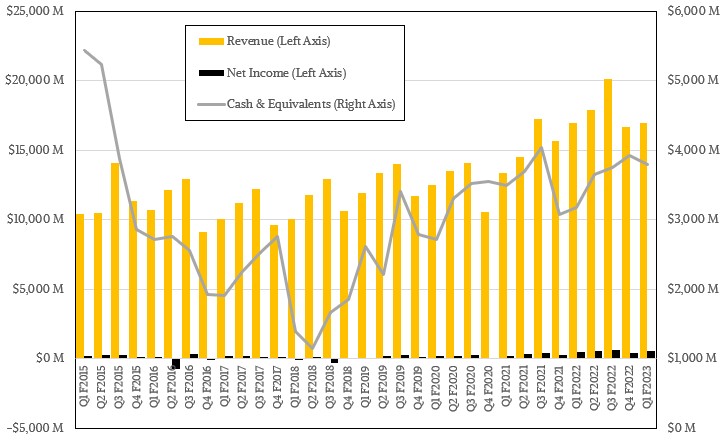

In the first quarter of quarter 2023 just ended on August 10, Lenovo had $16.96 billion in sales, up a small fraction of a percent from the year ago period. Net income, however, was up 10.7 percent to $516 million, but only represented 3 percent of overall revenues. Lenovo’s cash hoard rose by 19.3 percent to $3.79 billion, and that is thanks to steady plodding, quarter by quarter, growing the business and keeping costs under tight control.

The Infrastructure Solutions Group – what used to be called the Data Center Group – took a lot longer than a year to break $5 billion in sales, and it has never come close to matching the profitability – for sure in an absolute dollar sense and not even in a share of revenue sense – as the Intelligent Devices Group business that makes PCs, tablets, and smartphones. In fact, it is hard to imagine that it will be able to ever reach that goal with so many server deals with hyperscalers and cloud builders.

The good news for Lenovo system customers (and the company’s shareholders) is that the client business is subsidizing the server and storage business, giving Lenovo time to figure out how to grow it and get more profits from it.

Lenovo did not break through $5 billion in annual datacenter sales until its fiscal 2019, which was four years after the deal was done. In fiscal 2018, Lenovo’s datacenter business had sales of $4.4 billion and an operating loss of $425 million. While Lenovo grew sales to just over $6 billion in fiscal 2019, it still had a 231 million operating loss that year. When the coronavirus pandemic hit, manufacturing and supply chain issues pushed sales down 8.7 percent and the operating loss was steady at $227 million. In fiscal 2021, sales were up 14.6 percent to $6.3 billion, and operating losses declined by 42.3 percent to $131 million, so everything started moving in the right direction. And kept doing so. In fiscal 2022, ended in May of this year, ISG revenues rose by 13.3 percent and the company posted a 7 million operating profit. It’s not a lot of black ink, but it is something.

Just to give you a sense of how far from that profitability goal Lenovo is for systems, the Intelligent Devices Group had $62.311 billion in sales in fiscal 2022, up 17.6 percent, and an operating profit of $4.74 billion, up 26.4 percent. The client business is bringing 7.6 percent of revenues to the bottom line, and the datacenter business is bringing one-tenth of a percent. The gap between the two is enormous, an seems insurmountable. But it also seemed unlikely that Lenovo could knock Dell and HPE out of their top spots in the PC business, too.

Over the longest of hauls, there are twice as many people in China as there are in the United States and the European Union added together. As the Chinese economy grows and its people gain access to modern technologies, it stands to reason that Chinese cloud providers and enterprises will be similarly huge. Over the long haul. Yes, HPE has a deal with H3C. So what? Inspur is actually indigenous, and the Chinese government wants them to be in business. Lenovo is based in Hong Kong, which provides some level of separation from the Chinese mainland, but not with China being its largest market and the Chinese hyperscalers and smaller Web and cloud companies being important to its business.

That cloud business is a choppy one, and so is the enterprise server business part of the Infrastructure Solutions Group:

There is definitely a rhythm to it in the recent quarters where Lenovo has provided a breakdown of sales between clouds and enterprises. We gleaned this from published charts and estimated the revenues for each category. Lenovo has not provided these figures directly – just like IBM never did for its server lines, now that we think on it.

Lenovo is playing a very long game, and it has aspirations to be the dominant supplier of servers in the world. That may seem crazy, with HPE’s core systems business at around $5 billion or so a quarter, and Dell running at just shy of $10 billion a quarter. Inspur is the one to beat now, which is possible, on the way to catch HPE and then Dell, which seems improbable. We shall see.

Lenovo – absolutely the worst company I have ever dealt with for service and communication. Still waiting for someone to contact me to explain why I had a SECOND order cancelled, even though they have two email addresses and a phone number for me. Shocking lack of courtesy and professionalism.