Being in business for over 100 years is an accomplishment, and IBM has made more than a few jarring transitions in its long history, having started out as a supplier of meat slicers, scales, time keeping, and punch card tabulating machines. The company is undergoing yet another massive transition, and the global economy and the strength of the US dollar relative to other currencies in countries where Big Blue does a lot of its business are not helping.

In the third quarter, the contrast between the old and the new was once again pronounced, and the piece parts, transactional businesses that IBM has traditionally depended on for a large portion of its sales slowed across its systems, software, and services businesses and The Next Platform and cloud businesses that IBM has invested heavily in over the past few years did not grow fast enough to fill in the gap.

Martin Schroeter, IBM’s chief financial officer, explained the company’s strategy to Wall Street analysts in going over the financial results for the third quarter ended in September. “Our approach is to integrate acquired content with our own organic capabilities, and leverage partnerships and a broader ecosystem to build new high value platforms, like Watson, SoftLayer, Bluemix, and OpenPower,” Schroeter said. “This is a longer-term play. We are creating new platforms, and building ecosystems, and much of this is an ‘as-a-Service’ model. We are continuing to invest at a high level as we shift our spending to our strategic imperatives.”

That said, Schroeter conceded that IBM missed its revenue targets for the third quarter, and laid the blame on its slowing sales of high-end disk storage arrays and that a transformation in its Global Business Services unit, which is staffing up to sell and support these new platforms, is taking longer than expected. There are plenty of other headwinds that IBM faced in the quarter, too, and some of them are macroeconomic, not just a shift away from buying best-of-breed components and toward buying platforms for creating new kinds of applications.

The company’s revenues fell by 13.9 percent to $19.28 billion, but 9 points of that decline was due to currency effects and 2 points was due to the offloading of the System x business to Lenovo. Gross profits in the quarter fell by 13.2 percent to $9.44 billion, but because IBM had writeoffs relating to the sale of its System x and chip businesses in the year-ago period, the $2.95 billion in net income was a lot better than the $18 million it posted in Q3 2014.

IBM’s sales in the US fell by 4 percent, and across the Americas region, sales were down 3 percent to $9.1 billion in the third quarter (that is a constant currency growth rate). IBM’s revenues in EMEA rose by 1 percent to $6.1 billion, and Asia/Pacific fell by 1 percent to $4.1 billion, again at constant currency. In the several dozen “growth markets” that have been traditional drivers of its systems and services sales in years past, revenues again were off, in this case by 3 percent in the third quarter, and sales in the formerly exploding Brazil, Russia, India, China (BRIC) countries, IBM’s revenues were off 7 percent at constant currency. The BRICs were down 18 percent in the second quarter, so the situation is somewhat improved, but in this quarter sales in China were down 17 percent and in Russia were off in the single digits; India was up in the double digits, and Brazil was up 4 percent against a tough compare. Japan and Germany had strong growth in the third quarter, and sales in the United Kingdom, France, and Canada improved, too.

IBM’s cloud revenues, which are spread across its various operating groups, include revenues from its SoftLayer public cloud as well as virtualized and orchestrated systems that it sets up on premises for customers plus various software that IBM makes available on its public cloud or those on premises private clouds. For example, IBM’s Bluemix implementation of the Cloud Foundry platform cloud has only been available on SoftLayer, but IBM has just made it available for private clouds. Add all of these cloudy infrastructure, platform, and software services together and IBM says this business has an annualized run rate of $9.4 billion as the third quarter ended, and through the three quarters of 2015, Schroeter said cloud revenues rose by 65 percent. The IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS parts of that $9.4 billion in revenue came to $4.5 billion, which seems to imply that private cloud revenues have an annual run rate of $4.9 billion. But IBM did not elaborate on a breakdown between private, hybrid, and public cloud spending by its customers or discuss how much of its server, storage, and software revenues were driven by private clouds.

Schroeter added that the acquisitions of StrongLoop, experts in the Node.js programming language, and Cleversafe, an object storage vendor, were primarily done to bolster its cloudy offerings. He also said that SoftLayer, which sits within its Integrated Technology Services division of the Global Services behemoth, had double digit revenue growth in the quarter, but did not say what that revenue might be.

SoftLayer is now operating 28 of its own datacenters, and if you do the math, those facilities have the capacity to host 335,500 servers. That does not mean, however, that SoftLayer has that many machines. As of the summer of 2014, SoftLayer had around 120,000 machines and had plans to roughly double that number as it spent $1.2 billion to build out the SoftLayer cloud globally. The company has traditionally added around 20,000 machines a year, but that was back when it had only 13 datacenters a year and a half ago. SoftLayer could have anywhere between 175,000 and 200,000 servers by now, we estimate.

IBM has kept on Supermicro as the supplier of machines for SoftLayer, maintaining a relationship that stretches back to the hoster’s founding a decade ago. It will be interesting to see how aggressively SoftLayer embraces IBM’s own OpenPower systems, like the Linux-based Power Systems LC machines made by Tyan and Wistron that were announced by Big Blue two weeks ago and that it believes can offer competitive advantages against Xeon iron.

While IBM is investing heavily in its platforms, it still has a sizable and profitable systems business, and its mainframe and Power Systems are platforms in their own right and the foundation of some of the higher-level platforms that Schroeter is referring to. (IBM’s Watson and Watson Health analytics runs on Power-based systems inside its SoftLayer cloud, for instance.) You have to peel apart IBM’s revenues in each of its groups and divisions to get a sense of that systems business – something IBM itself should do if it wanted to show what a large systems business it still has even after selling off its X86 server business last October.

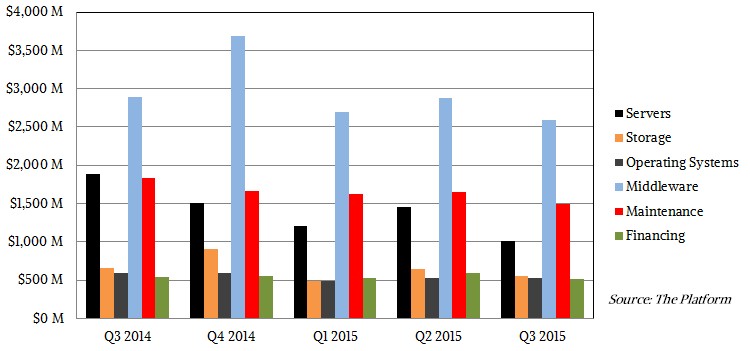

Here is what IBM’s real systems business looks like, as far as we can tell:

In the third quarter, we reckon that IBM pushed over $1 billion in systems and $548 million in storage. As its server business has contracted, its operating system business has also shrunk (since it was a big reseller of Windows and Linux on X86 iron), and Schroeter said on the call that even after the divesture’s effects were over, Wall Street should expect a 1 percent headwind each quarter for operating systems for the foreseeable future. If you add systems, storage, and operating systems up, that works out to $2.1 billion. At constant currency, IBM’s Power Systems business had 2 percent growth, with growth for its entry Power8 machines aimed at scale out clusters and midrange businesses as well as for the high-end systems that are used by large enterprises as database and ERP software platforms. The System z line, which had a processor update in January, had a 20 percent jump in revenue and a parallel 18 percent bump in total capacity shipped in the third quarter. We think that the z13 upgrade cycle is running a bit faster than past upgrade cycles and perhaps the revenue stream from mainframes will continue to decelerate in the years ahead. That said, this is still a good and profitable business for IBM, and one that is helping to pay for its Power Systems transformation through the OpenPower Foundation.

If you add in middleware that IBM sells on its own systems, plus maintenance and financing for those systems and their related software, then the real IBM systems business came in at about $6.7 billion in revenues in the quarter. That is considerably lower than the $8.4 billion we estimate the real systems business made for IBM in the year ago period, to be sure, but this overall business is still more profitable. That said, it is a little bit of a concern that the underlying systems hardware business – servers plus storage – had a pre-tax operating loss of $24 million in the quarter. That’s better than the $99 million loss in the year ago-period, but IBM wants to keep that number solidly in the black. In the trailing twelve months, IBM’s systems hardware sales (including external sales to customers as well as internal sales to other IBM units) came to just over $8 billion and had a pre-tax operating profit of $643 million.

Putting an final note on the quarter, this is what Schroeter had to say: “When you look at our results through the first three quarters of this year, we have expanded margins on a fairly stable revenue base, while we are reinventing our business. We have maintained high levels of investment as we shift our spending to our strategic imperatives. We are creating new platforms and are building ecosystems including Watson, Watson Health, SoftLayer, and Bluemix. And we have been getting returns on our investments, with growth in the strategic imperatives over 30 percent. At the same time, the core is declining in a declining market as we deliver productivity to our clients so they can reinvest in the new areas. We have always said this takes time. Especially because much of the new content is delivered as a service and our progression wouldn’t be a straight line, but our execution over the sustained period is a proof point that we are on the right path.”

This transition for IBM, we think, is as dramatic as the one that the company did in the mid-1990s as it shifted from what was essentially a collection of warring fiefdoms and independent platforms to a peddler of servers, storage, middleware, and databases aimed at supporting others’ software and backed by system integration expertise. This time around, IBM wants to be the seller of platforms once again, and is in a sense undoing what it has spent two decades building because this is what it believes the market wants. The good news is that this time around, IBM doesn’t have to cut its workforce by a third and take eye-popping writeoffs because it learned from its experience.

Be the first to comment