It is difficult to argue with the fact that Amazon has upset the traditional model of IT as a cost center. By leveraging its investments in both hardware and software over the years to support its retail business, then flipping those over to become what might become a more profitable operation in its Amazon Web Services segment, the company has quite successfully turned risk into an entire cadre of rewards.

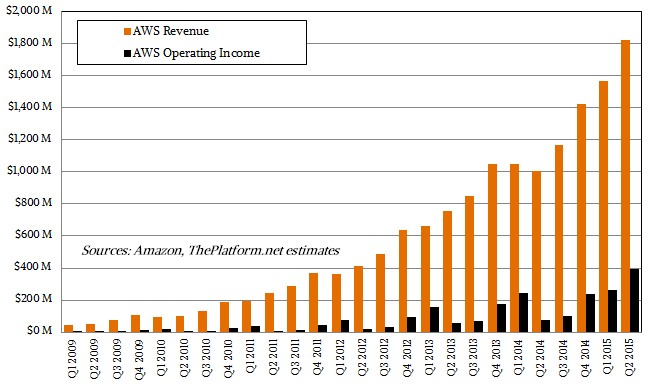

The revenue for the AWS segment is a bit difficult to break out in fine-grained detail, but over the past quarter, revenue for the AWS segment increased 81% to $1.82 billion—a notable uptick, as seen in the chart below. During this same time period, operating income increased 407% to $391 million, a 21.4% operating margin. Even excluding a $71 million favorable impact from foreign exchange (this is a bit mysterious, but could be the result of investments in India and Europe), AWS segment operating income increased 314%.

What is notable here is that all of this growth is on the heels of some significant price cuts of its services, which happened in tandem with a bevy of new services and sites that will come with their own datacenter construction and outfitting costs.

As Amazon chief financial officer, Brian Olsavsky, noted in the company’s quarterly call with investors, “We’ve had multiple price cuts this year. We are now up to 49 since launch in 2006, so it is a fundamental part of our business model. So is innovation. We have over 350 new features and services, also significant features and services that have launched this year.”

Among those new investments are the new generation Intel Haswell processors, news around an entrance into the Indian cloud market, and the opening of the EU region in Frankfurt, Germany, which AWS says is its fastest growing international region to date. The company is also expanding its datacenter footprint, adding new centers around the U.S., some of which are powered by solar and wind—the excess of which can be sold back to the local grids.

So with all of this in mind, how is it possible that the revenue for AWS has jumped so significantly? It’s all about the growing base of users and upticks in the core hours being consumed by existing customers, according to Olsavsky.

When it comes to big iron, few companies on the planet have made investments in hardware over the few years quite like Amazon Web Services. As we have detailed at length here at The Next Platform, the company continues to push the efficiency limits on both the hardware and software side to be not only price-attractive (but not the cheapest), but rich in terms of the storage, network, and application services it can provide.

“We are seeing continued increases in both usage, sequentially and year over year. We are also seeing a great efficiency in the business on a cost basis. Innovation is accelerating, not decelerating. We had over 350 significant new features and services…and while pricing is certainly a factor, we don’t believe it is always the primary factor,” Olsavsky said during the quarterly call for investors.

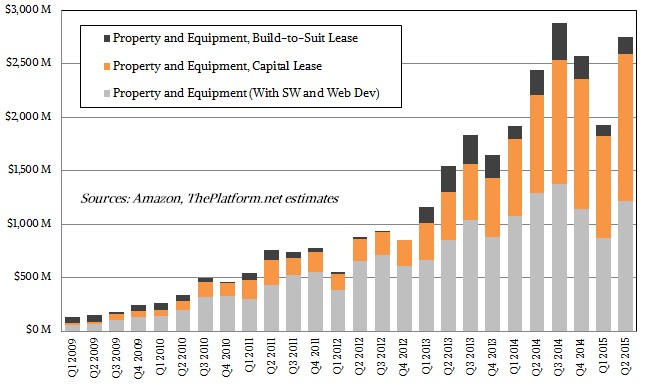

“We do realize it’s a capital-intensive business and we have modeling that shows it’s going to be a very – it is a very good business for us and that’s what we aim for as long-term return on invested capital and free cash flow. So, we’re certainly cognizant of the capital part of the calculation.”

As we reported back in April, most of the Amazon datacenters have somewhere between 50,000 and 80,000 servers. If you do some math on that, you get a server count that ranges from a low of 1.4 million machines (that’s 50,000 machines each with one datacenter in each availability zone) to a high of 5.6 million machines (if you assume 65,000 servers per datacenter and an average of three datacenters per zone).

True to retail fashion, AWS is using the breadth and depth of its cloud computing offering as well as continually lowered pricing to drive its business, and the strategy seems to be working with such high growth in the first quarter. It would be interesting to see precisely how elastic demand is for EC2 compute and S3 and EBS storage services, and only AWS knows for sure because it is the only company with the data about how its customers are behaving. It is also fascinating to ponder how far AWS can push down prices and still drive up usage on its cloud while maintaining – or perhaps even expanding – its profitability. It takes a lot of investment to keep building up the AWS flywheel and keep it spinning, as you can see from Amazon’s overall capital expenditures chart above. No one knows for sure how much of this is allocated to AWS and how much is allocated to the other Amazon business units, but presumably AWS accounts for a large portion of this capital expense.

Thus far, only Google and Microsoft have been able to keep pace with such an investment, and both companies have their own reasons for building infrastructure aside from selling it as a service. We think that the big will keep getting bigger in the public cloud because of the enormous pricing benefits from those who buy in volume, and that means AWS, with such a big lead over its rivals, will continue to attract more customers and drive up usage and therefore the gear it needs to buy for the next wave of expansion. If it took Amazon eight years to get its first million customers, it will probably take half that time or less to get the next million, and its cloud could more than double in size during that time, too.

Call it the Brain to Brawn ratio.