It is the job of the chief financial officer and the rest of the top brass of every public company in the world to present the financial results of their firms in the best possible light every thirteen weeks when the numbers are compiled and presented to Wall Street for grading. Money is how we all keep score, and how we decide we will invest and therefore live in our old age, hopefully with a certain amount of peace.

Starting this year, IBM has been presenting its financial results in a new format, which helps it emphasize its cognitive computing and cloud businesses. IBM uses those terms pretty generously – a flat file database running on a mainframe is a cognitive solution, for instance, which is funny if you think about how close it is to semi-structured data that is coming to dominate data processing. As we have complained in the past, the new categorization by Big Blue obfuscates as much as it illuminates, and that is why we spend some time each quarter picking apart the figures and trying to reassemble what IBM’s underlying systems business looks like and how healthy it is – or is not.

The good news is that IBM actually breaks its systems hardware (meaning servers and storage arrays with a smattering of switches that it resells) and its related operating systems software businesses out separately with the new categorization of its financial results. In the third quarter ended in September, IBM sold $1.56 billion in its System z and Power Systems servers as well as its various storage arrays to external customers and another $176 million worth of gear to other IBM divisions that create more complete stacks based on the IBM hardware. Those figures include operating systems, too.

That is down by half from when Big Blue still had its System x X86-based server business, which it sold off to Lenovo Group two years ago not so much because this business was unprofitable (as it claimed, which if you looked carefully it was not) but because it was going to get unprofitable as intense competition and volume economics pushed down margins to laser sharp, razor thin bits of cash. IBM may have been the number three peddler of X86 iron in the world two years ago, but Dell had a big lead and IBM was never going to catch up without radically changing the company and possibly acquiring one of the ODMs in Asia or Supermicro, its server partner for the SoftLayer cloud. (That would not have been the stupidest thing IBM ever did, but it did not do that.)

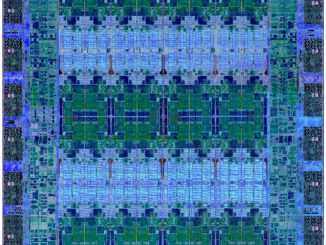

Rather than go wide with the X86 server business, IBM has instead gone deep with its Power Systems business and the OpenPower Foundation that it seeks to cultivate as an alternative to X86 machinery in the datacenter. And by X86 machinery, we really mean Intel Xeon machinery because AMD Opterons don’t really sell, although there is a good chance we could see them enter the field late next year for the Epic Battle Of Datacenter Processing that is brewing. The OpenPower Consortium is getting some traction, and Martin Schroeter, IBM’s chief financial officer, said on a call with Wall Street analysts that “one of the world’s largest Internet providers based in China” had chosen Power-based systems for its hyperscale datacenters. He did not elaborate on who this was, how many systems them have, and whether they were using IBM’s Power8 chips or those made by Suzhou PowerCore, which is now calling itself PowerCore Technology and which has created its own SP1 variant of the Power8.

IBM wants and needs to make money with its own Power Systems iron, which is why it has been contracting out its manufacturing to Tyan and Wistron with its first generation of Power Systems LC Linux-only boxes and has added Supermicro with its second generation of the Power Systems LC iron. The Linux-based Power machines include regular Power Systems, which do not have some of the discounts on processors and memory available on the Linux-only machines that make them more competitive with X86-based systems running Linux, as well as the Power Systems LC setups, and together these now represent 15 percent of revenues for the Power Systems business and grew by “double digits” in the third quarter. That is up from a nominal point or two before IBM got serious with OpenPower three years ago, and that was after more than a decade of shipping Linux on its Power and System z mainframe machinery. Linux has been a huge success on the IBM mainframe – the relative low cost of the software and IBM’s aggressive pricing on the hardware running it basically saved the System z business from oblivion – and IBM is trying to pull off that trick again on the Power Systems line.

Schroeter said that IBM’s margins for its biggest NUMA-based Power iron, which is called the Power Systems scale-out models and which have from four to sixteen sockets in a single system image, held up well in the third quarter, but that margins in the midrange of the line (machines with one, two, or four sockets) were down, and that overall margins for Power Systems were down.

While IBM still sells Power iron running AIX and IBM i, the Power8 machines that support these two IBM operating systems are looking a little long in the tooth at two and a half years old, and customers know that entry and midrange Power9 machines are coming next year. The System z13 generation of mainframes has pretty much had its run, after being in the market for seven quarters, and while IBM has not said anything, it stands to reason that a z14 processor complex will be announced next year around the same time that the Power9 chip is shipping. In both cases, Power and z customers who can wait are gonna wait, or demand very steep discounts on current iron to make up for the price/performance improvements that are coming with the future Power9 and z14 machines. IBM is very enthusiastic about using Blockchain in commercial transaction processing settings, and has 40 clients testing it out on mainframes, but this workload will take a long time to grow. Presumably, IBM will also push Blockchain on Power as well.

We wonder how much IBM is taking in licensing Power technology through the OpenPower Consortium, and similarly wonder how IBM will be keeping track of the revenue in the Power ecosystem as it grows outside of its walls. ARM Holdings has the same problem when talking about the uptake of ARM server chips in the datacenter from its half dozen server partners.

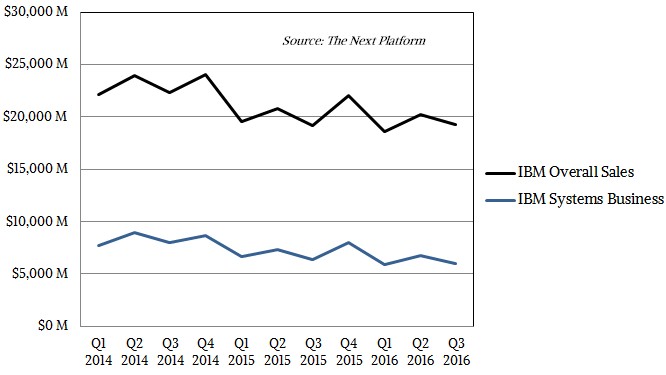

IBM’s operating system business is on the wane, following down hardware sales, and we estimate that Big Blue had $434 million in OS revenues in Q3. The good news is that this part of the IBM systems business is very profitable, with gross profits of $385 million, or 88.3 percent of revenues. The systems hardware business brought in $1.2 billion, and had gross profits of $440 million, 36.9 percent of revenues. The systems business overall had gross profits of $891 million and pre-tax income fell to $136 million. That is a 45 percent decline, and it looks like that Systems business took some cost hits for taxes and other charges. IBM’s overall revenues of $19.23 billion were off a smidgen compared to last year, gross profits were off 4.5 percent to just over $9 billion, and pre-tax income was down 11.2 percent to $3.9 billion. So, like we said, the IBM Systems group took a hit.

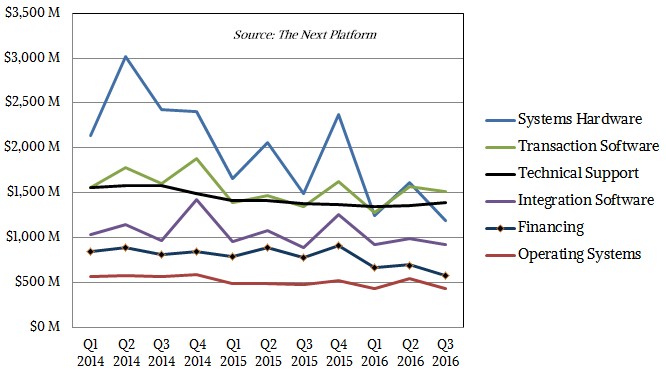

But this is not the “real” IBM systems business, as we have pointed out before. IBM sells integration and transaction processing software for its machinery that drives around $2.5 billion a quarter in Q2 and Q3 and that is very profitable. On top of this, IBM gets various software and hardware support fees, and also makes a good living as a bank financing the installation of its wares through its Global Financing arm. We allocate all of the transaction processing software, 90 percent of the integration software, and 75 percent of the tech support revenues streams to IBM’s homegrown systems business, and when you add it all up, it looks like this:

In the third quarter, that works out to $1.63 billion servers, storage and operating systems (and probably a few hundred million dollars in storage software like Spectrum/GPFS that don’t get counted here), plus $1,57 billion in transaction processing software (CICS transaction monitors and such), $924 in integration software (think WebSphere in its many forms), $1.39 billion in tech support, and $573 million in financing. Add it all up, and it is a tad over $6 billion, and down 11.9 percent from the year-ago period, but still comprising 31.3 percent of Big Blue’s overall revenues. The real systems business is still a big part of what Big Blue does, and if you wanted to be honest about it, all of the higher level services and cloud and application software and databases it sells are also part of a systems business, too.

But you will never hear IBM talk about it that way. Some days, it is like IBM forgot that it is International Business Machines. . . .

Be the first to comment