Making the transition from disk storage to flash and other non-volatile media is perhaps more difficult for the makers of storage than it is for customers.

All things being equal, storage suppliers would have preferred for disks to continue selling and flash to be incremental revenue, but IT shops have long been buying at least some of their disk spindles for performance, not for capacity, so it is not surprising that a chunk of storage in the datacenter has moved to flash and that more will migrate as flash gets denser and cheaper and the electronics and software to deal with wear and other factors gets even better than it already is.

The transition from disk to flash does not just is not just involve media, but also is being shaped by new protocols, such as NVM-Express, and new form factors and interfaces, such as the M.2 variant of the SATA interface. The M.2 form factor is interesting in that it allows, in theory, for greater storage density inside of a system, and that is one reason why many hyperscalers have been using M.2 flash memory sticks as boot or scratch devices for a number of years. Microsoft’s Open Cloud Server, the design of which was contributed to the Open Compute Project, has an M.2 flash memory slot, the Apollo r2600 from Hewlett Packard Enterprise can hold a pair of M.2 sticks, and the future “Zaius” OpenPower server being designed by Google and Rackspace Hosting based on IBM’s Power9 processor will have a single M.2 stick.

The density of M.2 devices continues to rise, and is now kissing the 2 TB barrier that allows them to be primary storage in systems.

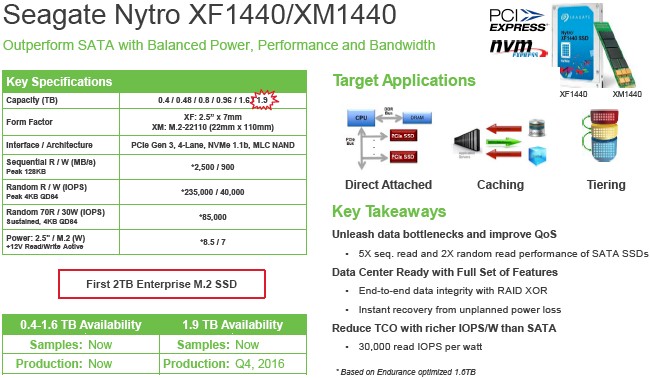

We got to thinking about this because Seagate Technologies, one of the three remaining disk drive makers in the world and now a player in enterprise-grade flash storage, has introduced a new M.2 flash stick. The Nytro XM1140 is a sibling to a 2.5-inch flash drive that Seagate has also debuted; it also competes with enterprise-grade M.2 memory sticks that Micron Technology announced back in April. The Micron M.2 devices range in capacities of 400 GB to 960 GB, the top capacity of Seagate’s previous M.2 devices. Starting in November, when the XM1440 M.2 sticks start shipping, Seagate will double that up to 1.92 TB.

This is not as easy as it sounds. All of the enterprise-grade flash drives that Seagate ships have power loss data protection, which means they have enough capacitors on them to hold enough juice to get data in flight stored onto flash cells when a system loses memory. Cramming the capacitors and memory for this into a 2.5-inch drive form factor is tricky, and compressing it down to an M.2 device is even harder.

The M.2 device standard is a follow-on to the mini-SATA interface and it uses the PCI-Express Mini Card layout and supports PCI-Express (with NVM-Express or not) as well as SATA protocols for linking devices to systems; it is commonly used for external storage in consumer devices but is being increasingly adopted for storage inside of servers. The Micron and Seagate M.2 devices announced above both support NVM-Express protocols and links back to the PCI-Express controllers commonly on processors these days, and that means they have very low latency data transfers to and from the flash.

“The feedback that we get from customers that are deploying these systems is that they are looking for the smallest possible footprint, so the more compact you can get, the better,” Kent Smith, senior director of product marketing at Seagate, tells The Next Platform. “If you can get more flash into that 2.5-inch form factor, then that is good. But the more flash you get behind the controller, the more you are controller limited. So if you are trying to optimize the configuration, getting a combination of the greatest number of controllers and the highest amount of flash. You try to do the two at once, and the best way to do that, to get the best ratio, is the M.2 form factor. And that also gives you the advantage of having a much smaller form factor footprint so that when you design the servers, you just need the PCI-Express bus. So for drive count, you can actually go up to pretty significant numbers, not like SATA which limits the number of drives on the bus.”

Smith has caught wind of a storage server design that will cram 60 M.2 ports into a single 2U server chassis, for a raw capacity of 120 TB using the new XM1440 M.2 drives from Seagate. (We are trying to locate this machine, which was on display at the Flash Memory Summit this week.)

This density is made possible given that the M.2 flash stick has about a third the area and a little less thickness than the 2.5-inch flash drive, which is encased in metal like a disk drive and is meant to be hot pluggable like one, too.

The XM1440 comes in endurance optimized versions that have 400 GB and 800 GB sizes and capacity optimized versions that come in 480 GB, 960 GB, and 1.92 TB sizes. Pricing was not announced, unfortunately.

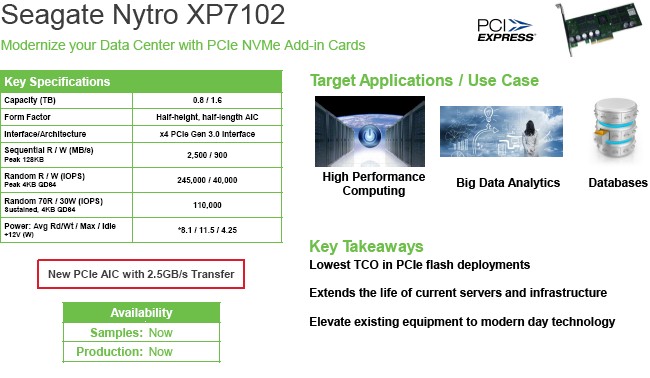

Not every server maker has M.2 form factor sockets on their system boards, so Seagate has to offer the same basic functionality in a PCI-Express peripheral card form factor, and that is what the Nytro XP7102 is all about. Here are the feeds and speeds:

The Nytro XP7102 card has the same 2 TB of raw capacity as the 2.5-inch and M.2 devices above, but it has some of its capacity overprovisioned to allow for it to have higher write performance.

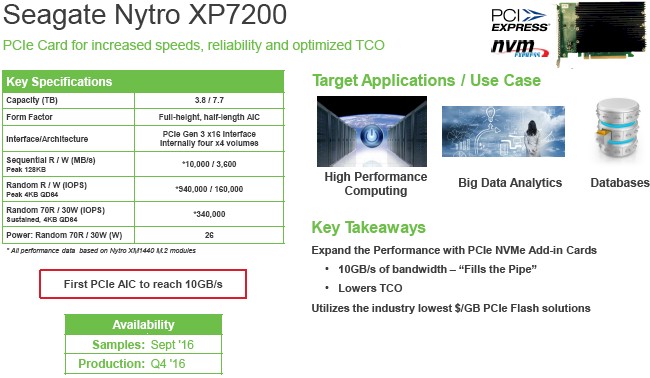

For those needing a little more oomph from a PCI-Express card, and wanting to fill the PCI-Express pipe with 10 GB/sec of sustained bandwidth in and out of the flash, Seagate has debuted the Nytro XP7200 card, which will start sampling in September and ship in the fourth quarter.

The Nytro XP7200 is actually four of the M.2 cards welded onto a single PCI-Express card, topping out at a raw capacity of 8 TB and becoming the first card, according to Smith, that can hit that 10 GB/sec sequential read bandwidth rate.

“We can have four different controllers on the XP7200 card, and we don’t have to have a PCI-Express bridge or any other aggregation point and we actually bifurcate the ports to the host so that it actually can talk to all four M.2 controllers at the same time,” explains Smith. “You are almost at the full speed of the PCI-Express bus that that point getting that 10 GB/sec. And you are just shy of 1 million IOPS on a single plug in card.”

For The Clouds

Seagate exited the enterprise SATA market two years ago, but with the Nytro XF1230, the company is re-entering this space to chase the market for cheaper cloud storage. The SATA interface runs at 6 Gb/sec on this device, which is a lot slower than those above, but presumably the cost per unit of capacity is very low; the active power on this flash drive is also about half that of the ones above, which is also significant for those building very large arrays. With a sequential read bandwidth of 550 MB/sec and sequential write bandwidth of 500 MB/sec, though, this is not a very high performance device; ditto for the 98,000 random read and 17,000 random write I/O operations per second for the Nytro XF1230. But for cloud storage, web serving, tiered storage analytics, and other read intensive environments, cost per capacity and power draw are key metrics that are just as important as raw performance.

The Nytro XF1230 comes in a 2.5-inch form factor and in capacities of 240 GB, 480 GB, 960 GB, and 1.92 TB. Smith says that it only burns around 26 watts doing random reads and writes, compared to something on the order of 50 watts to 60 watts for competitive cards from Intel, SanDisk, and PMC Sierra. This is a card that will be particularly appealing to certain HPC, data analytics, and database workloads where capacity, compactness, and performance all matter. (Then again, we wonder that a server with four M.2 slots could not accomplish the same performance, and perhaps at a similar to lower price.)

For the fattest flash in the Seagate portfolio, and something that is clearly designed to stream untold millions of cat videos, Seagate is showing off a future and yet unnamed 60 TB flash drive. This monster drive will have a flashback to a 3.5-inch form factor, and given that size it will have 1,280 2D NAND flash chips from Micron jammed inside of it. With a mere 17 drives, users will be able to build a storage array with over 1 PB of flash storage and require far fewer controller interfaces than an array using 2.5-inch SSDs that, from Seagate at least, top out at 16 TB these days. The active power on this 60 TB drive is around 15 watts, and it has two 12 GB/sec SAS interfaces to keep it linked to its controller at reasonably high bandwidth. This drive is not going to be a speed demon on writes (stats were not available), but will be able to do around 150,000 IOPS on random reads (that’s 4 KB file sizes) and handle about 1.5 GB/sec on sequential reads and 1 GB/sec on sequential writes using 128 KB file sizes. The features of this drive are being determined now by hyperscalers, cloud builders, and server OEMs right now, says Smith, and production will happen sometime in 2017 depending on the feedback.

Just imagine a Supermicro SuperStorage Server 6048R with 90 of the 3.5-inch bays crammed with these in a 4U space, weighing in at 5.4 PB. Ten of these and you can have 54 PB of all flash in a single rack. Heaven only knows what it would cost, since Seagate does not provide manufacturer’s suggest retail pricing or any other kind of pricing. This means real customers have to wait for OEMs and ODMs to get prices before they can have input and make server architecture decisions, unlike the lucky few hyperscalers and cloud builders and OEMs that get insight into technology and pricing at the same time, and well ahead of the market.

Neutral Territory

Seagate is not only a kind of Switzerland of flash, given that it does not make its own flash but rather sources it from many others, and Smith says that this is a key differentiator for the company. Those who make their own flash chips and sell their own flash devices would argue, of course, that this is what gives them a strategic advantage. . . .

Seagate is also keeping its eye on 3D XPoint, and has a relationship with Micron for 3D XPoint as it has for flash and they have built drives together in the labs based on 3D XPoint. So there is an expectation that Seagate will have access to and eventually sell 3D XPoint as well as 3D NAND flash devices.

Be the first to comment