Big Blue does not participate in any meaningful sense in the booming market for infrastructure for the massive hyperscale and public cloud buildout that is transforming the face of the IT business. But the company is still a bellwether for computing at large enterprises, and its efforts to – once again – transform itself to address the very different needs that companies have compared to a decade or two ago are fascinating to contemplate.

In a very real way, the manner that IBM talks about its own business these days, which is very different from how it described the rising and falling of its revenues and profits across its vast conglomerate, is a reflection of how it sees the future of business computing, particularly among the Global 2000 customers who now, after many divestitures in the past decade, represent the lion’s share of its revenue stream. It is as much a forward looking statement, using the language of Wall Street, as it is a measure of current performance in its own business.

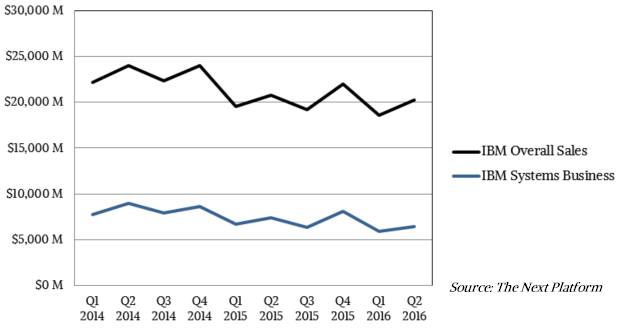

On the whole, IBM’s top line revenues have been dropping steadily for a very long time, even with acquisitions and adjusting the businesses to take out the effects of divestitures, and in the second quarter of 2016, the overall trend continued, with revenues dropping 2.8 percent to $20.24 billion and net income down 27.4 percent to $2.5 billion. While IBM’s chief financial officer, Martin Schroeter, can and did declare that Big Blue was ahead of many of its goals in terms of transforming its business from supplying a wide variety of servers and systems software to supplying more infrastructure and applications over its SoftLayer cloud, the IBM that many of us remember after its near-death experience in the early 1990s – the one that consistently had single digit revenue growth and double digit profit growth once it righted itself a few years later during the dot-com boom – is long gone. The thing about IBM – and now Microsoft – is that you can’t count it out so easily. Both companies could find better footing and both have vast customer bases that can reinvigorate them. That said, VMware, which sells software to make virtual machines on X86 iron, is about a third the size of Big Blue and arguably has at least one or maybe closer to two orders of magnitude more active customers.

As we pointed out back in April when IBM announced its new financial reporting categories, the company does not make it easy to see its underlying and very large platform business, which consists of servers, storage, operating systems, various kinds of middleware and systems management tools, and databases and analytics tools. IBM wants to be able to show that its cognitive tools and cloud products are growing fast, and it lumps a lot of what is arguably legacy systems technology into the mix to pump up these categories as well as its more broad “strategic initiatives.”

Starting this year, elements of IBM’s former Software Group and Global Services sub-businesses – the former driving a large part of its profits and the latter driving a lot of its revenues – have been carved out and put into new units. The largest of these new operating units is called the Technical Services and Cloud Platform group, which has a wide variety of infrastructure and technical support services (including the SoftLayer public cloud) as well as IBM’s WebSphere middleware and its Bluemix implementation of the Cloud Foundry platform cloud stack, and other integration software. This is the largest group within Big Blue now, but that distinction is largely arbitrary.

In the second quarter, the Technical Services and Cloud Platform group accounted for $8.86 billion in sales, down a half point and shrinking a lot less than the company overall, but significantly, pre-tax income for this group was off 9.6 percent to $1.28 billion. Within this group, integration software (including WebSphere middleware) comprised $1.1 billion in sales, down 8 percent, and Global Technology Services, a very broad category of stuff, made up $7.8 billion in revenues, up 1 point.

IBM has lumped all of its database, transaction monitoring, and analytics software into a new group called Cognitive Solutions. In the first quarter, this group had $4.68 billion in sales, up 3.5 percent year on year, and significantly gross profits in this area, thanks to very high margins on IBM’s mainframe software, were still at 82.2 percent. Ditto for the integration software in the Technical Services and Cloud Platform group, which had gross margins of 85.3 percent in the quarter because of the very high prices that IBM can charge on its mainframe platform.

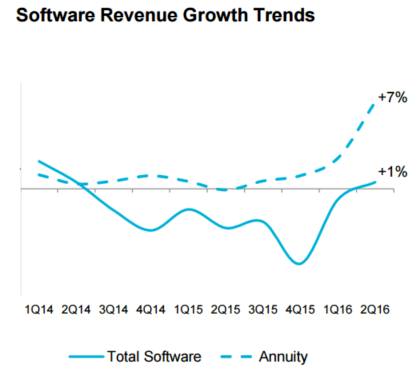

If you don’t think that IBM understands the concept of a platform, you are wrong. It all started with the System/360 mainframe, the first modern computing platform from five decades ago. The irony is that IBM seems to have forgotten how to talk about what it does and what it believes, and that companies like Microsoft, Amazon Web Services, and Oracle took Big Blue’s historical platform precedents to heart and are building similar platforms. The tough news for IBM is that its pre-tax margins in this part of the business are under pressure. The Cognitive Solutions group sold another $594 million in wares to other IBM units in the quarter, for a combined revenue of $5.27 billion, up 4.7 percent. But pre-tax income across external and internal revenues fell by a stunning 20.5 percent in the quarter. Some of this is just a shift from perpetual license to subscription sales (usually over a cloud) for various software – a transition that all software companies are wrestling with but which, truth be told, are a return to the old ways of IBM from the 1960s and 1970s when everyone rented rather than bought software.

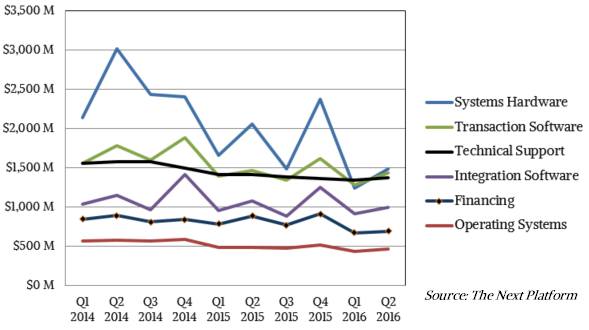

The underpinning of any platform is, of course, hardware. IBM’s hardware business is now very cyclical because it no longer has the steady stream of sales from the X86 server business that the company sold to Lenovo in October 2014. With the System z13 and Power8 server platforms both at the end of their product cycles, revenues are predictably down. IBM sold $1.95 billion in systems in the second quarter, down 23.3 percent, and including sales to other IBM groups, the Systems group had $2.16 billion in sales, off 21 percent, and pre-tax income fell by 57.4 percent to $229 million. This is not a margin level that IBM is comfortable with, and while it Schroeter did not discuss this, the company is no doubt investing heavily in the next-generation z14 and Power9 processors as well as coming to the end of the z13 and Power8 product cycles.

System z revenues were off 40 percent in the second quarter, and Power-based servers had a 24 percent decline as sales at both the high-end and the low-end of the Power Systems product line slumped; midrange systems saw a spike, but the revenue jump was not enough to fill in the gap. Significantly, Linux-based systems accounted for 10 percent of Power Systems sales in the quarter, and Schroeter said on a call with Wall Street analysts going over the numbers that IBM would be leveraging technologies from the OpenPower ecosystem to shortly bring two new Power8-based machines to market aimed at analytics workloads, and added that the next-generation Power8 machine aimed at HPC workloads and employing NVLink interconnects on the Power8 chip for lashing Nvidia Tesla GPU coprocessors very tightly to Power8 chips was also coming to market. Nvidia has said not to expect systems from Cray, IBM, and others using the “Pascal” GP100 GPUs to be launched until later this year for shipment early next year, so it is not likely that Big Blue will see much of a revenue bump for this machine in 2016.

Storage revenues have been a drag on IBM for quite some time, and were off 13 percent in the second quarter. Predictably, disk-based products were off and flash-based products could not fill in the gap. This is a pattern that we have seen across the storage market.

Operating systems are still a reasonably big business for Big Blue and are a key part of its Systems group. In the second quarter, IBM sold $500 million in operating systems, down 4 percent, with the bulk of that being for monthly rentals for its mainframe platforms. The wonder is why IBM does not shift to monthly rentals for its AIX and IBM i platforms.

We are always interested in looking at IBM’s numbers to try to figure out how its “real” platforms business is doing, and if you add up systems hardware, operating systems, transaction software, integration software, technical support, and financing, this gives you a pretty good proxy for that. (In our model, we allocate 90 percent of IBM’s integration software revenues and 75 percent of its technical support and financing revenues to its own System z and Power Systems platforms.) If you do that, then in the second quarter IBM’s overall platforms business was down 12.6 percent to $6.45 billion.

There are bright spots in the IBM numbers, although you have to dig for them. The company’s cloud revenues, including the SoftLayer public cloud and the revenues IBM derives from helping companies build private clouds, was up 30 percent to $3.4 billion in the second quarter and the company’s annualized run rate for infrastructure, platform, and software services sold under a subscription basis hit $6.7 billion in the quarter. But that is still a tiny amount compared to the $85 billion or so IBM will rake in during 2016.

IBM has a long way to go before it can convert the Power Systems business into a platform that has the financial momentum of the System z business, but it is clear that the company will need to do that over the long haul if it still wants to be a platform provider.

We are skeptical that IBM – or anyone else for that matter – can build a modern platform that can be this profitable. But we know IBM has to try, and then build the applications on top of that that will yield real profits and an annuity revenue stream that is growing and predictable. As the chart above shows, the company is making some progress here. And most ironic of all, not making much money in hardware systems might just turn out to be table stakes for having a very profitable systems software and application software business in the 21st century for Big Blue.

Be the first to comment