Two years ago, when Big Blue put a stake through the heart of its impartial attitude about the X86 server business, it was also putting a stake in the ground for its Power systems business.

IBM bet that it could make more money selling Power machinery to its existing customer base and while at the same time expanding it out to hyperscalers like Google through the OpenPower Foundation while at the same time gradually building out a companion public cloud offering of Power machinery on its SoftLayer cloud and through partners like Rackspace Hosting. This is a big bet, and not one that will necessarily pay off for the company, but it sure is a lot more interesting than Big Blue selling off the Power server division to Hitachi or Lenovo or someone else.

For that bet to truly pay off, IBM needs to have hybrid infrastructure that is available in private datacenters that looks and feels like that in public clouds. But as Microsoft’s own experience with the Azure Stack private version of the Azure public cloud shows, it is not so easy to scale down a public cloud to even a size that large enterprises can use economically. And the public cloud has a whole new metaphor and interface for computing, which is different from the barely orchestrated server virtualization that still prevails in the enterprise.

Like other platform providers that are trying to bridge the gap between public and private, IBM has to build that bridge from two sides at the same time and somehow get them to meet in the middle. This is a tough feat, but ants can pull it off and IBM, Microsoft, and others who control their platforms should be able to as well, given enough time and patience from customers to see how the Power Systems in the private datacenter will align with OpenPower systems in the cloud.

This week, with a high-end Power8 server lineup that includes machines preconfigured as private clouds and links to Power capacity running on SoftLayer, IBM is taking an important step forward in delivering the true hybrid cloud capability that its enterprise customers crave, helping those customers feel comfortable about staying on Power iron into the future and moving them towards a new way of managing infrastructure at a higher level of abstraction than what they are used to. But don’t be confused. The new Power Systems E-class C models that Big Blue announced at its Edge conference in Las Vegas are not just chips off the Power-based servers that IBM has been adding to the SoftLayer cloud in the past year.

“This is desirable, and we have been out talking to clients for a little over a month now to get feedback from them and to build this offering in an agile way,” Steve Sibley, director of worldwide product management for IBM’s Power Systems line, tells The Next Platform. “This is one of the primary requirements, but customers have not told us that without that, they won’t start. In fact, over 70 percent of the customers that we talked to about this hybrid offering told us it was relevant to them and it would accelerate their move to Power8 systems. But no question, customers do say that they want to move AIX and IBM i to the cloud and back in addition to Linux. Even though the full software stack is not the same – it is PowerVM on Power Systems and PowerKVM on SoftLayer running only Linux – you can move Linux workloads that you develop out on SoftLayer down onto PowerVM in the datacenter. It is all just Linux. But what we see more often is that customers will develop an application out there on Power Linux – maybe connecting back to a DB2 or Oracle database back in the datacenter – and keep it there.”

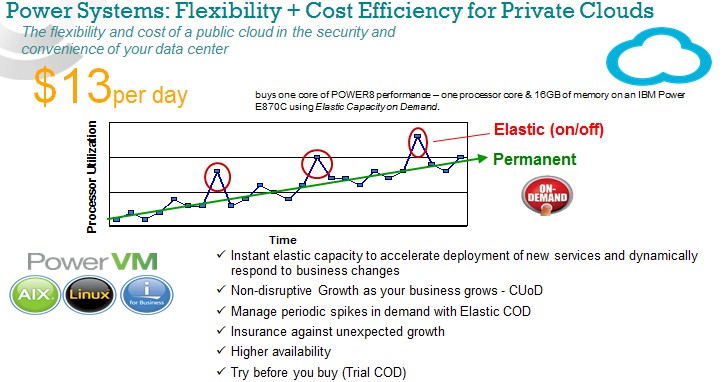

At the moment, IBM’s positioning for Power-based hybrid clouds has customers using midrange and high-end NUMA systems based on the Power8 processors in their own datacenters, which come with elastic capacity that allows customers to processing capacity and memory on a daily basis as well as leases that provide capacity on a monthly basis. The three new cloud machines include the Power E870C and Power E880C, which are based on IBM’s eight-socket and sixteen-socket NUMA boxes called the Power Systems E870 and Power Systems E880. We detailed these two big iron boxes back in May 2015, and IBM enhanced them with larger memory footprints and more powerful Power8 chips in January this year. In October, IBM is expected to offer a Power E850C variant that is based on its four-socket Power8 system, the Power Systems E850, which debuted in May 2015 and which, if history is any guide, will get a memory and processor bump with the Power E850C since these machines were not enhanced back in January.

Under normal circumstances, IBM would have debuted a Power8+ processor this year, perhaps with slightly higher clock speeds and performance and definitely with lower prices. Having not done that – even after saying it would – IBM is using the advent of the C-styled Power machines as a good excuse to cut prices. With the lowering of CPU and memory activation costs on the systems as well as lower prices on Linux, AIX, and IBM i licenses on the C-style systems, the C machines cost somewhere between 10 percent and 20 percent less than the regular Power E850, E870, and E880 systems, says Sibley.

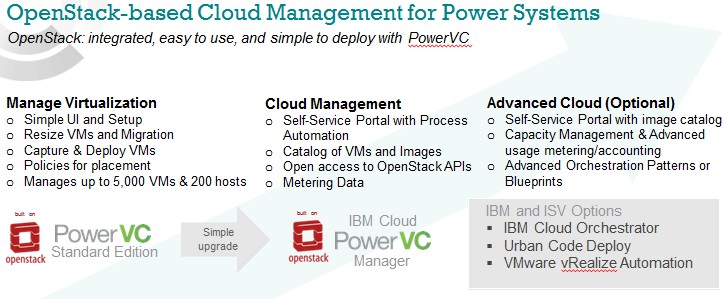

The C at the end of the name of these new systems stands for cloud, obviously, and these boxes come equipped with IBM’s variant of the OpenStack cloud controller, called PowerVC, as well as being supported by the OpenStack implementation that is embedded in Ubuntu Server by Canonical.

IBM’s enterprise customers for Power Systems tend to buy the biggest boxes possible and then use the logical partitioning enabled by its homegrown PowerVM hypervisor to carve up the boxes. IBM has special cores that are tweaked to only allow Linux to run on them called Integrated Facilities for Linux, or IFLs, on this big iron, and they have 75 percent lower CPU core and memory capacity activation costs compared to cores that are allowed to run AIX or IBM i in addition to Linux. This is a big price break, just to show you how serious IBM is about Linux on big Power iron.

IBM’s enterprise customers for Power Systems tend to buy the biggest boxes possible and then use the logical partitioning enabled by its homegrown PowerVM hypervisor to carve up the boxes. IBM has special cores that are tweaked to only allow Linux to run on them called Integrated Facilities for Linux, or IFLs, on this big iron, and they have 75 percent lower CPU core and memory capacity activation costs compared to cores that are allowed to run AIX or IBM i in addition to Linux. This is a big price break, just to show you how serious IBM is about Linux on big Power iron.

In addition to this lower-cost capacity, which brings the cost of a NUMA machine a lot closer to the cost of a cluster of Xeon machines, IBM also allows for licenses to cores and memory activations to be migrated around a cluster of machines – what it calls a Power Enterprise Pool. When you layer OpenStack on top of this – IBM’s PowerVC variant to be specific – and its PowerVM hypervisor and its Live Partition Mobility live migration, you get what is in essence a big iron cloud. In this case, it is one that can scale up to 200 nodes with as many as 5,000 VMs, and IBM’s PowerHA clustering tools can do failover disaster recovery for logical partitions on the cloud, too.

The elastic pricing on capacity that IBM offers is not something you can get with VMware ESXi/vSphere or Microsoft Hyper-V or Red Hat OpenStack or even CloudForms. You can possibly get a full lease on a stack of hardware and software from a server vendor or its banker, but IBM Global Services is a bank in its own right and can offer a full lease on this and the Power Systems division has the ability to charge metered pricing directly to customers for cores and memory without resorting to a complex lease. Sibley says that IBM has hundreds of customers who are using it throughout the workloads running on their Power Systems iron “as a matter of course” with many more who use it for occasional processing spikes. But with the pooling of capacity and the ability to live migrate partitions as well as core and memory capacity around a cluster of machines, more and more customers are looking at elastic hardware pricing.

This is not something that Intel and its hardware and operating system partners offer, and incidentally, it is not something Big Blue offers on its entry Power Systems machines, either.

Just using capacity on demand pricing for cores and memory (rather than an operational lease on a stack), IBM says that it can deliver a Power8 core running at 4 GHz on a Power E870C system with 16 GB of capacity for $13 a day. Investing in a base system is like buying reserved capacity and using the elastic capacity on demand pricing for cores normally inactive in the system is like buying spot capacity on a public cloud.

Customers who buy one of the C-style machines will get a full year of use of a mid-sized Power8 C812L-M single-socket server, which is code-named “Habanero” inside of IBM and which is made by ODM Wistron. (This is sold in the IBM catalog as the Power System S812LC, and it is not one of the new Linux-only machine made by Supermicro that will eventually, says Sibley, make its way onto the SoftLayer cloud.) SoftLayer added the Habanero machines to selected datacenters back in May, and this particular machine that is being given to Power C-style private cloud builders has ten cores running at 3.49 GHz with 256 GB of main memory and two 4 TB disk drives. It costs $1,626 per month to run apps on this bare metal machine, which can be configured with the PowerKVM variant of the KVM hypervisor that IBM has cooked up for the Power8 chips. That works out to a value of just under $20,000, which is cool, but it ain’t much against the cost of one of these big NUMA systems, which can run hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars fully configured. But, there are advantages to NUMA systems and enterprises pay the premium because they can run really big jobs or lots of really small jobs on the same boxes.

Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud Platform, and Microsoft Azure can’t do that, and the wonder as far as we are concerned is why IBM doesn’t have some of these C-style NUMA machines in the SoftLayer cloud proper. Instead, IBM will back up big iron through its disaster recovery services, which are another part of its Global Services behemoth, distinct from SoftLayer.

At the moment, IBM is offering geographically dispersed resiliency, or GDR, for customers who want to automate recovery operations with PowerVM logical partitions within their own datacenters. Starting next year, says Sibley, IBM will extend this out to its own disaster recovery centers as well as to third party partners who provide such services. The GDR software works with AIX, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, SUSE Linux Enterprise Server, and Canonical Ubuntu Server guests, and in the first half of next year will support IBM i. EMC storage (well, Dell storage now) will be supported for this replication, but over time IBM will add support for its own disk arrays.

The Power E870C and E880C will be available starting September 29, with the Power E850C coming later in October. IBM will eventually offer upgrades from prior generations of Power7+ NUMA machines to these cloudy Power8 boxes, probably in the first quarter of next year but the date has not been set as yet.

Be the first to comment