We are still mulling over all of the new HPC-AI supercomputer systems that were announced in recent months before and during the SC25 supercomputing conference in St Louis, particularly how the slew of new machines announced by the HPC national labs will be advancing not just the state of the art, but also pushing down the cost of the FP64 floating point operations that still drives a lot of HPC simulation and modeling work.

Like many of you, we think that the very nature of HPC is changing, and not just because of machine learning and now generative AI, but also through the advent of mixed precision and the ability to change solvers to use it or to use lower-precision math units to emulate FP64 processing. It will be an interesting second half of the decade, to be sure.

In the meantime, given the large amount of FP64 native code out still there, we think it is important to take a long perspective and see how FP64 performance of compute engines is being scaled up as the number of engines continues to be scaled up and out. We also think that the capital investment that machines require is getting to be quite high, but lucky for every HPC center on the world, then, that GenAI is making spending billions of dollars on a supercomputer seem, well, normal.

If you can get them to budget four times the computer because it will be doing GenAI half the time, then you still end up with twice the HPC performance. . . . And you don’t need a supercomputer to do that math.

Anyway.

As we pointed out in a story called Show Me The Money: What Bang For The HPC Buck? way back in 2015, which was when The Next Platform was founded by myself and my lovely wife Nicole, it is a lot easier to build a faster supercomputer than it is to bring the cost of calculations down. And the GenAI boom has made GPU accelerators a lot more expensive than they might otherwise have been and also have scale up networks for GPUs that are akin to the tightly coupled federated interconnects that supercomputer makers like SGI, Cray, and IBM were working on in the mid-1990s that also add significantly to cluster costs.

The bandwidth requirements for scaling out these fat GPU servers into clusters is also enormous, much more intense than days gone by. Scarcity and high demand as well as technical sophistication is driving up the cost of scale, even if the cost per unit of FP64 compute does, in its zigzaggy way, does keep getting smaller.

We have separate comparisons of FP16 and FP4 machinery for AI workloads, so know that in this story we are just focusing on those HPC centers that are still heavily dependent on double precision floating point math. We are aware that solvers are being recast with mixed precision as well as the Ozaki method that allows for FP64 to be emulated with lower-precision INT8 units and boost the overall effective throughput of simulation and modeling applications. That is a story for another day. (And we are working on it, in fact.)

Also, comparisons are meant to be illustrative, not exhaustive. In the 48 years since the Cray 1A vector supercomputer was launched, essentially creating the supercomputing market distinct from mainframe and minicomputing systems that could do math on their CPUs or boost it through auxiliary coprocessors, it has been very difficult to get the cost of systems. Yeah, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose not only about the lack of precise pricing, but also in hybrid architectures for supercomputing, as witnessed in 1989 by the IBM System/3090 with Vector Facilities pitted against a Cray X-MP. This was the first HPC runoff I ever wrote, about at the very beginning of my career as an analyst and a journalist. (I, too, am a hybrid, and always have been, and I have always done enterprise computing and supercomputing and I added hyperscalers and cloud builders and now AI model builders.)

We have always contended that HPC is about performance at any price, and the GenAI boom is, by this definition, certainly a kind of HPC. The clouds and hyperscalers generally optimize for the best price/performance, while regular enterprises, governments, and academic institutions tend to optimize the computing for a set budget. Having said that, the HPC community has been very good about benchmarking the performance of large-scale systems on a wide variety of workloads and making such results available to the public while also making some pricing information available. This is not just data altruism, but rather a reflection of the fact that national and state HPC centers are publicly funded and their budgets are therefore a matter of public record. Moreover, politicians and HPC centers rightfully like to brag about their prowess in building supercomputers – just like hyperscalers and model builders do these days, almost daily it seems.

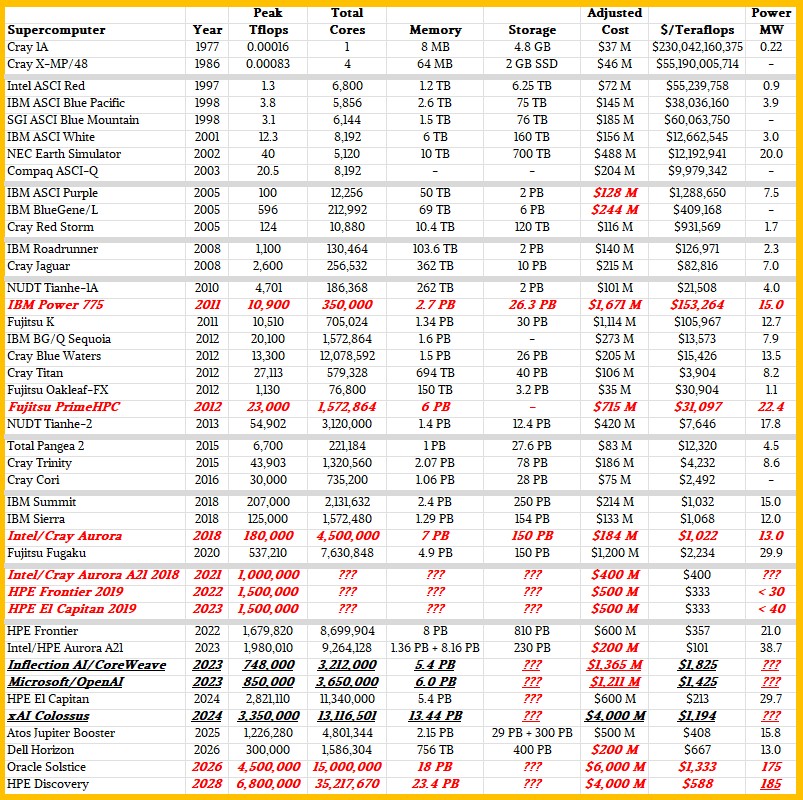

We know these numbers are not perfect, and that every important HPC system that was ever created is not shown. But the machines chosen were all flagship systems in their time, representing both architectural choices and the limits of budgeting in those times. We have adjusted the machine costs of older machines for inflation, which we think is important over long time horizons. Performance in the tables and chart below are peak theoretical teraflops at FP64 precision. We also show the concurrency in the machine – the total number of cores and, these days, streaming multiprocessors or hybrid cores included in GPUs and XPUs. The concurrency has obviously grown by a huge amount as clock speeds stalled 25 years ago and more and more performance is needed in a node and across a system of interconnected nodes.

Admittedly, we could have dug around and filled in more machines from the 1970s, 1980s, and the early 1990s, but decided to use a Cray 1A from 1977 and the Cray X-MP/48 from 1986 to represent the apex of their respective decades. If time was no object, we could do this. But time is always an object. We think it is very interesting to compare everything to the Cray 1A, the touchstone for beauty in supercomputing, and our tables do just that.

So, without further ado, here is a historical comparison of supercomputers with a few AI-focused training systems thrown in for recent years just to turn up the contrast a little:

As usual, data shown in bold red italics is our estimate, and ??? means we are not confident in making a guess (at least not within the time constraints of this article). Also in bold red italics are initial expected configurations for pre-exascale and exascale supercomputers funded by the US Department of Energy. We left in the two interim architectural choices for the “Aurora” system at Argonne National Laboratory, which was originally due in 2018 as a 180 petaflops machine and then in 2021 as a 1 exaflops machine but which came to market as a nearly 2 exaflops machine in 2023 – and with a substantially reduced price as Intel took a $300 million writeoff on the $500 million deal because of the massive delays in getting Aurora into the field. This resulted in a machine that has extremely low cost per FP64 teraflops.

We also put in the expected configuration of the “Blue Waters” Power 775 cluster that IBM was supposed to build for the University of Illinois but pulled the plug because it was going to cost $1.5 billion rather than the $188 billion the National Center for Supercomputing Applications paid for a hybrid CPU-GPU system from Cray that took the Blue Waters name. (Adjusted for inflation, IBM Blue Waters would have cost $1.67 billion, and Cray Blue Waters cost $205 million. IBM was GenAI-class before its time, in so many ways, with the liquid-cooling and intense integration in its Power 775 cluster design.)

The rough configurations of the “Frontier” exascale system at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the “El Capitan” system at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory laid out in 2019 are also kept in here as well as their original budgets. The DOE spent a 20 percent more on these machines, and Frontier was a bit more powerful and El Capitan, installed a year later, had 1.9X more performance. The switch to AMD CPUs and GPUs from IBM CPUs and Nvidia GPUs really drove bang for the buck. Nvidia is back in the HPC game in earnest, and governments the world over are repositioning national HPC labs as sovereign AI datacenters.

We are adding the “Colossus” system from Elon Musk’s xAI company to the list, which has 100,000 of Nvidia’s “Hopper” H100 and H200 GPU accelerators in a single system, as a benchmark for both performance and budget for last year. (Colossus has doubled in size this year, and the total spend for this machine is reportedly around $7 billion, with over 200,000 Nvidia GPUs deployed.)

The four new machines on this list include the GPU booster partition of the “Jupiter” supercomputer at Forschungszentrum Jülich in Germany, the first of what will eventually be many exascale-class machines in Europe. Jupiter was built by the Eviden unit of Atos using Nvidia CPUs and GPUs and is up and running.

We have also added the “Horizon” machine being built by Dell for the Texas Advanced Computing Center and representing the most powerful machine dedicated to academic science in the United States. We know that Horizon’s total budget is $457 million, but that figure includes helping pay Sabey Data Centers to modify a datacenter for HPC use as well as paying for space, power, and cooling as well as the new machine. We think that about $200 million of this was for the Horizon system itself, which is based on CPU partitions using Nvidia’s future “Vera” CV100 Arm server CPUs and GPU partitions based on a pairing of Nvidia’s “Grace” CG100 CPUs and “Blackwell” B200 GPUs.

We also took a stab, based on some very slim information out of the DOE, at what the future “Soltice” system at Argonne and even more future “Discovery” system at Oak Ridge might look like. Oracle is the prime contractor on Solstice, which will have 100,000 of Nvidia’s Blackwell GPUs. Discovery is based on AMD “Venice” Epyc CPUs and “Altair” MI430X GPUs and which, according to HPE and AMD, will deliver somewhere between 3X and 5X the performance of the current Frontier machine. No specific number of Altair GPUs have been given out, so we took a stab at it given the 120 petaflops FP64 performance on the vector engines inside of the MI430X. We have read somewhere that Discovery might cost only $500 million, and that Discovery plus a smaller system called “Lux” based on the “Antares+” MI355X GPUs would cost more than $1 billion.

Both Solstice and its “Equinox” testbed based on 10,000 Blackwell GPUs and Discovery and its Lux testbed acquisitions were not done using normal DOE processes and were described as being part of a “public-private partnership.” By which we think the DOE means it is having the machines commissioned but will be renting some – but certainly not all – of the capacity on these machines. The reason we know this is simple. Our first guess is that Solstice machine costs $6 billion and Discovery will cost $4 billion. That’s $10 billion to buy two machines. The Office of Science budget at the DOE was only $8.24 billion in fiscal 2025. Like OpenAI, the US government cannot afford to buy GenAI-class supercomputers and must rent them, and we think at a premium price compared to owning them. No one is talking specifically about this, but we will keep digging to get better pricing data and to find out who is going to be using the rest of the capacity on these machines if DOE isn’t able to buy all of that capacity.

As you can see, FP64 performance and concurrency have gone way up over the decades, but the cost per teraflops has not come down quite as fast as the price of a capability-class supercomputer keeps rising.

In adjusted 2023 dollars, a Cray 1A cost $36.8 million in 1977 and nine years later in 1986 a Cray X-MP/48 cost $46 million. ASCI Red in 1997 cost $72 million. In 2008, the “Roadrunner” hybrid CPU-accelerator system at Los Alamos National Laboratory, which broke the teraflops barrier, cost $140 million in 2023 dollars and the “Jaguar” system, based on AMD Opteron processors and the XT5 interconnect and also from 2008, cost $215 in relatively current dollars.

For those of you who like a visual, here is a scatter graph that shows performance in teraflops on the X axis and cost per peak system teraflops on the Y axis:

That system that is all the way over to the $100 per teraflops line is Aurora (as delivered) after $300 million is taken out of its $500 million cost.

As you can see, this is a fairly straight line up and to the right, which is what you want to see on a log scale for supercomputer performance increases and the cost per teraflops reductions. There is, however, plenty of variation.

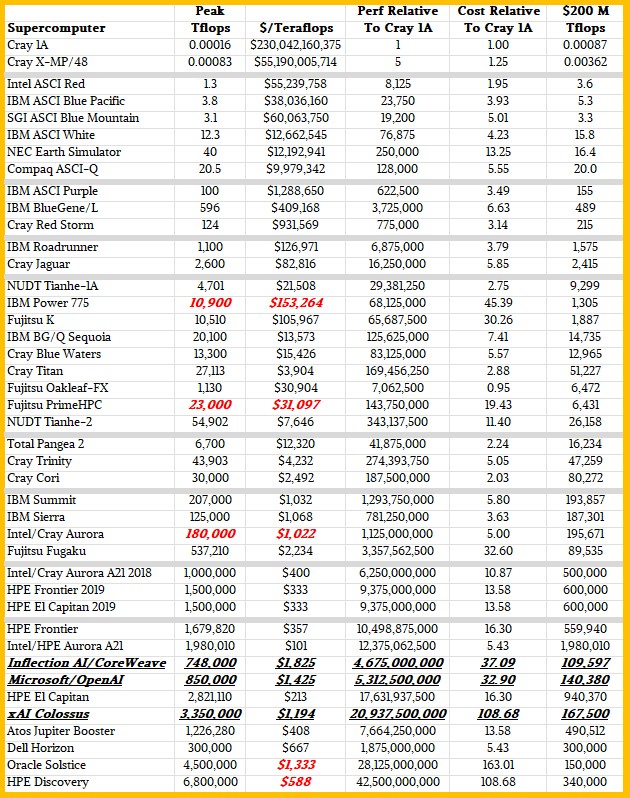

As we said above, it is interesting to compare machines coming next year and beyond to the Cray 1A from five decades ago. Performance difference between the Cray 1A and the Discovery system coming in 2028 to Oak Ridge is a delta of 42.5 billion and concurrency has risen by 35.2 billion. System costs have risen by 108.7X between 1977 and 2028, provided that our estimates for Discovery are in the ballpark.

By the way: Turning these numbers inside out, it would take $230 billion in 1997 to buy 1 teraflops of FP64 compute, and there would be no way to parallelize across the 6.25 million Cray 1A machines it would take to get to 1 teraflops. (Coaxial switches are not going to work. . . . )

To get our brains wrapped around the numbers a little better, we built a second table that shows all of these machines with their performance and bang for the buck and then gauges it against the Cray 1A. This table also shows how many teraflops at FP64 precision $200 million (in 2023 dollars) would get you:

El Capitan set the high bar for this, unless you count the very discounted price of Aurora. Going forward, that $200 million chunk of budget is going to get HPC centers a whole lot less FP64 on the vectors. So, they had better plan on using tensor cores more and getting algorithms working with mixed precision. This will be the only way to keep advancing.

Using linpack flops as the sole metric pulls a few of these systems out of line, and it’s actually important for this discussion: Most of the systems on your list are large clusters of commodity-ish processors with modest memory bandwidth, linked by high-ish speed networks. Several of the price outliers are expensive because they are high bandwidth machines: Earth simulator, Power775, and the old-school crays had orders of magnitude more bandwidth than contemporary systems which made them much more expensive per linpack flop, but much stronger for specific applications.

A couple of the machines are price outliers because they tried to jump out of timeline and deliver a computer several years before the industry trends would bring it to market: Earth simulator, power775, K, Fugaku.

The Newest machines are jumping out of the line for a variety of reasons: They are much higher bandwidth than the Asci machines or Cori. They are expensive because of the global competition for parts. (What would Titan have cost if Cray was selling billions of systems to AI customers?) Lastly, they are jumping out of line because lithography progress is slowing down.

One can imagine the AI bubble bursting, which would reduce the competitive pricing pressure, and might reduce the demand for super high bandwidth interconnect. Both of which would bend linpack flops up a bit. However, lithography is advancing more slowly, and at much greater expense than historical trends. Even AI is unlikely to fix that trend line. Arguably without AI there may not be enough money to drive the fabs forward as fast as they are going, but it’s still not up to the pace of the past.

Good points! I’d eyeball the dollar-performance data from ASCI Blue Pacific to El Capitan as roughly: $/TF ≈ 10⁸ / TF⁰⋅⁹ and we see that Fugaku is about 3x that, but it certainly was an “out of timeline” new-tech outlier that launched ARM into HPC and required development of potent vector units (plus enhanced microarchitecture) which now underpins the Neoverse V line. And looking at HPCG instead of HPL shows the performace-cost of Fugaku dropping to 2x that of Frontier and El Capitan (if I calculated correctly), which is nice.

But for machines relying on GPUs, I’d say we’re not looking so much at new-tech for FP64 HPC these days but rather suffering from an “AI tax” on those units. Colossus, Solstice, and Discovery are 8x to 13x more expensive per FP64 HPL TeraFLOP than the long-term trend. AMD’s idea of an HPC-focused MI430X (vs the AI-focused MI450X) makes more and more sense to me here.

Agreed. Or we run FP64 in emulation and get 2X or 3X effective throughput, so I hear.

True enough. Necessity is the mother of invention, and HPC folks have a track record of successfully subverting available tech (eg. Paul’s commodity HW) to achieve their algebraic ends faster and cheaper, skirting industry surcharges. Foxing graphic-rendering hardware into executing *GEMM in the early 2000s was a great example, as were the earlier Beowulfs that freed HPC labs and Geats from the twin plagues of Grendels and dragons (iiuc).

Emulation though (the word), it must be said, may have remained a bit of a four-letter blasphemic profanity in this circle, ever since that time long ago when 8087 slayed such evil hex for good. An emulation by any other name may be sweet however, I guess, if it works … And with the great memory wall having become what it is, there’s probably room today for algorithms that are more compute intensive (relative to memory access) which could give this tech a few days in the HPCG sun.

Ozaki and MxP sound promising in this respect, if only as stopgap measures, to reconjure the djinn of FP64 oomph out through the low-precision lock-up where it is being confined by industry’s enthusiasm for the opportune promises of a different sort of computational spirit. I’m looking forward to your upcoming writeup on this innovative witchcraft! RIKEN seems to like the idea too ( https://www.nextplatform.com/2025/08/22/nvidia-tapped-to-accelerate-rikens-fugakunext-supercomputer/ )

Any tech that helps us get an $800M FP64 ZettaFlopper by 2039 is welcome in my book ( https://www.nextplatform.com/2024/08/26/bechtolsheim-outlines-scaling-xpu-performance-by-100x-by-2028/ )

Your bigger question is not unique to HPC:

When transistors stop getting cheaper, how will the industry keep making computers faster? Whether that is for HPC, Iot, ERP, Cloud services, or streaming videos – some day the free upgrades will stop; then what?